I am going to take advantage of permablogger privilege to address a historical demography myth/pet peeve of mine which, while seemingly orthogonal, does connect to the gospel, just give me a second to get there.

There is a widespread belief that in the past children were a net asset to your wealth, and people are having fewer children now simply because they detract, and don’t contribute, to your bottom line financially, when the fact is that children have almost always cost more money than they bring in. So the decision to have and raise children taps into something more than creature comforts, and was deeply embedded in our history and genes long before birth control.

The gold standard for gleaning conclusions about the lives of our ancestors is to observe current hunter-gatherer populations. Yes, it has its issues, but it’s the worst methodology except all the others. And what does that literature say? I’ve pasted some studies and their take-aways below. Basically, the idea of the teenager living with their parents eating their food and not really contributing to society is not just a 21st-century, developed-world phenomenon, but has always been with us.

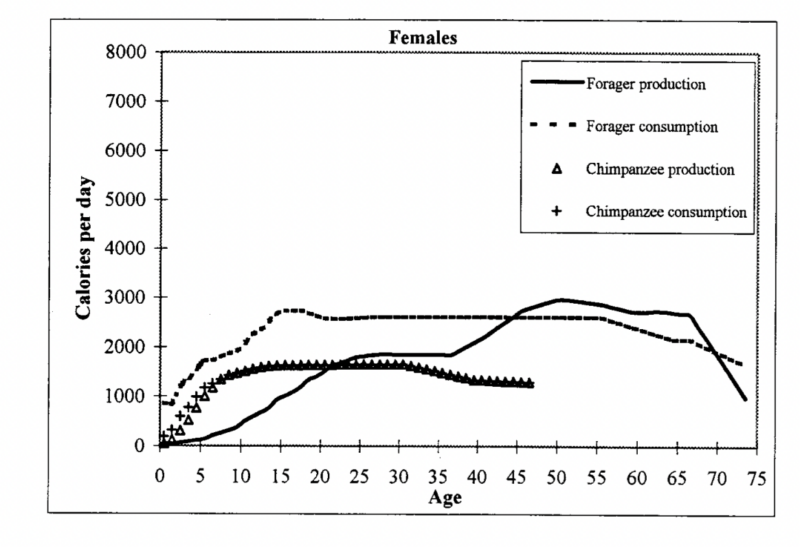

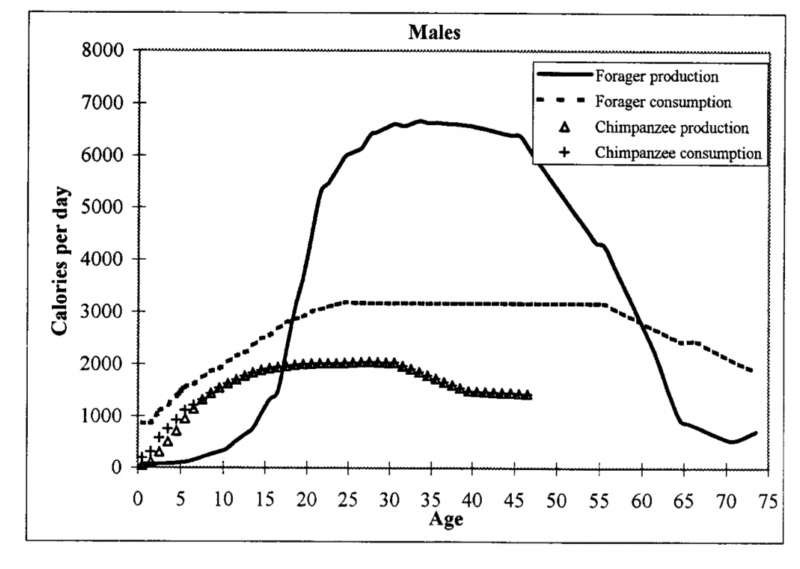

Also, as a sidebar, hunter-gatherer in this case men also produce many more calories than hunter-gatherer women. So, while I’m glad that women too have the right now to sit in an airless cubicle all day (while gender equality in the workplace is important, it has always been ironic to me how much some ostensibly left feminists glamorize capitalist work), the idea that probably the most controversial clause in the Family Proclamation: “by divine design, fathers…are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families. Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children” is an artifact of modern-day capitalism and 1950s western gender norms is also wrong. A lot of societies have that gendered division of labor. (And yes, there are some societies where the foraging women harvest as many calories as the hunting men, and some societies where a not-insignificant number of children participate in hunting).

But what do caloric surplus trajectories have to do with the gospel? One reaction to the past as-a-golden-age model is the equally wrong idea that concern for our children and the desire for progeny for their own purpose a la Abraham is a modern-day invention. It denies the naturalness and ubiquity of the generative impulse and desire for kinship and ties across time and space that, channeling Bushman here, forms the kernel of Latter-day Saint marriage theology.

Similarly, the idea that family planning is new is also wrong. They could, and sometimes often did, simply kill their infants. If Tuck Tuck the Cavewoman living in France wanted to have a independent, unattached life and enjoy all the fruits of her own labor, she could choose that lifestyle like the 40-year old confirmed bachelorette today (if she survived the unwanted births, admittedly).

People chose to keep their children for the same reason we do, and we should be skeptical when cynics imply that something as divinely central as the generative impulse and kin relation is an artifact of modern-day living.

