Category: Scriptures

-

The Metaphysics of Translation

Understanding the nature of Joseph Smith’s translation efforts is an important part of understanding his ministry and the religions that have emerged from the early Latter Day Saint movement. Whether the Book of Mormon, the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, the Book of Abraham, or (as some might argue) the temple endowment ceremony, his…

-

A Small and Simple Quote

As I’ve been studying the “Come, Follow Me” material lately and talking about it with family, I’ve had a quote from Michael Crichton’s book Jurassic Park come to mind a few times. There are a few statements in this section of Alma that have brought it to mind. The first is found in Amulek’s words…

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. Vb4. The utility of philology: Jacob and Sherem

Imagining the Book of Mormon as a complex work reflecting numerous steps of compilation and abridgment helps explain some curious features of the encounter with Sherem in Jacob 7.

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. Vb2-3. The utility of philology: Nephite origins

Thinking of the Book of Mormon as the result of a series of textual accretions and combinations might help make sense of how curiously overdetermined the account of Nephite origins is.

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. V.The permissibility and utility of philology for studying the Book of Mormon

Is philological deliberation useful for studying the Book of Mormon? Is it even permitted?

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. IV. The Puzzle of 3 Nephi

Why is 3 Nephi, which records the central event in the history of Nephite salvation and destruction, located between Helaman and 4 Nephi?

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. IIIc. The source structure of the Book of Mormon

If you trace the history of a text from earlier manuscripts to later ones, it’s not unusual for the text to be extended in various ways.

-

A Lake of Fire and the Problem of Evil

I remember talking to an atheist on the riverfront walk in Dubuque, Iowa one day while serving my mission. He told my companion and me that he couldn’t believe in God after some of the things he had seen, and went on to describe (in a fair amount of gruesome detail) visiting a Catholic church…

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. IIIb note 1. A note on the uniformity of the Golden Plates

Mark Ashurst-McGee asks about the uniformity of the Golden Plates in eyewitness accounts, even though they contain both Mormon’s abridgement and Nephi’s small plates, and this is in fact genuinely weird.

-

Notes on Book of Mormon Philology. IIIa. Nephite literacy

Unless someone gets lucky with a spade or a metal detector, the full extent of Mormon’s sources will remain unknown. To keep even tentative answers on the side of plausibility rather than fantasy, how we think about Mormon’s sources should be informed by any information we have about Nephite literacy and textual culture.

-

Notes on Book of Mormon philology. II. What did Mormon know?

The logical place for a philological approach to the Book of Mormon to begin is with Mormon, its eponymous editor, and his sources. How much did Mormon know about the Nephites, and what kind of records did he have to work with?

-

Notes on Book of Mormon philology. The philological instinct

When I look at recent studies of the Book of Mormon, the biggest deficit I see is the lack of instinct for philology.

-

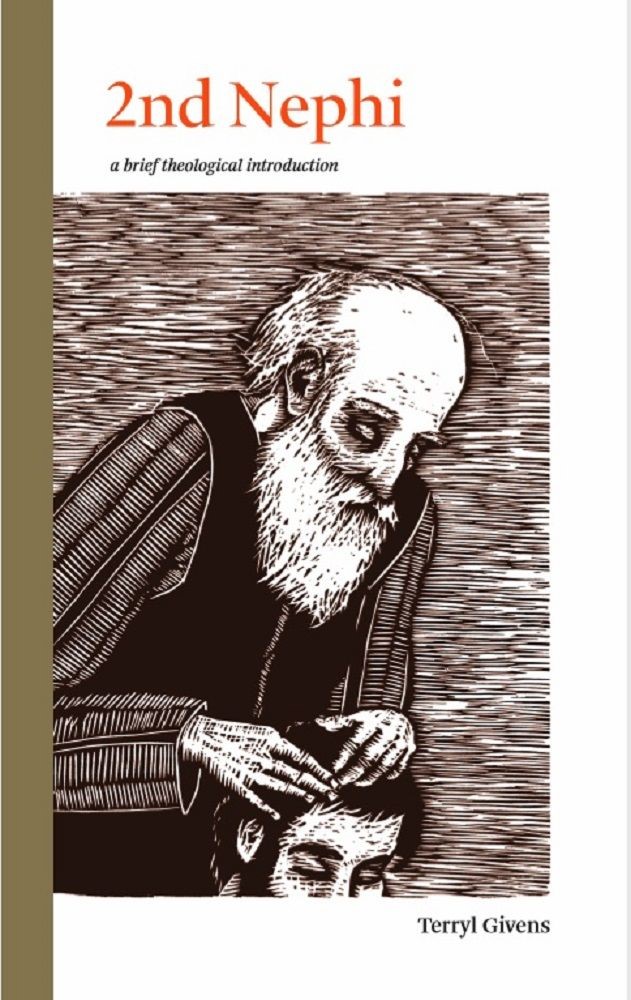

Review: 2nd Nephi: A Brief Theological Introduction

I think one of the most repeated refrains I see in comment threads in the bloggernacle is that our Church meetings generally lack the vibrancy and ability to deeply engage with the scriptures and ideas in ways that can stimulate interest and growth. As Terryl L. Givens put it in a recent interview, “one of…

