Since I was young an impromptu thought experiment has intermittently popped up in the back of my head that’s made me think deeply about the nature of (my) modern faith.

Assume that the Church was not restored in 1830, we don’t know anything about the Book of Mormon, and in 2025 somebody knocks on your door and says that God is speaking to man again and that the person’s brother has uncovered gold plates yadda yadda.

A priori the vast majority of us would not give the person the time of day and would think his brother a little loony if not the Samuel Smith character himself. So how should we treat this any differently now than in 1830? I’ve been mulling over this since grade school, and I’ve gradually come to various conclusions.

To start with the more explicitly pro-faith one; if God did restore something like that it would be in an era when people could 1) freely choose a radically different, new faith, and 2) were open to this kind of supernatural intervention, so it makes sense for God to restore a Church in 1830 in America in a way that it wouldn’t in 2025 or in, say, medieval Japan. (Also, the Bayesian prior that you are just going to happen to be one of the first converts to God’s true and living Church seems quite low, but of course somebody has to be the first, so it’s good that the early Church converts were probably less snooty and more faithful than I would have been.)

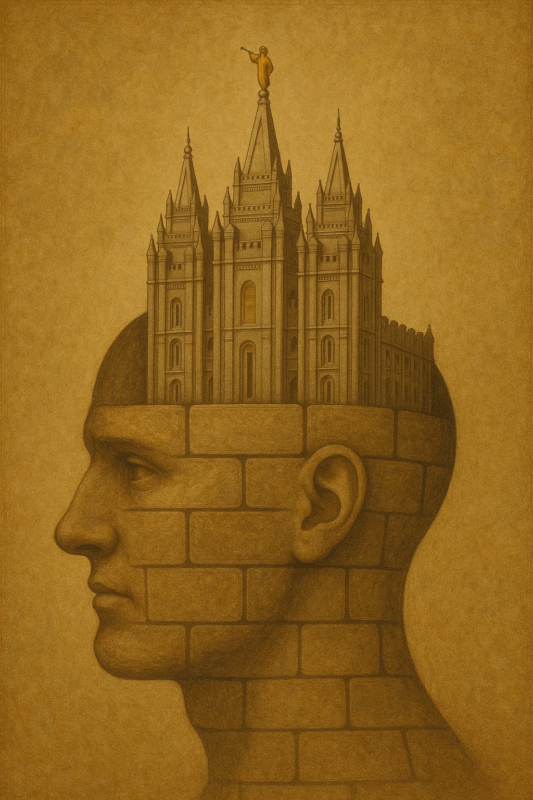

Another realization is how much of our beliefs as humans are based in what sociology has termed plausibility structures (although I intuited the concept before I learned there was an official term for it). Basically, when other people around you believe something it normalizes it because our gut reaction is that there has to be something to it if so many people hold to it. We can intellectually disagree with the premise as a matter of logic, but it’s a natural reflex. A lot more people are going to find Islam plausible in a country that has been Muslim majority for centuries than would in our hypothetical of a Saudi Arabian Mohammad riding out of the desert in 2025. This may be why there is some evidence that Utah Latter-day Saints stay in the Church more (by the way, the author of that piece, Alex at Mormon Metrics has a lot of good stuff on his Substack), although the power of Utah in keeping one in the Church should not be exaggerated, since I believe that the Utah “sacred canopy” has been punctured by the Internet and popular culture. Still, it matters that we have institutions that socialize us and make things plausible. I mean, in large part that’s kind of what a testimony meeting is. By hearing other people affirm a belief it gives us some more room for that Alma 32 seed of faith (if we want it to, and that’s key). But I’d obviously argue that the difference is that God would accompany our testimonies with an added spirit beyond what you’d get in a pure peer pressure exercise, and that the former is exponentially more important for long-term Church retention than the latter.

And less you think this just problematizes religious beliefs, atheism was non-plausible across many generations and places. Yes, occasionally you’d get a quiet atheist in 5th century Constantinople, but that was probably about as common as, say, a Catholic who believes in reincarnation or something, and was more of an idiosyncratic personal belief than some systematic framework developed and reinforced by a community and family across time and space. There’s no reason to believe that non-belief in a God is a more natural, independent belief than believing there is one. So while Dawkins thinks he’s scoring some profound point by often pointing out to his audience that if they were born in Ancient Greece they would just as likely be devotees of Zeus, the same can be said for his (non) beliefs and even his moral beliefs such as “slavery is bad.”

