Category: Science

-

Snow, Citizens, and Stewards

It has recently been announced that Steven E. Snow will replace Marlin K. Jensen as the new Church historian. Elder Jensen has been a wonderful historian for our church, bringing both compassion and honesty to the work.I expect this good work will continue under Elder Snow’s direction. I am curious to see what his areas of…

-

Religious Anti-Intellectualism

A few weeks ago two Evangelical scholars authored “The Evangelical Rejection of Reason,” an op-ed at the New York Times lamenting the fact that the Republican primary race “has become a showcase of evangelical anti-intellectualism.” While the Mormons in the race, Romney and Huntsman, were described as “the two candidates who espouse the greatest support…

-

Mormons Do Care about the Earth

Mormons do care about the earth. We care about preserving, protecting, and maintaining it. We care about the earth because 1) We love God, 2) We care about other people, and 3) We believe in the intrinsic value of the earth.

-

Hurricane open thread

It’s going to be a long day for some East Coast readers, but at least you’ve still got Internet. This thread is to share your first-person accounts and post helpful information. My contribution: Weather Underground, the best online source for hurricane tracking information. As of 11 AM EDT Saturday, their tracking map forecasts a storm…

-

Cafeteria Correlation

Karl Giberson’s Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution (HarperOne, 2008) relates Giberson’s journey from fundamentalist Christian student to still-believing but no longer fundamentalist physicist. Chapter 5 of the book critiques the sources of Young Earth Creationism (YEC), primarily George McCready Price’s The New Geology, published in 1923, and Whitcomb and…

-

Home Waters: Recompense

Of his awakening, Dogen says, “I came to realize clearly that mind is no other than mountains and rivers, the great wide earth, the sun, the moon, the stars.” Tinged with enlightenment, you see what Dogen saw: that life is borrowed and that mind itself is mooched. Every day you’ll need something old, something new,…

-

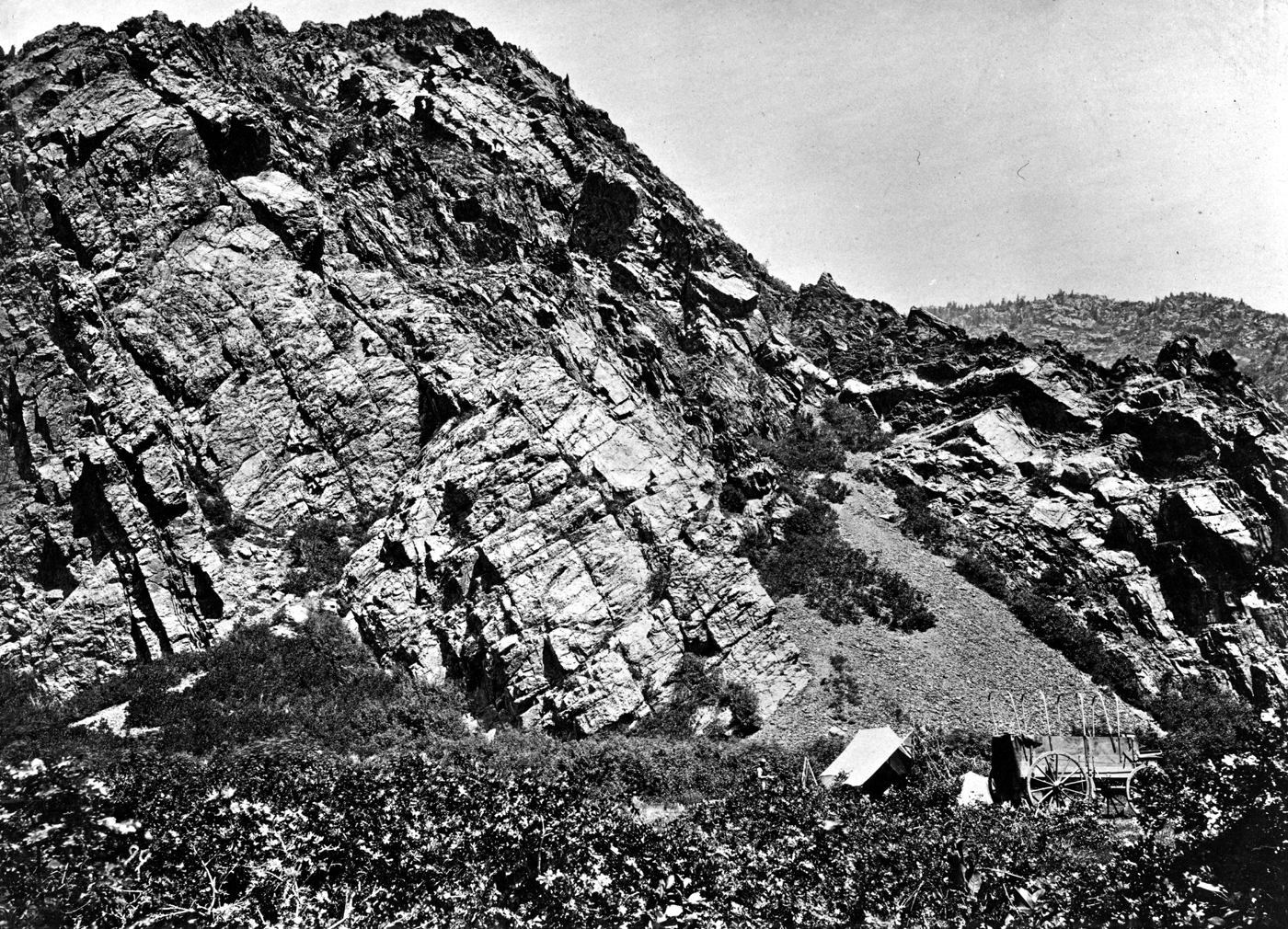

Home Waters: Gene/ecology

Earth is stratified time. Use some wind, water, and pressure. Sift it, layer it, and fold it. Add an inhuman number of years. Stack and buckle these planes of rock into mountains of frozen time. Use a river to cleave that mountain in two. Hide hundreds of millions of purloined years in plain, simultaneous sight…

