Category: Book of Mormon

-

Seer Stones and Grammar

Book of Mormon translation is one of those interesting subjects that is central to the ongoing Book of Mormon wars. As well, to me, one interesting aspect about the Book of Mormon is how self-aware of its own creation it is. For example, in Mosiah 8 (part of this week’s “Come, Follow Me” discussion), there…

-

Review: Buried Treasures: Reading the Book of Mormon Again for the First Time

Michael Austin’s book, Buried Treasures: Reading the Book of Mormon Again for the First Time is a quick, insightful and though-provoking read about the Book of Mormon. The book began its life as a series of blog posts at By Common Consent, documenting some of Austin’s thoughts as he read the Book of Mormon in-depth…

-

Race and Lineage among early Latter-day Saints

Race is an incredibly sensitive topic, but it is also an incredibly important topic to discuss and understand. A number of important books have been published about the racial narratives that were adopted by early members of the Church in recent years, including Max Perry Mueller’s Race and the Making of the Mormon People (The…

-

Revisiting Sherem

Many of my choices in books this year have been influenced by a decision to try and catch up on literature about the Book of Mormon. I feel a bit overwhelmed, to be honest, since there’s a lot out there and I have been more focused on the New Testament in recent years. I recently…

-

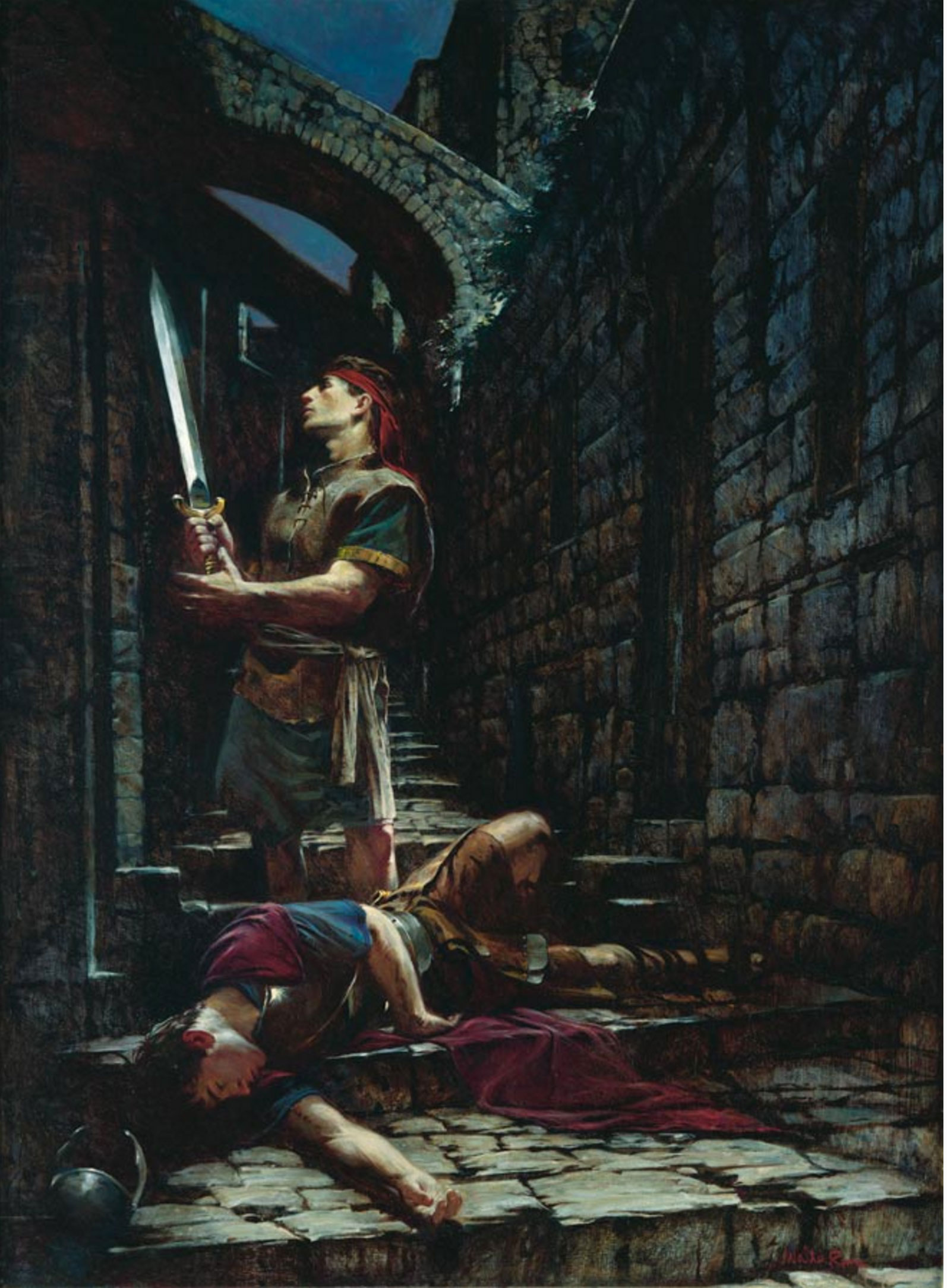

Laban… as a Christ Figure?

This Holy Week I’ve been monitoring my employer’s livestreamed Roman Catholic masses and services, meaning that I (for the first time) attended a Holy Thursday mass and a Good Friday service. So it happened that, during the reading of the Gospel of John in the Good Friday service, I noticed something peculiar. In response to…

-

Resurrection and the Timing of Healing

