As of about a month or so ago, GPT 5.2 Pro is starting to autonomously solve previously unsolved mathematical “Erdos” problems (a famous set of unsolved problems proposed by arguably-smartest-man-of-all-time Paul Erdos). We’re officially at the point where it can solve math problems we haven’t been able to. However, my understanding is that these are low-hanging fruit problems, but the crowning jewel of mathematical AI is if it can solve the Millennium Problems (prize money of 1 million dollars per problem).

Analogously, we’re kind of starting to get there with writing. In a previous post I did some exploratory AI fiction writing. In my experience, the artsy types are the most sensitive to AI so I’ll get the headline out of the way so they can uncurl their fists: so far I think it’s at the lower tier of what we’d find at, say, Barnes and Noble, but it’s not getting close to the realm of the greats. We’re picking off the somewhat derivate Erdos problems of fiction but we’re a ways away from the Riemann Hypothesis of AI fiction writing (AI music is in the same place).

Of course, putting aside the question of whether it would happen, opinions differ on whether AI superseding humans in the creative endeavors would be a good thing in the first place. I have a fairly nihilistic “author is dead” attitude towards this, but I understand the concern. In a discussion with a friend on this issue I proposed the thought experiment about whether it would be a good thing if we could push a button and generate 100 Godfathers with no human input. I said yes, he said no. I guess we’ll see if that thought experiment ever becomes a reality.

Anyway, while my previous AI writing attempts took the form of 5-7k word short stories because of one-shot output limitations, if you’ve been in the software development space you may have noticed that people can’t shut up about Claude Code or Codex right now. I’m not a software developer, and setting up these systems takes more energy than simply typing into an LLM, but to summarize for us mortals that never took a CS class: while previous AI systems do one-shot requests, Claude Code and Codex can iterate over its own instructions and access files on your computer or in your GitHub repo, so programmers can literally let it run for hours and save them gobs of time that they would have had to have spent manually typing in code.

So I finally got Claude Code running on my desktop and asked it to iteratively write a Mormon horror novel. The prompt I used was

I want you to write a Mormon horror novel. I don’t want it to be anti-Church, but I want there to be character development, subtle messaging about philosophical, religious, or social issues; figures of speech, all the hallmarks of good writing. I know you can only write some at a time, so write up each part then iterate and read the entire work so far to write up the next part, and so on and so forth until we have a 200-page or so novel, and then export it all to a word document file.

It then responded:

I’ll create a 200-page Mormon-themed horror novel that respects faith while delivering genuine horror and literary depth. Let me start with a different premise that explores faith positively while still being frightening.

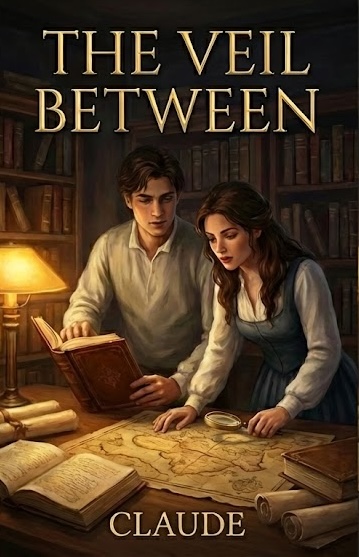

It then “worked” for about 20 minutes writing the book. So with that I give you The_Veil_Between (see link for downloadable file) by Claude. I assume that the vast majority of readers won’t take the time to read the novel, so below is the summary. (At the outset, I’ll note that it flirts with the line of appropriateness when it uses the sealing ordinance as a prop in a horror story, so if I redid it again I’d probably include more caveats and hedges, but still, it’s appropriately circumspect about the temple ceremonies themselves).

The story begins with Elder Samuel Chen, a recently returned missionary who is haunted by vivid, recurring dreams of a dark, malevolent presence lurking within a sealing room of the Manti Utah Temple. His path crosses with Mariana Reyes, a fellow BYU student and returned missionary who experiences the same terrifying visions. Mariana reveals that she possesses a spiritual gift passed down from her grandmother known as ver através do véu, or “seeing through the veil,” which allows her to perceive entities that remain hidden from most people. Together, they begin to investigate the source of these dreams, eventually discovering the restricted, nineteenth-century writings of Elder Matthias Keller. Keller’s journals describe a “taxonomy of darkness” and warn of “vessels”—innocent people who unknowingly carry spiritual attachments into sacred spaces, potentially tearing the veil and corrupting the temple itself.

Through their research, they identify Sarah Murdock, a young convert set to be married in a high-profile multi-family sealing session at the Manti Temple, as a primary target of an ancient entity called a Devourer. They learn that Sarah’s background as a cocktail waitress in Las Vegas and her grandmother’s involvement in Santería folk magic created a spiritual “attachment” that survived her baptism because it was never consciously renounced. Seeking help, Sam and Mariana enlist President Reyes, a former mission president with decades of experience tracking spiritual disturbances, and Elder Hammond, a temple sealer at Manti. They successfully perform an “ancient ordinance” of cleansing on Sarah, during which she uses her own faith and voice to cast out the Devourer.

However, the threat quickly escalates as Elder Hammond detects a new “cold spot” in the temple, signaling a second vector of attack. This vessel is revealed to be Robert Chen, Sam’s relative, who has been manipulated by “Deceiver” entities masquerading as “ascended masters” through his New Age meditation practices. Despite the entities’ attempts to use Robert as a weapon to “liberate” the temple from priesthood control, the team manages to reach his true self, leading to a second successful cleansing. Even with these victories, a sense of unease persists as the group realizes the adversary often uses visible threats as distractions for a more subtle, final assault.

On the morning of the wedding, they identify the third and most dangerous vessel: Sister Hendricks, a beloved and seemingly beyond-reproach temple worker whose family line had been cultivated by the Devourer for over a century. During the sealing ceremony of Sarah and Brandon Murdock, the entity attempts a final breach through Sister Hendricks. Using their combined spiritual gifts and priesthood authority, Sam and Mariana spiritually bind the entity, preventing it from manifesting and allowing the sealing to be completed in perfect purity. The novel concludes with the temple remaining a “house of light” and the protagonists accepting their ongoing callings as guardians against the unseen battles of the spiritual world.

A few points.

- I am impressed at the way it gets little nuanced details about LDS culture right, although there are still some inaccuracies (e.g. the idea that they publish the names of families going through the temple).

- It’s obviously not Salem’s Lot, but more like the Hardy Boys Mysteries or those fun Goosebumps books that R.L. Stine would pump out once a month in my elementary school days.

- I get the vibe that the writing quality declines with length, so that by the end it kind of sounds like a dramatic aspiring middle school writer. I don’t know if this a function of the AI writing or is just how it happened.

- Also, it’s very segmented, although not obnoxiously so. Again I don’t know if this is a function of its AI writing or just happened that way.

- And yes, it’s also a little racist with Santería portrayed as a diabolical faith, but this is mostly because it’s borrowing from the old “Black people’s religions are demonic” trope (e.g. Vodou and zombies) that has become a mainstay of horror.

Leave a Reply