Category: Social Sciences and Economics

-

Why the Nones are Rising

One of the most interesting demographic shifts of the last era is the rise of the Nones. These are people who don’t self-identify with any particular religion at all. I’ve written about them several times in the past. My own view is that the rise of the Nones has primarily been a shift among people…

-

Zion as Superorganism

Earlier this month, I visited Utah to give back-to-back presentations at conferences by Mormon Scholars in the Humanities and the Mormon Transhumanist Association. Today, I’m going to recap my presentation from the MTA conference, “Zion as Superorganism.” In subsequent blog posts, I’ll share some thoughts about Mormon transhumanism and the rest of the MTA conference (including some of…

-

Go the Distance

I was struck in yesterday’s morning conference session by the quotation Elder Renlund gave, “The greater the distance between the giver and the receiver, the more the receiver develops a sense of entitlement.” What gave me pause at this, since I agree with the statement, is a simple question: What do we do about the…

-

Utah Transcends Political Tribalism

This might be the last place you would expect to see it: a state where Republicans already prefer the inclusive message of Marco Rubio over the divisive messages of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz,* even before Rubio’s strong finish in South Carolina.** That is, if you didn’t know much about Utah. Utah is the reddest…

-

“That They Might Have Joy”: Conquering Shame Through At-one-Ment

*Film spoilers* Steve McQueen’s 2011 film Shame is one of the most devastating movie experiences I’ve had in recent memory. I’m wading into potentially touchy Mormon territory given its NC-17 rating and subject matter, but I think it’s worth the risk. In short, the film follows Brandon (an incredible Michael Fassbender) as he struggles with his all-consuming sex addiction;…

-

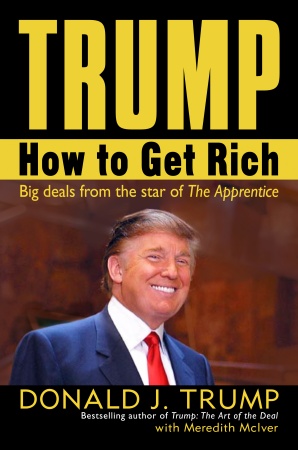

The Approaching Zion Project: How to Get Rich

So here we are, a day early (or, um, six days late, if that’s the way you want to look at it). Since we’re here, let’s take a look at Nibley’s next approach toward Zion:

-

The Approaching Zion Project: How Firm a Foundation! What Makes It So

Interestingly enough, this chapter seems to be less focused on Zion and more focused on the Church more broadly. Still, Zion sneaks in, even discussing the Church. As always, a couple things I found interesting:

-

The Approaching Zion Project: Deny Not the Gifts of God

This chapter (understandably) overlaps significantly with the previous chapter, Gifts. These are, after all, discourses he delivered at various times, to various audiences, with common themes. I’m reading them separately, though, and different things hit me at different readings. So, like always, I won’t discuss everything Nibley focuses on (and I’ll try to not spend…

-

The Approaching Zion Project: Gifts

For the third (and, I hope, final) time, I read this chapter on an airplane, taking notes as I read it. And there are just a couple quick things I want to highlight and discuss, and one sentence that really troubled me.

-

The Approaching Zion Project: Zeal Without Knowledge

For the second time, I read this chapter in an airport and on an airplane returning home. With that as my full preface, let’s jump into this chapter:

-

The Approaching Zion Project: What is Zion? A Distant View

Another confession: I had a really hard time with this chapter. And it’s not just because I read it sitting in an airport waiting for a plane that was delayed for an hour and a half. Rather, it’s because of the way Nibley speaks of the wealthy. Certain of his descriptions feel, to me, so…

-

The Approaching Zion Project: Our Glory or Our Condemnation

Now that I’ve read my first chapter of Approaching Zion, a couple more caveats before we get started. First, I’m not going to bother summarizing what Nibley said. Instead, I’m going to try to engage it, responding to ideas that engaged me, whether I agree or disagree. Second, I’m not going to try to engage…

-

The Approaching Zion Project: Prologue

I have a confession to make: I’ve never read Hugh Nibley’s Approaching Zion. I’m serious. I mean, I bought it years ago, probably before my oldest daughter was born. I’ve lugged it through at least six or seven moves. And it’s sitting on my bookshelf, taking up valuable real estate. But, though I’ve nibbled here…