Bear with me as I go out into the theological weeds to explore an obscure doctrinal debate about the resurrection. As my wife and I studied the “Come, Follow Me” curriculum section on Easter, we discussed Amulek statements about the resurrection in Alma 11. Our question was: What exactly does it mean to “restored to…

-

The Way and the Ancient Gospel

Along with “baby Yoda” memes, Disney’s Mandalorian made two phrases trendy: “This is the way,” and “I have spoken.” Being a Star Wars fan, the phrases quickly made their way into the lexicon of my household. So, it was humorous to me to find an entire lesson in “Come, Follow Me” this year entitled “This…

-

The Olive Tree Restoration

There have been some common underlying themes to several Times and Seasons posts these past few months. The three themes or questions that I have in mind at the moment are: “What is the nature of the Great Apostasy?”, “What is the nature of the Restoration?”, and “What is the relationship of the Church of…

-

Embracing Jacob’s Sermon

One of the more awkward moments of my time in graduate school came when I was reading a book about Mormon polygamy while taking a break in the lab. A visiting scientist from Pakistan who was doing research in the same lab saw me reading the book and asked me: “That looks like an interesting…

-

Sacrament Prayers and the Doctrine of Christ

I am always interested in seeing how ideas grow, develop, and take shape of the years. I suppose that is part of why I find the study of theology so interesting. As I was studying the “Come, Follow Me” curriculum this last week, it struck me how the sacrament prayers seem to have developed and…

-

The Crux of Historicity

For all their differences, the essential and irreducible historical dilemma of the Old Testament, New Testament, and Book of Mormon is very much the same.

-

What Has Isaiah To Do With Nephi?

