A Book Review for Times and Seasons of the First Major Biography of Joseph Smith in Twenty Years, Wherein I Demonstrate My Own Longwindedness in Contrast to the Author’s Skillful and Admirable Concision

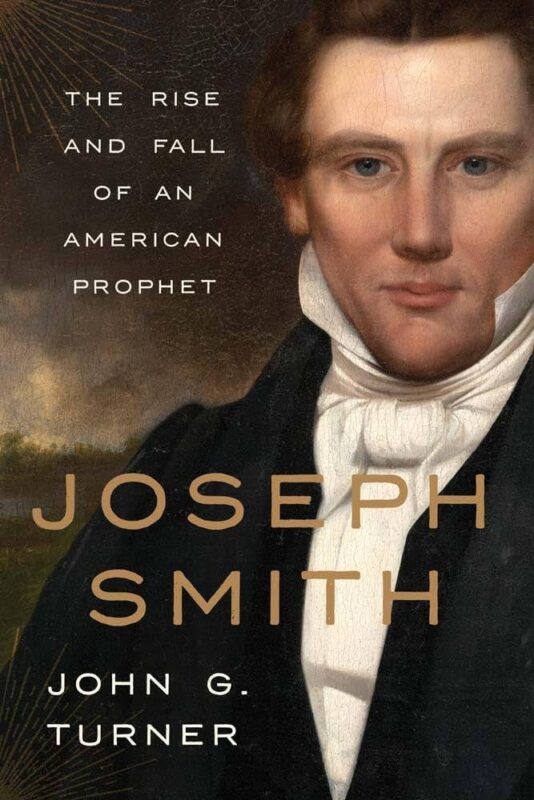

John Turner’s new biography Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet (New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2025) is precisely the sort of book I’ve waited for since my back-to-back readings of Mormon Enigma and Rough Stone Rolling twenty years ago. Unable to restrain myself, the first part of this review will focus on this meta-fact: I think something new and remarkable has been done here. The second half will dive more into the text itself, and I’ll end with two powerful lessons that the book imparted to me.

Part I: My self indulgent reverie on what this book means overall with respect to how we tell our history and understand ourselves as a people:

In 2004 while walking to and from the metro on my daily commute, Avery and Tippetts revealed to me for the first time many of the uncomfortable elements of our history. Bushman’s biography (on the same commute a few months later) put “fire in my bones” for Joseph Smith—a fire that wasn’t exactly extinguished but was decidedly checked by the reaction of my co-workers. As a graduate student I worked in a stuffy, nerdy archive at the Department of State with a group of retired senior diplomats. Our break room table was the stuff of legend, with ongoing debates and a circulation of scholarship and journalism whose intensity put to shame the academic lounges where I spent an equal amount of time. I loved that space and continue to cherish what those colleagues did for me. It was with genuine excitement in this atmosphere that I promoted RSR to these colleagues—and was subsequently stung by the honest and equally unenthusiastic reviews of some of my closest associates, none of whom made it all the way through the tome. “I read Fawn Brodie’s biography of Joseph Smith some years ago. Now there was a compelling biography” I remember one of them telling me.

For most of our history, the Church has maintained an understandable and even sincere policy of exaggeration with regard to how we tell our story. It has also employed obfuscation with regard to our records (which obfuscation, as Turner’s biography makes clear, began with Joseph Smith himself). These two actions by the church have colluded with an ever willing string of patently unfair and dishonest attacks from critics: the Church actively ignored historical difficulties while its antagonists saw nothing but these difficulties—we all know the result of these polemics. So I can’t help but feel an enormous sense of triumph now that Church leadership and its professional historians have made it possible for historians like John Turner to do something very different. I don’t know that Turner fully succeeds in answering Jan Shipps’ call for scholars to get the “prophet puzzle” of Joseph Smith right—and I can’t say for sure what my former diplomat friends would’ve thought of this book (and Turner’s final sentence certainly reads like a grand caveat!). But what he’s written is a remarkably readable, comparatively concise and engaging text that I think handles the “believer-vs-skeptic” polemics well.