For some, intellectual believers have a prominent role in maintaining plausibility structures. In a world where religion often comes under intellectual as much as emotional or social attack, the beliefs of those who are seen as experts or highly intelligent are particularly important in maintaining plausibility structures. Sometimes this is domain specific (e.g. Egyptologists and the Book of Abraham). While they worked in different fields, I think Richard Bushman and Hugh Nibley both fit in this category. Nibley in a sense gave intellectual types permission to believe in the historicity of the ancient Latter-day Saint scriptures, and in a similar process Richard Bushman with the 19th century history when the Internet started shouting all the spicy history from the rooftops. And the critics know this, which is why there was that weird hullabaloo back when some people tried to depict Bushman as being a metaphorical believer before Bushman had to personally quash that attempt at controlling his narrative.

Speaking more generally, this is why people are obsessed with whether Einstein believed in God. (Although if we’re going to take the “we should believe what smartest person believes” line, then we should all be devotees of Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess to whom the probably-smartest-person-ever Indian mathematician Ramanujan credited his mathematical prowess).

However, in the end I think belief in something as fundamental as God is visceral more than anything, and comes prior to intellectual argument. To quote probably the most intellectually accomplished ex-Mormon of all time, Nobel prize winner Kip Thorne: “There are large numbers of my finest colleagues who are quite devout and believe in God, ranging from an abstract humanist God to a very concrete Catholic or Mormon God. There is no fundamental incompatibility between science and religion. I happen to not believe in God.”

In terms of our own particular truth claims, obviously plausibility structures are, technically, illogical, and are a cognitive bias we’re born with. In principle the “crazy” person on your doorstep in 2025 is just as logical as the Church today. Something shouldn’t be more plausible just because some people believe in it. And plenty of people have believed very illogical things. As I’ve noted before, this can be seen in the interesting history of very smart people with very cooky ideas. All of this makes me respect pioneers that fomented the initial growth environments even more, whether in the 19th century or 21st century, and also explains why they are so rare.

However, as economists will tell you we are not perfect little balls of independent thought that exist in a perfectly objective vacuum operating off of perfect information. We are social creatures that interact and feed off of our environment, and God will use that as a vessel to place the seed of faith in good ground. However, plausibility structure maintenance are for just that, plausibility, we’re not such a hermetically sealed sacred canopy anymore that non-belief is implausible, but there’s just enough good earth, whether being raised in Utah or brought to a small branch in Greece by missionaries, for us to seriously consider whether it might, in fact, be true.

Comments

5 responses to “Plausibility Structures, Intellectuals, and the Church’s Truth Claims”

Hopefully you would have a strong impression from some outside force you couldn’t account for prompting you to listen to the stranger at your doorstep.

I think wealth is a key factor in the difference between modern society and the 1830s vis-a-vis plausibility. Our relative ease gives us more psychological freedom to explore natural explanations for our existence. Whereas the vast majority of folks — and I mean those who have lived as paupers or peasants or servants or slaves — are psychologically constrained by their circumstances to hope for something better–thus causing them to be more open to supernatural explanations than they might otherwise be.

jader3rd: Hopefully, but if you’re not open to it it’s hard to get that feeling.

Jack: Definitely agree.

I do think the nature of the larger culture was conducive to Mormon success in 1830 New York (and thereabouts). Likely providential.

“ There’s no reason to believe that non-belief in a God is a more natural, independent belief than believing there is one.”

This is empirically (although possibly unethically) testable. We could raise children in non-social environments without language until say, age 30, and then attempt to teach them language and see how hard it is to teach them to use the word “God” rather than a word like blue or hunger or food. If it is more difficult to teach them to use God correctly, then I think that it is evidence it is non-belief is more natural and vice versa.

I start with this example, because I am struck by the irony of using the term “visceral” for what is often referred to as “spiritual”.

My opinion is that your thoughts would benefit from more thinking about “cognitive bias” and “visceral bias” as they relate to socialization.

It seemed to me you were exactly clear about what is an inborn bias and what is socialization bias.