-

Saving Alvin

How we approach the scriptures affects what we see in them. In other words, our assumptions, our traditions, our cultural baggage that we carry with us as we enter the world of scriptural texts are lenses that give meaning and shape to what we find inside those scriptures. Two approaches that I would like to…

-

Reflections on Meetings in the Church of Christ

One of my favorite quotes of all time about Mormonism focuses on the concept of Zion. “Zion-building is not preparation for heaven. It is heaven, in embryo. The process of sanctifying disciples of Christ, constituting them into a community of love and harmony, does not qualify individuals for heaven; sanctification and celestial relationality are the…

-

Monotheism and Mormonism

One of the most central and difficult issues of Christian theology is how to fit together a commitment to monotheism with a belief that Jesus is a divine being. While we, as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have resolved some aspects of this in our own ways, we still have…

-

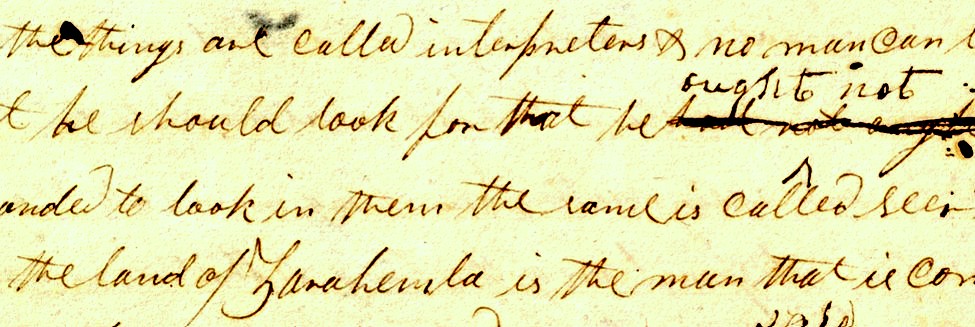

Seer Stones and Grammar

Book of Mormon translation is one of those interesting subjects that is central to the ongoing Book of Mormon wars. As well, to me, one interesting aspect about the Book of Mormon is how self-aware of its own creation it is. For example, in Mosiah 8 (part of this week’s “Come, Follow Me” discussion), there…

-

Review: Buried Treasures: Reading the Book of Mormon Again for the First Time

Michael Austin’s book, Buried Treasures: Reading the Book of Mormon Again for the First Time is a quick, insightful and though-provoking read about the Book of Mormon. The book began its life as a series of blog posts at By Common Consent, documenting some of Austin’s thoughts as he read the Book of Mormon in-depth…