-

Home Waters: Soul as Watershed

Spurred by Handley’s Home Waters, I’ve been reading Wallace Stegner. Like Handley, Stegner is interested in the tight twine of body, place, and genealogy that makes a life. On my account, Handley and Stegner share the same thesis: if the body is a river, then the soul is a watershed. Like a shirt pulled off…

-

Home Waters: Overview

George Handley’s Home Waters: A Year of Recompenses on the Provo River (University of Utah Press, 2010) practices theology like a doctor practices CPR: not as secondhand theory but as a chest-cracking, lung-inflating, life-saving intervention. Home Waters models what, on my account, good theology ought to do: it is experimental, it is grounded in the…

-

A Writer on Science and Religion

In this final installment of this month’s series of posts on religion and science, I will present a different take on things from the perspective of a celebrated writer. Marilynne Robinson won a Pulitzer Prize in 2005 for her novel Gilead. She also delivered the Terry Lectures at Yale in 2009, resulting in the book…

-

Science and Religion: Enemies or Partners?

For the next installment in this set of posts, let’s consider the relation between science and religion. In a mildly tedious but well-organized book, When Science Meets Religion: Enemies, Strangers, or Partners? (HarperCollins, 2000), Ian Barbour lays out four basic forms that the relation between science and religion can take: Conflict (either science or religion…

-

An LDS View on Science and Religion

Continuing the conversation begun in my earlier post (God and Science), let’s look at the Encyclopedia of Mormonism entry titled “Science and Religion.” It provides a good summary of what might be termed the conservative LDS position on the topic. The article opens on a positive note: “Because of belief in the ultimate compatibility of…

-

God and Science

The conflict between science and religion is generally overstated. But it is certainly true that science is the matrix that most people of our day — believers or not — use as the basis for understanding the natural world we live in. Atheists and agnostics stop there; believers add a supplemental layer of faith to…

-

Writings in the Stone

Some years ago I sat in a Gospel Doctrine class taught by a physician. I mention his profession because I think it matters, as he took the opportunity to deviate from the lesson and condemn in the strongest terms the theory of evolution. He labeled it a satanic concept, one that we must avoid, one…

-

The Downstream Principle of Language

I’m posting this at Times and Seasons as follow-up to a three-part series I wrote here a couple years back (see here, here and here). I’ve cross-posted it over at A Motley Vision’s companion blog Wilderness Interface Zone. September 17th marked the two-year anniversary of the closing of Crossfire Canyon (real name: Recapture Canyon) to…

-

He Is Not in the Desert

“So if anyone tells you, ‘There he is, out in the desert,’ do not go out; … do not believe it” (NIV Matt. 24:26).

-

January 1 of the year 40

Happy Moonlanding Day! When I was a youth, I read a science fiction book in which dates in the future were figured from the day that Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, apparently because the date had such significance in the history of man.

-

Things to be thankful for

If the gravitational constant were just a little bit different than what it is, you would not be here. Nor, for that matter, would anything else. So we’ve got that going for us.

-

Four sources of the Apocalypse

With the past two months, I have read — for various reasons — four different novels laying out apocalyptic events within the United States. Here are the novels, in the order I read (or re-read) them, and with the reasons why I read them: — Lucifer’s Hammer by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle (1977): a…

-

Spooky action at a distance

I am a total NPR dork. I would LOVE to have Carl Kasell’s voice on my answering machine; when I was in middle school, I felt betrayed when I learned that Lake Woebegone wasn’t a real place; and I admit that I joined Ira Flatow’s Science Friday Facebook group (“for those who love Science Friday.…

-

Nature and Cities

I often find walking in nature a spiritual experience, for want of a better term. Growing up, I think that I found my testimony in part by tramping through the Wasatch Mountains and watching thunder storms roll across the Great Salt Lake. Today, I am likely to have real moments of reverence and gratitude to…

-

Mormons, Politics, and Morality

Some of the thoughts of a commenter on my last post, got me thinking about Mormons, politics, and morality. My observation is that the issues that set off moral alarm bells for most Mormons are those that deal with issues relating to what I would consider “freedom to sin†or “prohibitions of obvious sins.â€

-

Changing Conceptions of Zion

The Mormon conception of Zion has changed dramatically over the past century. Today’s members of the church are likely to define “Zion” as wherever the members of the church are: LDS homes, congregations, and stakes. While the conception of Zion in the 19th century may have included these elements, these Saints were determined to literally…

-

Meet Your Inner Fish

I recently read Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion Year History of the Human Body (Pantheon Books, 2008) by Neil Shubin, a paleotologist and professor of anatomy at the University of Chicago. By coincidence, Jared at LDS Science Review had posted the same book in his “Currently Reading” list. Here is our conversation…

-

Why Joseph Went to the Woods

Joseph Smith went to the woods because he wished to know the truth of his existence.

-

A Walk into the Moon

I hope some of you grabbed your moon glasses and stepped outside to have a look at how that full moon lights up the world. Thirty thousand miles closer than usual and thirty percent brighter, tonight this lesser light has a chance to really shine.