-

-

Facebook Memes and the Property Tax

There is, I’ve been told, a Facebook meme going around, juxtaposing a decaying house and the San Diego temple to support the argument that churches should not be exempt from taxation. And, like Facebook memes everywhere, this one is dumb. Dumb primarily because it is a tautology that doesn’t say anything. Because of course a…

-

Entirely Privately

When I lived in New York, I could have told you what virtually all of my friends paid in rent. It was a fairly common topic of conversation, and the conversation was one of two types: the can-you-believe-I-pay-$2,000-for-this-dump, or can-you-believe-I-only-pay-$3,500-for-this-apartment.[fn1] I didn’t really think much of it; I didn’t put much stock in financial privacy.…

-

Charitable Profit

About six months ago, I got an email asking (a) if I knew anything about low-profit limited liability companies (“L3Cs”) and private foundations, and (b) if I’d be willing to be a guest lecturer in a class, explaining what they were and how they function. I did know something (though at the time not much)…

-

Taxing Churches: A Response

Oh no—somebody on the Internet is wrong while I’m on vacation! But duty calls. Recently, Ryan Cragun, a sociology professor, along with students Stephanie Yeager and Desmond Vega, argued that the government subsidizes religion by about $71 billion a year. He thinks this is wrong, and that religions should pay their fair share. I have…

-

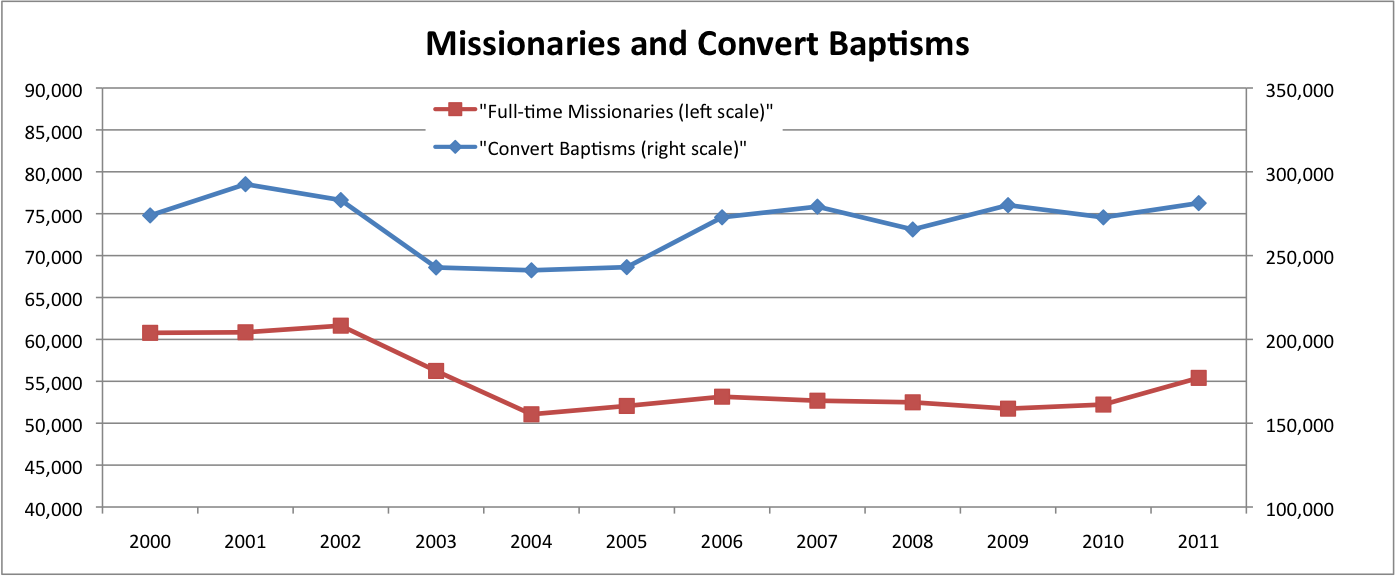

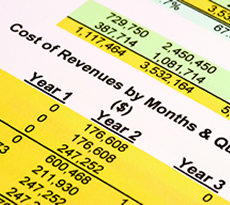

The Implied Statistical Report 2011

Over the past few years I’ve put together an analysis of the cumulative information in the Church’s statistical reports. Three years ago I posted The Implied Statistical Report, 2008, and last year I titled my analysis The Implied Statistical Report, 2010. Over this time I’ve tried to improve my methods and the data available, collecting…