-

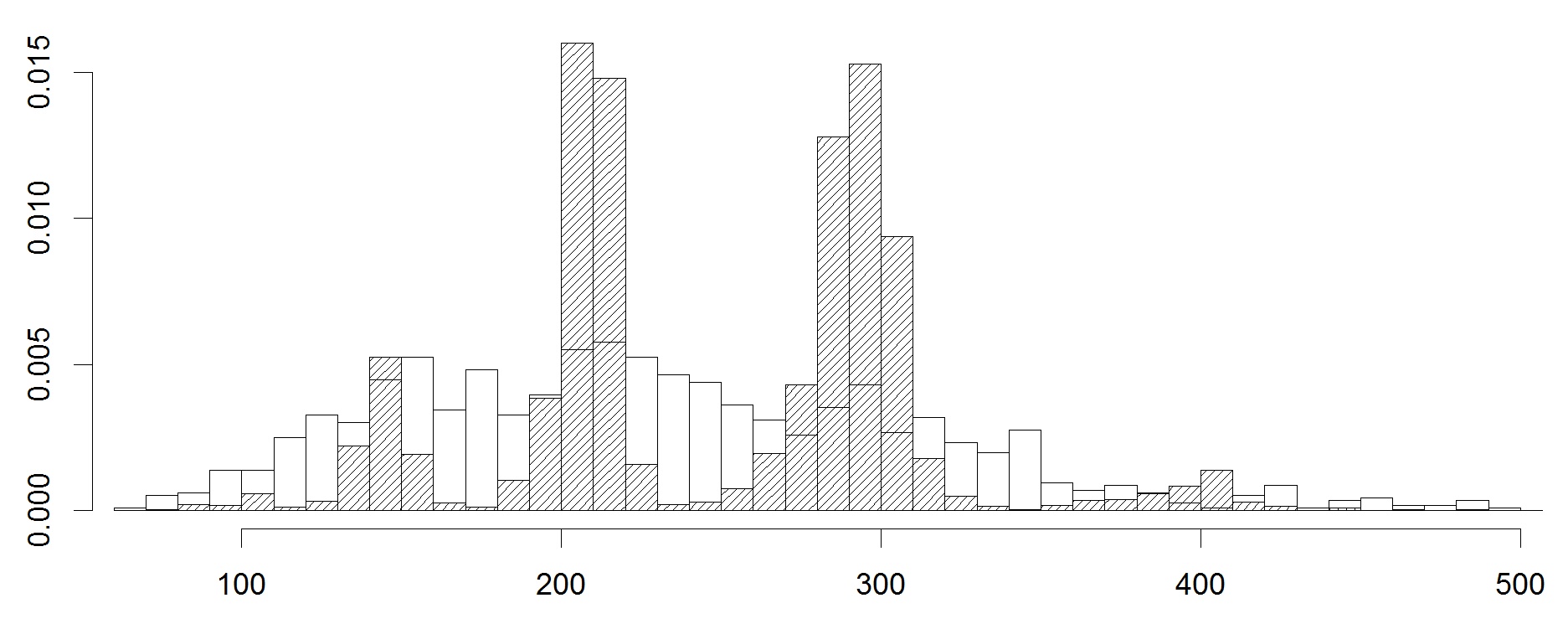

Race and Lineage among early Latter-day Saints

Race is an incredibly sensitive topic, but it is also an incredibly important topic to discuss and understand. A number of important books have been published about the racial narratives that were adopted by early members of the Church in recent years, including Max Perry Mueller’s Race and the Making of the Mormon People (The…

-

Revisiting Sherem

Many of my choices in books this year have been influenced by a decision to try and catch up on literature about the Book of Mormon. I feel a bit overwhelmed, to be honest, since there’s a lot out there and I have been more focused on the New Testament in recent years. I recently…