Turner is himself a remarkably rare bird—a non-Mormon scholar who has taken seriously our history and culture, and who has from the beginning spoken in a dialect members recognize and understand. (I remember being shocked the first time I read his work, a biography of Brigham Young, at how comfortable he seemed in Mormon-ese and positions, a sentiment reinforced when I met him and heard him pronounce “Lehi” and “Nephi” correctly, to say nothing of the sophisticated level at which he articulated our conventional ideas.)

We’re fortunate as a people for the opportunity that this book gives us to respond to the irruption of the Restoration in a way parallel to Joseph’s family and closest associates—who knew all or many of the details that Turner discloses in a way that Latter-day Saint generations ever since have not. Zion’s Camp really was a sort of bumbling disaster—yet those who marched with Joseph and witnessed firsthand his shortcomings largely stayed with him. Turner is sometimes at a loss to explain this fact, though he doesn’t fail to notice it. There’s tremendous import here for us today. That first generation of Saints should inspire confidence: everyday Saints today can develop just as informed and mature a faith as William Smith, Brigham Young, Eliza Snow and all the others who personally witnessed the real weaknesses and unfulfilled prophecies of Joseph Smith alongside his triumphs.

Without minimizing Turner’s personal professionalism and evident generosity, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say his biography is a result of the Joseph Smith Papers (JSP) project. In addition to praising the JSP, we should praise the cadre of faithful historians in the church (and some who have left us) who for decades now have modeled and embodied honest and open tellings. In addition to professionally developing the historical corpus, these historians have welcomed John into their midst, not to convert him, but as a genuine friend. As Turner makes clear, Joseph’s decision to obscure some of the less glamorous aspects of our history was a genuinely existential calculus. His religious views and activity generated violent conflict from the time he announced his possession of the Golden Plates, and, contra what one might hear over church pulpits or classrooms across the globe on any given Sunday, the United States has not been a land of prodigious liberty and religious tolerance for Latter-day Saints and many other groups. Americans’ willingness to murder and plunder the Saints followed us into our exile. While the 21st century is a far cry from the 19th in this respect, the Church’s pivot to a full and exhaustive disclosure is still a remarkable decision. It enables biographies like this one, and it clearly constrains anyone else writing about Joseph. The JSP and subsequent biographies like Turner’s allows the most ardent critic of Joseph Smith’s excesses to recognize that there’s more to Mormonism—and more to prophetic, revealed religion—than exploitative charlatans and dupes.

The JSP and Turner’s volume also allow the faithful to see a prophet without subscribing to ridiculous fantasies of perfection and without treating adult members’ intelligence as though we are all tender-aged primary children. Joseph himself was uninterested in standing on a pedestal. “Many think a prophet must be a great deal better than anybody else. Suppose I would condescend (yes, I will call it condescend) to be a great deal better than any of you. I would be raised up to the highest heaven, and who should I have to accompany me? I love that man better who swears a stream as long as my arm, and administers to the poor and divides his substance, than the long, smooth-faced hypocrites” (21 May 1843, Words of Joseph Smith).

Perhaps even more importantly, if we as a people can’t genuinely move past the narrative that everyone who dislikes Joseph Smith dislikes him because they’re evil or influenced by the devil, then we’ll never be able to understand our own sincere family members and friends who leave. I can’t say I’ve ever been a fan of William McLellin, and Turner made me like him even less by detailing his actions in Missouri. He also helped me to understand and empathize with why McLellin lost faith in Joseph’s leadership in the first place. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine maintaining our traditional loathing for the Law and Higbee brothers in the wake of Turner’s much clearer telling of Nauvoo history. One can see and believe in an important difference between the likes of Hyrum Smith and the likes of William Law, without demonizing Law.

