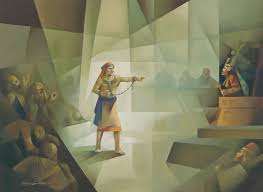

While I don’t know if Abinidi and Limhi knew of each other, I think it’s likely that they did. Abinidi is, of course, known for his parrhesia before King Noah, and Limhi is Noah’s son, who succeeded him and whose later comments indicated that he knew his father was doing evil. Today, most of the time, we focus on Abinidi more than we do on Limhi. We admire the courage that he had to speak up even though he knew that his life was threatened.

But what about Limhi? Was he of age when Abinidi called Noah, his priests, and his people to repentance? Did he say anything? Did he witness what happened?

The record is silent on this question. Maybe Limhi was too young to be involved. Maybe he was kept separate from his father and the court, and wasn’t involved. Or, more likely it seems to me, maybe he was the son of the King and with that privilege didn’t think too much about the things Abinidi said—until he was put in the place of having to rule his people and deal with the Lamanites who had conquered them.

Let’s look a little closer. Abinidi stands before Noah and calls out his evil-doing even though he has no power—even though he his vulnerable. This courage is admirable, but was it wise? Noah didn’t listen to what he said, and didn’t change. And the vast majority of Noah’s priests were apparently not reached by Abinidi’s words. Should he have said something different?

Maybe. Or maybe Noah and his priests weren’t the audience for his speech. The sermon was very effective for one of the priests, Alma, who made a radical change in his life. For him this was the sermon needed. And there may have been others who heard what Alma said and joined Alma or perhaps joined those who eventually rose up against Noah.

In contrast, we only hear about Limhi much later. If I’m right that Limhi was old enough when Abinidi gave his sermon and had access to his father, can we blame Limhi for not saying something? Everything he knew was grounded on his relationship with his father. Saying something meant loosing everything. And if he was an adult, challenging his father would likely mean death. But failing to act, to do something, makes it seem like Limhi is complicit in his father’s evil.

Limhi’s potential death for speaking up to his father may have been worse for his people, who would not have had his righteous leadership later. It seems likely that Limhi watched, listened and learned—witnessed if you like—so that his people would benefit later. Instead of the present audience of the time when Abinidi spoke, Limhi’s audience was a future audience, one after Noah’s death who would need his witness to suffer through the rule of the Lamanites and know how to flee when the time came.

So, how does this apply to us today? When do we call out the evil around us? When are we complicit in that evil? And when should we be witnesses of that evil against a future day?

I have been pondering about these roles for quite a while, and I was particularly inspired by the questions brought up in Melissa Dalton-Bradford’s Dialogue Sunday School lesson this past Sunday. She mentioned as part of her lesson the difficult choices faced by religious leaders in the Weimar Republic in the 1930s, where the choice was between parrhesia, witnessing, and complacency, or more specifically, to what degree and how to speak up.

I’ve come to the conclusion that the most important concern when speaking up is how we speak up. In politics the gut reaction is to protest—and I think that has a place. But protest has a reputation for anger, threatening actions, destruction of property, injury and sometimes even death. How it’s done is as important as who the protests are against. While protest brings problems to the attention of a wider audience, sometimes violence is either committed by the protesters (think January 6th) or by the police or counter protesters (think Charlottesville, or too many of the recent Black Lives Matters protesters, or the Edmund Pettus Bridge). And with today’s media assessing the blame for who was violent often becomes siloed by political belief.

Parrhesia, aka speaking truth to power, is likewise fraught. It can involve pleading, suggestion, criticism and even personal attacks. If the message isn’t strong enough then it is easily dismissed, but if is too strong, it’s ignored as biased—so the line between requesting or insisting on change and attacks is very thin. [Look at the recent case of Bishop Mariann Budde, whose nominally inoffensive remarks were simply requests, but were taken by many as criticism.]

Then there is bearing witness to what happened. The obvious problem with this approach is that it gives up on the present—it’s a kind of complacency, or at least an abandonment of the present in favor of a future audience. To witness means to some degree that you have to stand by and watch evil, preserving your own life so you can eventually communicate what happened. And today, with the media we have currently, isn’t testimony about what happened already being spread as soon as events happen?

I don’t know which of these roles are most important. And maybe we all need to be ready to do any one of them, depending on the circumstances. We may even have to do all three. The difficulty is first in deciding what to do under the circumstances we face, and then in deciding how to do it in a way that follows the gospel, that is the most like what Christ would do that we can manage.

