Author: James Olsen

-

Revelation’s Demand for More Revelation – Reading Nephi – 15:1-11 part I

More contrasts between Nephi and his brothers—although this passage strikes me as less political…and more intimate and personal.

-

The Hermeneutic of Revelation: There is Always More – Reading Nephi – 14:18-30

The end of the narrative of Nephi’s grand vision is to point beyond the vision and beyond Nephi.

-

Binaries of the Lamb and the Devil – Reading Nephi – 14:8-17 part II

I feel somewhat affronted by the angel’s adamant declaration and insistence on the binary nature of humanity.

-

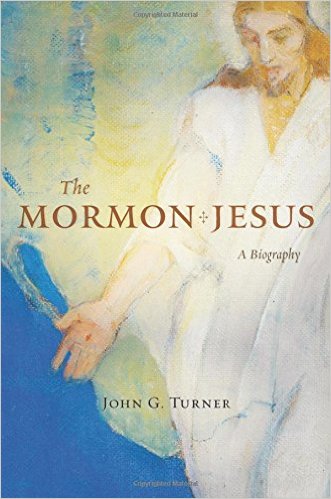

Book Review: The Mormon Jesus

I remain fundamentally unconvinced of the book’s central claim and argument, and am personally ambivalent about it—though in that I’m surely in the minority amongst Mormons (rank-and-file and all the rest) whom I suspect will heartily cheer the book’s primary claim: Mormonism, taken as a whole in it’s historic trajectory, is patently Christian.

-

Reading Nephi – 14:8-17 part I

The angel begins by reminding or interrogating or raising the covenants of the House of Israel. I’m not sure the angel’s intent. Is this pedagogical priming? Is it interrogation? Is it a test, with the angel serving as guardian or gate-keeper, not allowing Nephi to pass on to the next part of the vision until…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:42-14:7

We return now to the grand parallel Nephi makes in the articulation of his vision—Lehite afflictedness and Gentile blindness. While this passage focuses on the binary possibilities for the fate of the Gentiles, in the context of the parallel there’s a critical message for the Lehites as well—if the Gentiles can assuredly repent, then the…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:38-41

Theses passages are tremendously challenging. On the one hand they insist on the historical nature of their prophecies—an understanding of history and of God’s movement in history is their whole raison d’etre. But even retrospectively it’s difficult to get much traction, to pin down events or movements or historical happenings, or to see these passages…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:30-37

Verses 30-33 give the logic of this vision. There’s a grand parallel going on between the dramatically afflicted and nearly destroyed remnant of the Lehites and the “awful blindness” of the Gentiles. God’s ultimate covenant with Israel is rich enough to offer provisions to both in their different but analogously wretched lots. While I find…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:20-29

After successfully subverting the lands and economies of the natives and then violently refusing to remain party to their political contracts with their countries of origin, Nephi now sees the new immigrant population prospering. What does it mean that they prospered? I immediately think of things like infant mortality and economic growth. What would Nephi…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:10-19

I wonder what we’re getting here in this passage. How much of this is straightforwardly the details of the vision? In particular, is Nephi’s understanding of the vision a part of the vision, in the same way that one comes into a dream already comprehending the background and meaning of the events that one dreams?…

-

Reading Nephi – 13:1-9

A consistent feature that distinguishes the Book of Mormon from the Bible is its pan-human focus. Nephi does not strike me as very cosmopolitan—rather the opposite. He cares about his family and posterity, and his overriding focus even there is not love and loyalty but theology; he cares that they’re tied into God’s covenant with…

-

Reading Nephi – 12:13-23

The pattern goes from “normal” chaotic, difficult, mortal life, to intense trial and darkness, to the burst of light when God comes and establishes an order that results in Zion, to apostasy from Zion leading to apocalyptical violence. Interestingly, however, the apocalypse isn’t the end here; rather it’s followed by more everyday, mortal struggle before…

-

Reading Nephi – 12:6-12

And here it is, the climax of the whole story. God himself comes down from the heavens to visit his people. Note that this is how we always experience that singular (even if repeated) event: it’s in the future. We’re always waiting for the parousia and never ourselves experiencing it.

-

Reading Nephi – 12:1-5

Now Nephi looks and beholds the future of his posterity and people. And one can understand why he comes out of this vision depressed and feeling sorry for himself—and why he immediately lays into his brothers with a condemning despair.