In the neighborhood where I grew up, there was a yard that had landscaping that baffled me. It was a grassy plain with a few small trees, and then about a half-dozen boulders scattered among the grass. The boulders were what baffled me—they didn’t seem to fit in with the landscaping around them and they…

-

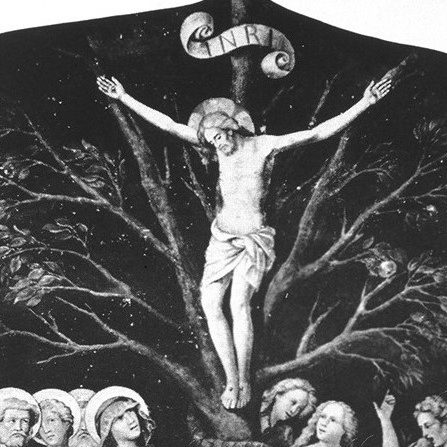

Reflections on the Tree of Life, Part 3: Christ and the Tree

The tree of life and its fruit mean many things to many different people. Immortality, eternal life, the presence of God, and Jesus the Christ are all important meanings of the tree in our tradition, but many more could be stated. Among Christians, one prominent meaning of the tree of life is as a symbol…

-

Reconsidering the Lamanites

One of the major points of discussion in recent weeks is over an error in the printed “Come, Follow Me” manual. A Joseph Fielding Smith quote with racist content was included in the discussion of 2 Nephi 5 and it was only noted that it does not accurately reflect Church doctrine after the manuals were…

-

The Church of the Devil and the Church of the Lamb of God

One of the more controversial aspects of Nephi’s vision of the tree of life is the great and abominable church or church of the devil. In his record, Nephi states that “there are save two churches only; the one is the church of the Lamb of God, and the other is the church of the…

-

What are the best books to accompany your study of the Book of Mormon?

Next year, we’ll be studying The Book of Mormon in the Come, Follow Me program for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. During this year’s study of the New Testament, I’ve benefited from reading complementary material, such as — as I was reading Romans — Adam Miller’s excellent Grace Is Not God’s Backup…

-

Putting the Book of Mormon Front and Center

Elder B.H. Roberts of the Seventy once wrote that: So long as the truth respecting it is unbelieved {the Book of Mormon} will remain to the world an enigma, a veritable literary sphinx, challenging the inquiry and speculation of the learned. But to those who in simple faith will accept it for what it is,…

-

On Not Understanding the Atonement

There are some pretty major aspects of our Latter-day Saint faith–and of Christianity in general–that I don’t really understand. Specifically: the necessity and efficacy of the Atonement. Repentance and forgiveness make sense to me. The Atonement is a mystery, and none of the explanations or theories resonate with me on a deep, personal level. I…

-

A Reaction to the Church’s Recent Essay on Book of Mormon Geography

Brant Gardner has kindly agreed to offer some comments on the recent Church essay on Book of Mormon geography. He’s a research assistant with Book of Mormon Central and arguably one of the top experts in the question of Book of Mormon geography. I’ve enjoyed discussing the Book of Mormon with Brant going way back…

-

Uto-Aztecan and Semitic: Too much of a good thing

Brian Stubbs’s argument for extensive ancient contact between Semitic and Proto-Uto-Aztecan has received some attention recently in Mormon apologetics, but I don’t think Stubbs’s proposal is going to pan out. First, though, a few important messages.

-

Some Thoughts on WordPrint

Just a quick post on the current kerfuffle over wordprint studies. Wordprint studies are a type of stylometry that look at certain connective words that aren’t main words in a sentence. The claim is that they can determine the authorship of a text. Now I’ve always been skeptical of this, even back in its heyday…

-

Helaman 12:15 and Astronomy

Helaman 12:15 reads, “according to his word the earth goeth back, and it appeareth unto man that the sun standeth still; yea, and behold, this is so; for surely it is the earth that moveth and not the sun.” If you’re like me you’ve always just read that as Mormon (or possibly Nephi) just having…

-

Coming Soon to a Screen Near You: The Book of Mormon

Not the big screen, just lots of small screens. From the LDS Newsroom: Filming Begins on New Book of Mormon Videos. It will not be a beginning-to-end depiction; the project will select certain episodes and events, producing “up to 180 video segments three to five minutes in length, as well as up to 60 more…