A brief caveat, while 99% of our evolution and existence as a species happened in a hunter-gatherer context, the age of net caloric surplus is lower for agricultural societies and (more arguably) for early industrial societies when kids could take on low-skilled manual labor in the factories and such. However, for agricultural societies this simply shifts the curve about a decade to the left, so even if by the time they leave the nest they technically have a net surplus, once you take into account the opportunity cost of early infant-raising plus the chance that they’ll die anyway, having large families to be your personal agricultural serfs wasn’t some pathway to riches. It required the kind of norms and values about children and offspring per se that pronatalist cultures and theologies, including ours, promote and celebrate, even as the long schlog of evolution has literally deeply embedded them in the fibers of our being.

********************

Kaplan, Hillard. “Evolutionary and wealth flows theories of fertility: Empirical tests and new models.” Population and Development Review (1994): 753-791.

The results for the Machiguenga (Figure 1) show that children consumed many more calories than they produced during the period from birth to age 18. The average child under the age of 18 consumed 2120 calories per day but produced only 500 calories, or 24 percent of his or her total caloric consumption. Thus, while the average child consumed close to 14 million calories before age 18, he or she produced only a little over 3 million, yielding a net deficit of 10.5 million calories to be provided by adults.Machiguenga adults, on the other hand, produced some caloric surplat about age 20 and continued to produce more calories than they consumed into old age. Even after age 60, the average adult produced about 4600 calories but only consumed around 2500. Results for the Piro (Figure 2) parallel the Machiguenga data. The average child consumed about 2300 calories per day and produced only 370, for a net daily deficit of 1970 calories. For the first 18 years of life, children cost about 13 million calories in excess of what they provided. Piro adults were also quite productive into old age. The average adult over age 60 produced some 6600 calories but consumed only around 2500. The Ache did not differ substantially from the Piro and Machiguenga (Figure 3). On average, children consumed 2500 calories and acquired about 560 calories, or about 22 percent of the total. For the period from birth to age 18, the net deficit for children was about 13 million calories. Women produced fewer calories than they consumed at all ages, but men produced more than they consumed until about age 60. Old men (over age 60) in our sample produced an average of only 800 calories per day even though they probably consumed quite a bit more.

Gurven, Michael, Hillard Kaplan, and Maguin Gutierrez. “How long does it take to become a proficient hunter? Implications for the evolution of extended development and long life span.” Journal of Human Evolution 51, no. 5 (2006): 454-470.

Tests based on observational, interview, and experimental data collected among Tsimane Amerindians of the Bolivian Amazon suggest that size alone cannot explain the long delay until peak hunting productivity. Indirect encounters (e.g., smells, sounds, tracks, and scat) and shooting of stationary targets are two components of hunting ability limited primarily by physical size alone, but the more difficult components of hunting—direct encounters with important prey items and successful capture—require substantial skill. Those skills can take an additional ten to twenty years to develop after achieving adult body size.![]()

Kaplan, Hillard, Kim Hill, Jane Lancaster, and A. Magdalena Hurtado. “A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews: Issues, News, and Reviews 9, no. 4 (2000): 156-185.

Comments

5 responses to “Did People Have More Children to Work the Farm?”

It would be interesting to see studies specifically for agricultural societies, since that’s the case usually brought up. But (as you say) this is something that gets repeated so often that I never thought to question it.

Spencer, thanks for this. I was educated with the presumption that children were a net benefit to run a farm. It’s helpful to see some actual data. I do think one other key benefit exists for adults who have children (in particular men) which the data bears out but isn’t addressed in this post. More children increases the chances for a long life. The data supports the deuteronomic instruction to honor one’s parents that your days may be long.

Will you also continue this post to consider the stark differences between today’s technology and society compared to pre-modern circumstances? As important as historic caloric production data are, the data also shows universal drops in birth rates as a result of the expansion of women’s agency via contraception and education. The calorie production charts of today’s industrialized society I expect are completely different from the historical ones.

Simply put, due to advances in healthcare, infant mortality, and contraception, women can provide a replenishment level of children on their own and support their caloric needs and those of their children without any support from a man. I believe men can play a crucial role to improve lives of women and children, but that effort goes well beyond providing calories. If men’s roles are limited to those in the proclamation men will ultimately be unnecessary.

Thankfully we have the example of a male role model – the savior – whose primary work was to nurture, not provide, protect, or preside. Our hope lies in raising men to do all things good, foremost to nurture.

Good point Dave K, the fact that parents live longer (e.g. https://jech.bmj.com/content/71/5/424 ) is another important point with honoring your parents that your days may be long. That connection had never occurred to me before.

“The calorie production charts of today’s industrialized society I expect are completely different from the historical ones.” Of course, we could “produce” thousands upon thousands of calories if we wanted. Although it is intriguing to me that the amount of education that is required to be a proficient hunter actually tracks quite well with how long we keep adolescents in high school.

“Simply put, due to advances in healthcare, infant mortality, and contraception, women can provide a replenishment level of children on their own and support their caloric needs and those of their children without any support from a man.”

Agreed, although our 21st century lifestyle requires more than the wooden shack and the few handfuls of rice/loafs of bread that our ancestors had. But yes, fatherhood is obviously a lot more than just providing calories.

One thing I learned from the most recent Freakonomics episode was that 16th century England and France were having the exact same arguments. https://freakonomics.com/podcast/why-arent-we-having-more-babies/

There would be a generation of handwringing over too many mouths to feed, to the next generation of the population is dropping and we can’t support an army should we be invaded, we need more babies.

this is much simpler—birth control was not as easy as it is today.