-

Reading Nephi – 11:26-36

Behold the condescension of God. Earlier, the angel asked Nephi if he understands it, and Nephi admits that he does not. Now the angel tries to show him. But what is it that Nephi sees? First is the mere fact of the Redeemer going forth. I’ve often heard it interpreted that the condescension is actually…

-

Reading Nephi – 11:24-25

The most powerful connection for me in all of this . . . is the striking fact that the point of the word of God is to lead to the love of God. This is surely the chief constraint on any scriptural hermeneutics.

-

Reading Nephi – 11: Hermeneutic Interlude

This whole vision, stretching over the next few chapters, is difficult; I’d say downright oblique.

-

Reading Nephi – 11:13-18

As commanded, Nephi looks, and what does he see? Interesting that the first thing he sees is cities, including Jerusalem and then Nazareth. What are the other cities? Why does he see cities? This is all in the context of Nephi being guided to come to understand the meaning of the tree. Ultimately Nephi determines…

-

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: Mormons and Modernism

Mormons and Modernism: Modernism, Secularism — and the Mormon Response? Thinkers as diverse as Charles Taylor, Marcel Gauchet, John Milbank, Mark Lilla, and Louis Dupré have written about the origins of the modern period—the radical change in thought and society from the medieval period to the modern that occurred gradually and culminated in the sixteenth century. Modernism brought us the renaissance,…

-

Reading Nephi – 11:8-12

The first conspicuous element here is the replacement of Lehi’s test or opening—all that time walking in darkness—with Nephi’s being questioned by the angel. Nephi does not walk in darkness—his vision begins, after the opening angelic interchange, with looking directly on the vision of the tree. And this too is different. Lehi’s dream was experiential;…

-

Reading Nephi – 11:1-7

I’ll confess, I feel a mixture of serious disappointment and jealousy as I’m struck by the utterly exotic nature of this event. Note not only the coming of the angel, but that the angel does not come to Nephi for specific reasons of instruction or witness—not like the shepherds abiding in their fields or Joseph…

-

Reading Nephi – 10:17-22

Nephi does it again right at the start of this passage, though this time it’s in reverse: he talks about faith in the Son of God, and then realizing that his reader would need clarification on that, he inserts the parenthetical about the Son of God being the Messiah of whom Lehi had been prophesying…

-

Reading Nephi – 10:11-16

At the end of this section Nephi notes that there were many other prophecies of Lehi, and many of those prophecies Nephi wrote in his other plates. Here he’s only written what he thought appropriate. Well then, what has he written? Out of many prophecies, what does Nephi consider worth including? Two main things. First,…

-

Reading Nephi – 10:1-10

The first lines go right along with the confusion and different worldview conspicuous in 9. Having just stated the Lord’s intention for Nephi to focus on the spiritual as opposed to the secular and his own confusion over this point, Nephi launches in to tell us about his journey, his reign, and his ministry. It’s…

-

Reading Nephi – 9

This is an extraordinarily odd chapter—and odd in ways that really do support the either prophet or genius narrative of Joseph Smith. Why, if one were simply trying to cover up their mistake in losing 116 pages and the first several hundred years of history, would you stick this chapter in here? You go ahead…

-

Reading Nephi – 8:29-38

The folks who make it to the tree via the path-rod fall down. Its exhausting. This seems so significant, and seems to confirm my earlier reading of the path-rod as not the optimal means of getting to the tree; we ought not kid ourselves about the cost of this route. Likewise, there seems to be…

-

Reading Nephi – 8:23-28

Why didn’t Lehi and his family ever see or need the rod of iron or the path when they journeyed to the tree? And by contrast, why did so many of those who sought after and obtained the path & rod, then fall away? Reading closely, it is only those who relied on the rod…

-

Reading Nephi – 8:13-22

There are patterns here in the partaking of the fruit: self, then family, then others; self, then the righteous, then the wicked; self, then one’s people, then others. Enos later repeats this pattern in his great prayer. I don’t think this pattern lends credence to an egoistic (or even a growing enlightened self-interest) interpretation, however;…

-

Reading Nephi – 8:9-12

How did Lehi know that the fruit was desirable to make one happy? Usually in dreams we just know things; we know the context or the background that makes the dream sensible. Is that what it was? What about in life? Why do some of us simply know how to be happy and others don’t?…