-

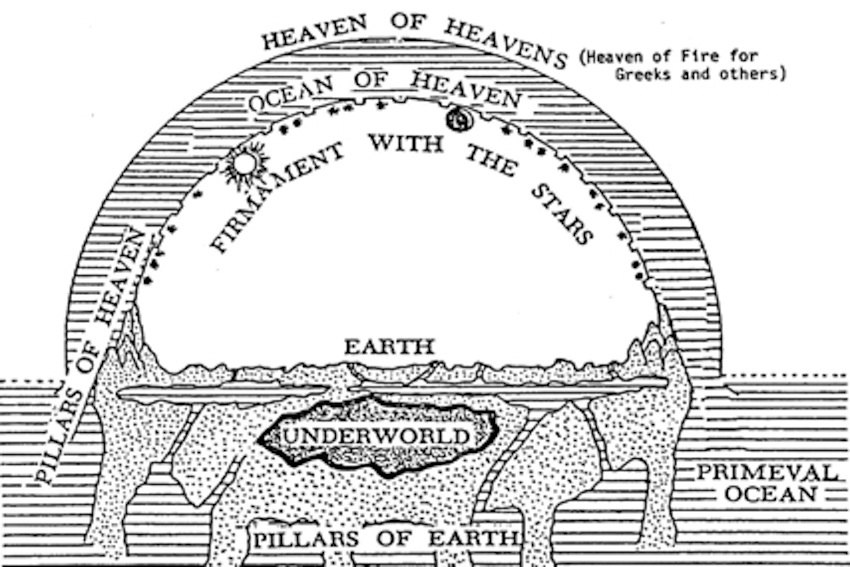

The Book of the Weeping God

One of the most striking features of the Bible is its division into Old and New Testaments, which present not only substantially different sets of religious beliefs and practices, but very different portrayals of God. The God of the Old Testament is a judgmental, jealous, and vengeful God, who destroys sinners without remorse, whether of…

-

Can Mercy Rob Justice?

We’re all familiar with Alma 42 and the notion that mercy can’t rob justice. I was reading this today at church and was struck by a context that often doesn’t get mentioned. In the ancient world relationships often determined actions. This meant special treatment for friends and especially relations. In Greek philosophy and plays you…

-

Korihor the Witch

Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live. (Ex. 22:18) I recently read Peter Charles Hoffer’s The Salem Witchcraft Trials: A Legal History (Univ. Press of Kansas, 1997). How could a bunch of dedicated Christians become convinced that their neighbors, some of whom were acknowledged to be fine citizens and exemplary Christians, were actually in…

-

Hell Part 1: Close Readings of the Book of Mormon

I love doing close readings of scripture. The normal way to do this is reading linearly through the entire book of scripture. An other great way is to study by topic. Each helps you see things you might miss using only the other method. While I’m glad our gospel doctrine has encouraged reading all scripture, part…

-

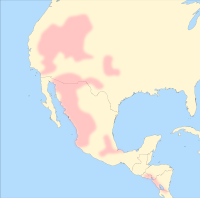

Day of the Lamanite, Deferred

Lamanite: An increasingly dated term that now rubs many people the wrong way when heard in public Mormon discourse. But the category lingers on despite LDS attempts to move toward a post-racial approach to priesthood and salvation. Lamanites, Nephites, children of Lehi, Indians, Native Americans, Amerindians — whichever term you choose, it’s clear the doctrinal…

-

The Book of Mormon as Literature

One can read the Book of Mormon as canonized scripture, to guide the Church and its members in doctrine and practice, or as a sign of Joseph Smith’s calling to bring forth new scripture and establish a restored church. Then there is the possibility of reading the Book of Mormon as literature, to enlighten, uplift,…

-

Partaking of the Fruit of the Tree

One of my favorite parts of Christmas is sitting in the darkened living room, gazing at the lighted tree. There is something magical and transfixing about the warm, gentle light, the fragrance of pine, and the palpable presence of nature that fills my home with its incongruous beauty. I have many memories of reading Scripture…