Decades of dedicated Mormon and non-Mormon historians have dramatically elevated the whole discourse and made way for those of us in the Church to once again approach something like the faith of our well-informed founding generation.

Part II: Where I at least try to be less self-indulgent and offer a more particular review and evaluation of some of the book’s key features:

In addition to praising Turner’s book generally and exulting in my own analysis of the meaning of this biography, I also want to praise some of its particulars. I’ll then speak candidly about a few places it falls short.

I found it as fair and professional a biography as can be written by someone not convinced of Joseph Smith’s claims. It’s well-written and very readable. Following a standard structure, it moves through the by-now familiar key events in Joseph Smith’s life. The chapters are creatively titled and contain helpful context, summaries, and foreshadowing that link key themes.

While the broad outlines are familiar, Turner fills in the story with smaller, delightful—and occasionally disturbing—details. On the delightful side, it’s always great to read new details of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. While I was familiar with the swirling brown-colored seer stone Joseph used and which the Church still possesses, I’d not heard of him using this stone to find a second (and better!) white seer stone (24-25). I’d never heard of Joseph taking Samuel Laurence to the Hill Cumorah during an interim year (36). Both delightful and disturbing are the sprinkling of humanizing details about Martin Harris throughout the text. We all know about Joseph’s enjoyment of physical contests like wrestling, but did you know he wrestled in contests while a prisoner? The entirety of the fall of Far West and the transition to Illinois, including the various escapes, was riveting. It was disturbing to read of participants in the Hawn’s Mill Massacre serving as members of the grand jury reviewing the case against Joseph and the other leaders, and delightful to read third party observers’ accounts of Joseph and his disposition (231). Turner is also good for pleasant and occasionally clever puns (I loved his pairing of “wits and writs” on 319). The chapter on the martyrdom begins with the poignant detail of Joseph’s viewing of Benjamin West’s Death on a Pale Horse (356).

I was particularly impressed with the rich contextualization given to certain revelations from the Doctrine and Covenants, which contextualization allows equally for secular and spiritual interpretation. Most non-Mormon scholars I’ve read are even more dismissive of this book of scripture than they are of the Book of Mormon. Like many of you, I’ve spent this year immersed in the Doctrine & Covenants, and while I’ve enjoyed learning more of the history (Mark Staker’s Hearken O Ye People is fantastic), my reading has been primarily spiritual and theological. Hence, it was great to also get the very particular contexts of these revelations which straightforwardly functioned to consolidate Joseph’s prophetic authority, and to learn of an important initial motivation for publishing the Book of Commandments: as a response to outside critics’ charges concerning Joseph’s secret and nefarious revelations (110). All of these details and the enhanced contextualization make the book engaging, even for those of us who already know the plot by heart.

Some aspects of Joseph’s history will be upsetting for any believer with even an ounce of moral perspective. Personally, I was nauseated by the story of Lucena Elliot (166-167), which was new to me. Polygamy is perhaps chief among the stumbling blocks for anyone who believes in personal morality and social equality. As Turner and others with their eyes wide open have noted, however, it’s hard to pin Joseph down as anything like a straightforward villain when it comes to his multiple marriages (or, alas, as a straightforward messenger from heaven). Consequently, it’s hard not to be impressed with Turner’s straightforward humility on the topic; which, to be clear, he applies to his empirical rather than his theological investigation; the latter is largely absent: “Any historian writing about Joseph’s polygamy has to admit a significant degree of uncertainty, about everything from the number and timing of the marriages to the nature of these relationships” (255). Careful observers might add ‘origin’ and ‘meaning’ to the list of uncertainties.

