This is PART 2 of 6 of an exclusive series for Times & Seasons on “The Tribes that Greeted the Lehites” by Mike Winder. Read Part 1 HERE.

I envision Lehi and his family encountering some curious native villagers near their initial landing beach in the Promised Land. I can imagine that the first Native Americans to see these strangers from the Middle East sailing to their shores in a vessel larger than any canoe may have viewed them as gods. From Christopher Columbus in the West Indies to Hernando Cortés riding into Montezuma’s Mexico, it was natural for the locals to view these otherworldly newcomers as gods. The righteous Nephites would have dissuaded any worship or being treated like gods. Like Ammon later before King Lamoni, they would have denied that they were “the Great Spirit” (Alma 18:18-19). However, it would have been natural for this party of prophets and priests to evangelize to their new friends about the Lord who guided them there.

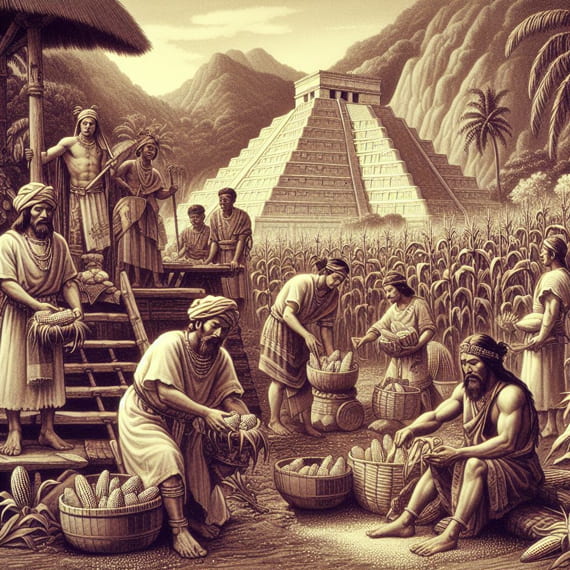

As the Lehites and the Americans became familiar with each other, they would have found great value in sharing ideas, skills, and food. There would have been plenty of new foods for the Jerusalem refugees to enjoy, and Nephi was relieved that the seeds “which we had brought from the land of Jerusalem” did well in the New World soil and “did grow exceedingly” (1 Nephi 18:24). Their new neighbors would have been intrigued by these new crops from the Old World. Think of it as a mini-Columbian exchange. Brant A. Gardner described it this way:

It is probable that the first contact would have been on a level at which the groups did not join permanently, but perhaps a friendly hamlet extended hospitality to the newly arrived people with strange customs. After some time together, residents of the hamlet would have found that the newcomers had enviable skills. The Lehites had come from a much more complex society. The newcomers also worked with metal, an expertise that would be desirable.

On the other hand, the Lehites would have welcomed a friendly hamlet and would have found tremendous benefit in associating with natives of the land. The new land offered new challenges and, for a people who were required to make many of their own personal goods, knowing where to find game, where and how one might cultivate, and where to find appropriate raw materials for such things as pottery and clothing would be invaluable information that would save the Lehites a tremendous amount of time and effort.

Nephi was thrilled to find “beasts in the forests of every kind” in “the land of promise.” But the “cow and ox” of the New World (perhaps bison or shrub-ox), the “ass and the horse” of America (maybe llamas, alpacas, tapirs, or peccaries), and “the goat and the wild goat” of the land (perhaps mountain sheep, yuc goats, or pronghorns) would have taken some getting used to. But when Nephi encountered these “all manner of wild animals,” he was quickly taught by someone that they “were for the use of men” (1 Nephi 18:25). It’s easy to imagine Native Americans teaching the Israelite newcomers how to best use and domesticate the new variety of beasts.

Professor John L. Sorenson pointed out that domesticating both New World animals and the essential crop corn as obvious examples of something the Native Americans would have taught the Lehites. Corn is mentioned in a few places in Mosiah. Sorenson wrote:

Now, “corn” is clearly maize, the native American plant that was the mainstay of the diet of many native American peoples for thousands of years. There is no possibility that Lehi’s party brought this key American crop with them or that they discovered it wild upon their arrival. Maize is so totally domesticated a plant that it will not reproduce without human care. In other words, the Zeniffites or any other of Lehi’s descendants could only be growing com/maize because people already familiar with the complex of techniques for its successful cultivation had passed on the knowledge, and the seed, to the newcomers.

Notice too that these passages in Mosiah indicate that corn had become the grain of preference among the Lamanites, and perhaps among the Zeniffites. That is, they had apparently integrated it into their system of taste preferences and nutrition as a primary food, for which cooks and diners in turn would have had familiar recipes, utensils, and so on. This situation reminds us of how crucial the natives of Massachusetts were in helping the Puritan settlers in the 1600s survive in the unfamiliar environment they found upon landing. The traditional American Thanksgiving cuisine of turkey, pumpkin, and corn dishes–all native to the New World–is an unconscious tribute to the gift of survival conferred by the Amerindians by sharing those local foods with the confused and hungry Europeans. Did an equivalent cultural exchange and unacknowledged thanksgiving process take place for Lehi’s descendants in the Book of Mormon land of first inheritance or land of Nephi?

The God-fearing Lehites were surely grateful for any assistance in getting settled in the new Promised Land. Nephi would have been like his descendant Amulek, who encouraged, “whatsoever place ye may be in, in spirit and in truth; and that ye live in thanksgiving daily, for the many mercies and blessings which he (God) doth bestow upon you” (Alma 34:38).

Mike Winder is the author of 14 books, including his newest, Hidden in Hollywood: The Gospel Found in 1001 Movie Quotes. Illustration by Image Creator from Microsoft Designer with prompts from the author.

Comments

One response to “Lehi’s Thanksgiving”

A “Lehite Thanksgiving” seems quite plausible.

I’m assuming that after Nephi and his followers left the land of their first inheritance Laman and his followers were able to maintain the loyalty of a majority of the local indigenous folk with whom they mingled. My guess is that some of them would have been loyal to Nephi–but if the majority stayed with Laman then that may account for the faster growth rate of the Lamanites.