However, it is clear that there is one thing we should not do. If it’s true that “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing,” can we really remain complacent? Can we really not do anything?

I think Dalton-Bradford used the example of the Weimar Republic on purpose. We are at or are rapidly approaching a point where the risk of complacency is similar. When a Maryland man is deported to a foreign jail and the President refuses to get him back, despite an order from the Supreme Court, who is safe? When MASKED ICE officers unnecessarily seize an unarmed and non-violent woman off the street, without bothering to inform her that her visa had been revoked, how is that not like the SS? When the government willfully ignores the constitution, ignoring laws passed by congress and stealing powers given to the legislature and the courts, is complacency really an option?

I hope we can figure out how to act in the face of the current evil that has taken over our government. Whether we use protest, parrhesia, or act as witnesses, we are reaching the point where we must act. Ironically, Goldwater’s immoderate statement that “Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice. Moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue” seems like it will end up being the opposition’s rallying cry—despite the violence and discord that might imply. There are better ways of acting. Instead, I hope that the oft-discounted claim that the Elders of the Church will save the constitution from hanging by a thread will be soon instead of in some unnamed future, and prescient instead of mythic.

Comments

26 responses to “Abinidi or Limhi?”

Abinidi is a great case study. I frequently find myself wondering where our Abinidi is. But then I realize that I am asking the wrong question, which is “Where is our Alma?” Not the guy who got burned to death, but the guy who actually rebuilt Nephite society. I will concede that there is no rule that says a counterpart to Alma will necessarily emerge, but if I’m going to keep getting out of bed in the morning, I have to believe that one will. So, as you imply above, I have come to believe that Abinidi’s primary purpose was not to deliver a sermon that Book of Mormon readers could dissect for gospel understanding, nor to motivate us to engage in futile but suicidal acts of resistance, but simply to awaken Alma.

(Over on Roger Terry’s blog, he points out that if we were to take Abinidi’s preaching at face value, we would be modalists and baptism for the dead would not exist. I respond with the “awakening Alma” alternative.)

So my point is that without an Alma (and keep in mind that Alma was an insider), Abinidi would just be a noble failure. So we have to wait on Alma.

In the meantime, the resistance cannot be passive, as you point out. It must be nonviolent, but nonviolence and passivity are very different concepts. We cannot shy away from an Edmund Pettis Bridge scenario because we fear blame for the violence will fall on us. Alma may be on the other side of that bridge. That scenario might be what changes his (or her) heart. That’s what worked for Gandhi. That’s what created the anti-Nephi-Lehis. We need to be mentally prepared for that scenario.

Finally, our resistance has advantages that were not present in the Weimar Republic. Hitler had the advantage of a country in such bad shape that his promises to fix things were realistic. Our president likes to whine about how horrible things were under his predecessor. But inflation never even hit double digits, much less required the printing of billion-dollar bills. (My grandfather brought the German equivalent home from his mission, if you don’t believe me.) The French were not illegally occupying part of our country. It should be much easier to convince people who thought that it couldn’t get any worse that it can actually get much worse (as it will). As I see it, the president’s dreadful economic ideas are a blessing in disguise because they will quickly demonstrate to the convincible (which excludes about 1/3 of the country) that they made a mistake. The numbers will turn in our favor unless we let our frustration get the best of us.

>When a Maryland man is deported to a foreign jail and the President refuses to get him back, >despite an order from the Supreme Court, who is safe?

The Supreme Court’s full order, dated April 10 2025, can be read online, and I have linked it below. I would encourage you to read it and contrast what you see with the inflated coverage (frankly histrionics) bouncing around the Internet. The Court’s formal opinion, joined by all 9 justices, is only three paragraphs long, and easy to parse. For convenience, I will reproduce the ENTIRE section governing remedies, ie what the Government is obligated to do.

“The application is granted in part and denied in part, subject to the direction of this order. Due to the administrative stay issued by THE CHIEF JUSTICE, the deadline imposed by the District Court has now passed. To that extent, the Government’s emergency application is effectively granted in part and the deadline in the challenged order is no longer effective. The rest of the District Court’s order remains in effect but requires clarification on remand. The order properly requires the Government to ‘facilitate’ Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador and to ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador. The intended scope of the term ‘effectuate’ in the District Court’s order is, however, unclear, and may exceed the District Court’s authority. The District Court should clarify its directive, with due regard for the deference owed to the Executive Branch in the conduct of foreign affairs. For its part, the Government should be prepared to share what it can concerning the steps it has taken and the prospect of further steps. The order heretofore entered by THE CHIEF JUSTICE is vacated.”