-

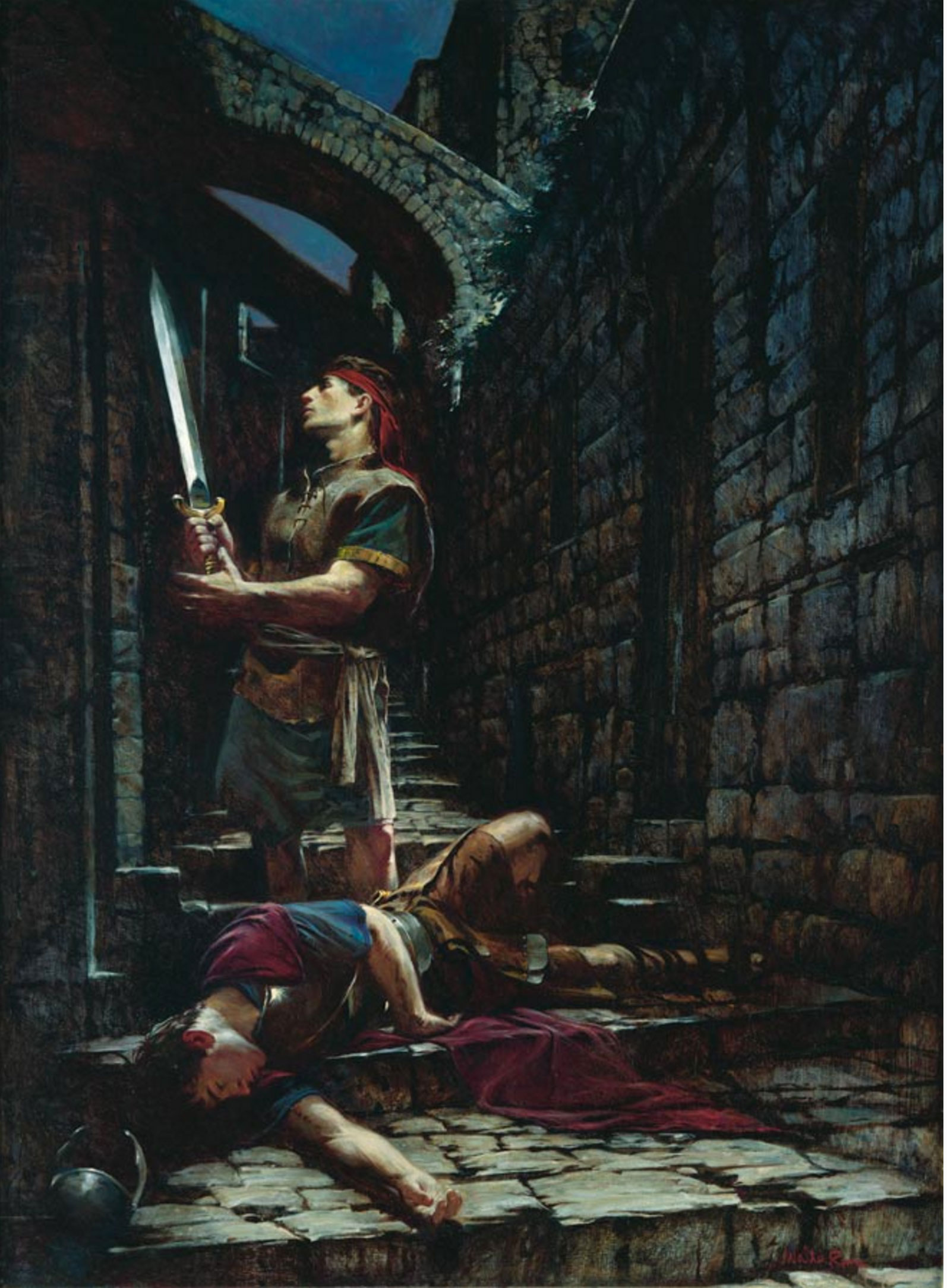

Laban… as a Christ Figure?

This Holy Week I’ve been monitoring my employer’s livestreamed Roman Catholic masses and services, meaning that I (for the first time) attended a Holy Thursday mass and a Good Friday service. So it happened that, during the reading of the Gospel of John in the Good Friday service, I noticed something peculiar. In response to…

-

Resurrection and the Timing of Healing

Bear with me as I go out into the theological weeds to explore an obscure doctrinal debate about the resurrection. As my wife and I studied the “Come, Follow Me” curriculum section on Easter, we discussed Amulek statements about the resurrection in Alma 11. Our question was: What exactly does it mean to “restored to…

-

The Way and the Ancient Gospel

Along with “baby Yoda” memes, Disney’s Mandalorian made two phrases trendy: “This is the way,” and “I have spoken.” Being a Star Wars fan, the phrases quickly made their way into the lexicon of my household. So, it was humorous to me to find an entire lesson in “Come, Follow Me” this year entitled “This…

-

Notes on the Book of Abraham

I’m only a translator in the sense that people keep paying me to translate things for them.

-

The Olive Tree Restoration

There have been some common underlying themes to several Times and Seasons posts these past few months. The three themes or questions that I have in mind at the moment are: “What is the nature of the Great Apostasy?”, “What is the nature of the Restoration?”, and “What is the relationship of the Church of…

-

Embracing Jacob’s Sermon

One of the more awkward moments of my time in graduate school came when I was reading a book about Mormon polygamy while taking a break in the lab. A visiting scientist from Pakistan who was doing research in the same lab saw me reading the book and asked me: “That looks like an interesting…

-

Sacrament Prayers and the Doctrine of Christ

I am always interested in seeing how ideas grow, develop, and take shape of the years. I suppose that is part of why I find the study of theology so interesting. As I was studying the “Come, Follow Me” curriculum this last week, it struck me how the sacrament prayers seem to have developed and…

-

The Crux of Historicity

For all their differences, the essential and irreducible historical dilemma of the Old Testament, New Testament, and Book of Mormon is very much the same.

-

What Has Isaiah To Do With Nephi?

In the neighborhood where I grew up, there was a yard that had landscaping that baffled me. It was a grassy plain with a few small trees, and then about a half-dozen boulders scattered among the grass. The boulders were what baffled me—they didn’t seem to fit in with the landscaping around them and they…

-

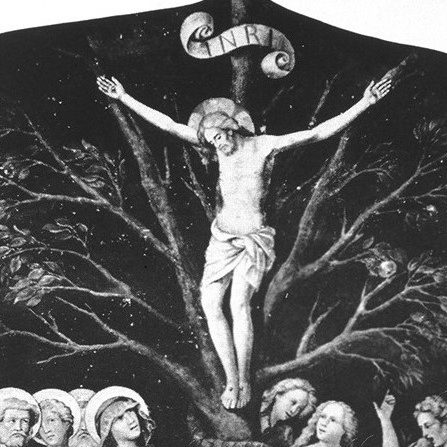

Reflections on the Tree of Life, Part 3: Christ and the Tree

The tree of life and its fruit mean many things to many different people. Immortality, eternal life, the presence of God, and Jesus the Christ are all important meanings of the tree in our tradition, but many more could be stated. Among Christians, one prominent meaning of the tree of life is as a symbol…