There’s likewise, an overall humanity to the book. Turner skillfully and empathetically paints both Joseph and his enemies (in- and outside of the church), without failing to capture the horror of what the early saints were forced to go through. That said, I think Thomas Ford comes off rather better than he should. Humanizing Ford is something of a fashionable (and I believe overblown) trend in recent historical works on Nauvoo. My own hunch is that this trend stems from the clearer light thrown on Joseph’s theocratic leanings in his final years. Regardless, Turner’s skill at empathetic humanization is a definite strength.

Which brings us to my minor criticisms. Perhaps because of the significant complexity and mystery of Joseph as a person, Turner often shies away from evaluation. As already noted, this is sometimes appropriate, given the lack of empirical evidence. But after walking through several hundred pages of an out-and-out crazytown drama, the reader could use a bit more high altitude surveying of the landscape. For example, Turner certainly captures the volume and complexity of Joseph’s city and people building, but is silent on his success or competence in this arena. Did it result from prodigious talent or accident or something else?

While Turner doesn’t miss the fact that Joseph Smith’s revelations deeply move and inspire his followers—then and now—the book does little to help the reader understand why and how this is so. He’s not a theologian, and here Bushman far outshines Turner (if the reader can make it through RSR); but he also doesn’t pretend to be. Turner certainly does a solid job comparing some of the major theological differences between Joseph’s developing theology and the rest of Christianity, making it clear where things like temple rituals answered deep human questions and yearnings (see 132-133, and 250). Although brief, the epilogue notes how remarkable it is that Joseph’s work has had an immense, intimate, and enduring impact, while writings of such luminaries as Finney, Emmerson, and Thoreau fail to orient the lives of millions devotees all over the globe the way Joseph’s do. This point needs more unpacking.

A more specific and perhaps the most conspicuous example of Turner dodging analysis and evaluation concerns the mystery of the Book of Mormon’s appearance. In a moment of personal narration Turner stated that he didn’t want to get too bogged down here. And of course, on the face of it the story of gold plates and angels and miraculous translation is a tough claim for any gentile to take seriously (to say nothing of members). And Turner certainly spends time with the Book of Mormon, analyzing the text itself to a greater degree than most. But although he admires Hickman’s “Americanist” approach, he’s not a literary analyst and is happy to rely on Mark Twain’s assessment. He expresses far more faith than I have in the literaratti’s neglect of the text. His brief evaluation merely regurgitates the standard list of challenges to the claims of historicity (though thankfully he doesn’t get bogged down here either).

Worse, however, he doesn’t bother to regurgitate or even acknowledge the standard list of challenges to the skeptic’s account (though he at least acknowledges the implausibility of a Spalding-type account). It’s true, as Turner notes, that any believer has to respond to 19th century anachronisms in the text, heavy biblical quotations, the lack of archaeological evidence or semitic DNA amongst America’s indigenous, and in general the utterly fabulous nature of Joseph’s whole account. Turner fails to note, however, that anyone dismissing Joseph’s account has to grapple with the wholly unprecedented speed of the book’s production (in combination with the clear historical evidence that it was in fact produced), the complexity on multiple levels of its internal content (whether or not that content is “literary”), and the various witnesses themselves.

Although Turner spends a whole chapter on the witnesses (almost exclusively focused on the 3 & the 8, largely ignoring various others), the full extent of his analysis consists in another dismissive (though funny!) one-liner by Mark Twain. On the whole, Turner offers one side and then leaves the reader mired in the standard polemics rather than helping us move past them and to the genuine mystery of the Book of Mormon’s appearance and ontology.

Part III: My brief conclusion in the form of two powerful lessons I gained while reading:

With President Nelson’s talks and books like Patrick Mason & David Pulsipher book Proclaim Peace, we’ve had something of a sustained emphasis on peacemaking in the Church in recent years. It’s a theme that my fundamentally conflicted heart has wanted to fully embrace. Joseph Smith’s life brightly illustrates the power of peacemaking and the particular dangers of flirting with conflict—especially in a context as violent and backwater as 19th century America. Turner’s account of Joseph’s surrender to Carthage focuses on the interpersonal, but the surrender itself together with the aftermath of his assassination brightly illustrate the nobility our people have at times achieved through non-violence.