-

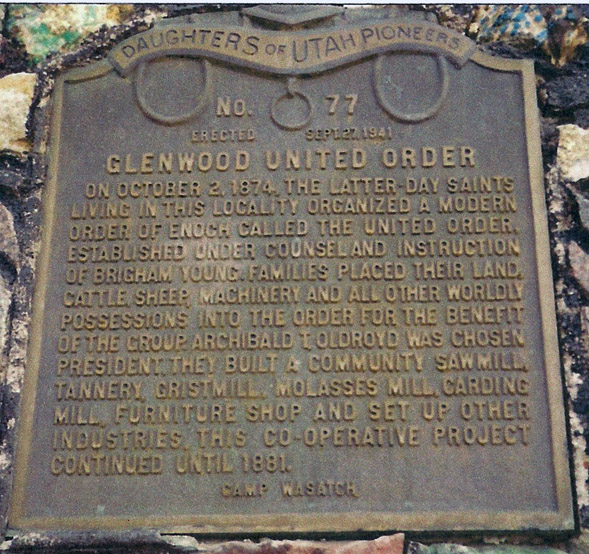

Taxing the United Order

The United Order appears (for now, at least) to be a relic of the 19th century; since them, the mainstream Mormon church hasn’t attempted to institute any large-scale communal economic structure based on Acts 2. And, frankly, I don’t have any reason to think that it will in the 21st century; the Law of Consecration…

-

Sex-Ed and Social Justice*

***WARNING: This post mentions sex. I use the word a lot in this post. If that makes you uncomfortable, this may not be the post for you.*** Over the summer, the Bloomberg administration announced that, for the first time in two decades, public school students in New York would be required to take sex-ed. The…

-

Interest Never Sleeps

Hypothetical:[fn1] Alex and Pat both want a Kindle Fire.[fn2] Alex goes to the local brick-and-mortar[fn3] Amazon store, pays $200 cash, and takes a Kindle Fire home. Pat goes to the bank, gets a loan for $200, goes to the local brick-and-mortar Amazon store, pays the $200, and takes a Kindle Fire home. Who made the…

-

Utah Women in the Labor Market

The Atlantic Cities, currently one of my favorite sites, has, over the last several days, run a series looking into the best states for working women (both generally and in the “creative class”). What leaped out at me: Utah’s a pretty bad place to be a working woman.

-

Mormons and Muslims

I had a university professor who lived in Iran and ran a television program dedicated to classical Persian music prior to the Islamic revolution. He spent a lot of time during the seventies crossing sketchy borders into various ‘Stans. One of his tools for successful border crossing (not to mention survival) was a pamphlet he…

-

The Church and Taxes

The Church cares about taxes.[fn1] It doesn’t really seem to care about the details of tax policy, of course. I’ve never seen the Church weigh in on the appropriate tax rate, tax base, or even the appropriate type(s) of tax (e.g., an income or consumption tax, a retail sales tax or a VAT, or whatever) a…

-

Consumerism vs. Stewardship

The following is a modified excerpt from my presentation at Sunstone this summer. We live, not only in a capitalist, but a consumerist, society. Our society is all about spending, acquiring, cluttering, and replacing, not about maintaining, restoring, renewing, and protecting. It is cheaper to buy new than to repair old. We live in a…

-

Desert and a Just Society

The 2010 poverty level in the U.S., we learned on Tuesday, is the highest it has been since 1993. In 2010, about one in six Americans lived below the poverty line.[fn1] In June, 14.6% of Americans received food stamps.[fn2] To some extent, the high poverty rate is probably related to the high unemployment rate, which…

-

Mormonism and Social Justice

Recently, we’ve seen some distrust of religions that advocate social justice, from sources as diverse as the political punditry and lay Mormons.[fn1] The criticism is unfounded, of course, and strikes me as ahistorical and anti-Catholic. The term “social justice” comes from 1840, when the Jesuit scholar Luigi Taparelli as he worked through the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.…

-

What If President Monson Endorsed Mitt Romney?

In his talk at the close of the April 2008 General Conference, President Monson talked about the blessing we had received, both as members of the Church and, specifically, over the course of the conference. He ended his talk with counsel: parents are to love and cherish their children, youth are to keep the commandments,…