We must be peacemakers. Joseph’s own revelations make this clear, though he at times failed in this undertaking, and not simply because of the culture of honor that RSR richly explores. We’re all familiar with the faith-promoting story (true as far as I know, even if it didn’t find its way into this biography) of Joseph’s inability to translate the gold plates one morning after a fight with Emma. It wasn’t just Emma. Every time he courted conflict or engaged in any kind of violence, Joseph ultimately lost out (even if he “won” the fight; his beating of Walter Bagby on 324 is a memorable and sobering example, with Bagby later among the mob at Carthage).

Among his family, in the leadership and councils of the church, on Zion’s March, in Ohio and Missori, and finally in Illinois, disaster resulted whenever Joseph chose aggression. Alternatively, it was reconciliation that precipitated theological and organizational breakthroughs—with Emma, with the Twelve, with his brother William. When reconciliation wasn’t possible, then simply gathering and rebuilding again, focusing on fulfilling the work resulted in the rapid expansion and prodigious flourishing of the settlements of Zion.

The brilliance of this fact can only be seen if we also see and recognize Joseph’s faults and the way that his actions often precipitated the need for reconciliation in the first place. Positively and negatively, Joseph’s life illustrates the potential of what his revelations call us to be: “And again I say unto you, sue for peace, and not only to the people that have smitten you, but also to all people; and lift up an ensign of peace, and make a proclamation of peace unto the ends of the earth; and make proposals of peace unto those who have smitten you, according to the voice of the Spirit which is in you, and all things shall work together for your good” (D&C 105:38-40).

My final lesson: Many of us are attracted to Joseph’s provocative statement “by proving contraries truth is made manifest” (Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1980), 6:428). Never has the power and potency of this phrase hit me more powerfully than to watch not Joseph but Emma Smith during the frenetic Nauvoo period. Intentional or not, Turner’s text makes Emma the clearest hero in this story. We’re all familiar with Emma as the catalyst for the Word of Wisdom (whose impact during Joseph’s lifetime was apparently minimal, as Turner’s book illustrates). She similarly checked and shaped Joseph’s approach on numerous items which we now consider central to the Restoration. For almost two decades, Emma embraced and testified of Joseph’s genuine prophetic gifts, seership, and connection to heaven, while firmly opposing his excesses and his sometimes significant faults. She also adamantly, and in full knowledge, stood firmly against polygamy, without ever letting go of Joseph himself or succumbing to the growing Nauvoo sentiment that he was a fallen prophet. Her life was that of a faithful, steadfast disciple of Christ, who knew Joseph’s faults, who occasionally railed against those faults, and who embraced the Restoration, despite the deep personal toll it took.

Surely among the myriad lessons from the life of Joseph Smith, Emma’s actions are a vital model and lesson for us in the 21st century—all of us who likewise hope to hold onto both Joseph’s Restoration and his latter-day church.

Comments

3 responses to “Review of Turner’s biography Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet”

I think Publishers Weekly was successful in identifying the books main flaw: “Turner lightly contextualizes Smith’s place in American history, but readers wanting a deeper understanding of his influences and contemporaneous events outside his community will wish for more.”

I didn’t love the book as I felt it was underdeveloped in the first half and I found myself wanting to correct facts or phrases as I read, especially in the 1805-1832 portions. I wanted to highlight interesting insights or sources especially early but found too many distractions. I did think the Nauvoo periods pace was narrated well.

I like the author and am happy someone is publishing new books on a topic of interest, but am not sure it will find as big an audience or have the staying power of other books on Mormonism.

Thank you for you sharing the words on Emma. She’s always been the victim/heroine of the JS story for me. I look forward to reading it for myself in full. (and finding out who Lucena Elliot is!)

Really wonderful review. Thank you!