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24a949_lkhn.pdf

First, the Supreme Court itself dismissed the deadline for the Government to take action. Second, it REMANDED Judge Xinis’ (the judge handling the case in the Maryland District who ordered the Government to “facilitate and effectuate” Abrego Garcia’s return) order, asking her to clarify what she meant by “effectuate,” because it may exceed her authority. The Supreme Court’s reference to “the deference owed to the Executive Branch in the conduct of foreign affairs” highlights where they think the problem is: there is longstanding precedent in the United States that Article III courts (the Supreme Court and all the district and circuit courts) have no jurisdiction regarding the President’s execution of foreign affairs.

Note that the Supreme Court does NOT require the return of Abrego Garcia to the United States. It requires the Government to “facilitate” his release from custody in El Salvador and the handling of his case as it would have been had he not been removed to El Salvador. That does not require his re-entry to the United States, as we can handle immigration appeals without the immigrant returning to U.S. soil. The part of Judge Xinis’ order which the Supreme Court wants clarified is precisely the part where she orders the Government to “effectuate the return of…Abrego Garcia to the United States.” The Supreme Court avoids any endorsement of that part of the order and requests clarification.

Lurking in the background is the fact that, since deportation is a civil issue, the U.S. cannot extradite Abrego Garcia for criminal proceedings, and statute otherwise bars him from entering the country. This “Maryland man,” as you put it, is not a legal permanent resident or citizen – he is a national of El Salvador found by immigration courts to be subject to removal from the United States with no right of reentry. The wrong that was done to him – which the Government admits – is not that he was removed from the country. His asylum claims were denied by an immigration court and his claim under the Convention against Torture was also denied since he expressed no fear of the El Salvadoran government and the CAT doesn’t cover gangs or cartels. The only claim granted him was a Withholding of Removal to El Salvador because he claimed to fear a local gang there. If he had been deported to, say, Belize, he would have no legal standing to complain. And since deportation is a civil proceeding, it is against statute to just bring him back and redo the process.

Don’t get me wrong, the Government admits it erred in sending Abrego Garcia to El Salvador specifically owing to his Withholding of Removal finding. I do not assert the innocence of the government, but it is far from clear (a) that the proper remedy is returning him to the United States and (b) that the court could order such a remedy even if it were proper. An Article III court is not a “man under authority” a la Matthew 8 – it can’t just say “go”, and the State Department goeth, or “do” and DHS doeth. There are specific remedies it can order and others it can’t, and the court cannot require remedies beyond its powers regardless of the merits of the situation. We call those situations “non-justiciable cases” – the remedies are beyond the court’s constitutional power to grant.

In response to the Supreme Court’s order to clarify, Judge Xinis deleted the word “effectuate” from her order, requiring instead that the Government “take all available steps to facilitate the return of Abrego Garcia to the United States as soon as possible.” Note that she simply deleted the troublesome word “effectuate” but attached the approved word “facilitate” to things it did not previously embrace – the Supreme Court nowhere affirmed the necessity of returning Abrego Garcia to the United States. In so doing, she has still left her order too vague to ascertain if she has stepped beyond her powers, into requiring the Government to break a statute or take actions with regard to foreign relations. “Facilitate” – to make easier or enable – is not exactly “bring him here now by hook or by crook” especially where the district court runs the risk of overstepping lawful Article III powers or ordering the Government to break statute.

In response to this deliberate vagueness, and in the absence of any deadline (remember that the Supreme Court eliminated the deadline, which was replaced only by “as soon as possible”), the Government appears to have interpreted Judge Xinis’ order to “facilitate” as removing any domestic barriers to Abrego Garcia re-entering the U.S., which is pretty easy as there weren’t really any within its discretion. Abrego Garcia can’t re-enter on his own according to Congressionally-passed statute, he can’t be extradited because there are no charges pending (is the court going to require him to be charged with a crime in order to get him back here? beyond its power), and he is not in custody in a U.S.-controlled facility. Article III courts cannot command the President to pull a foreign head of state aside and ask him to release a prisoner – that would be trespassing on the “deference owed the Executive Branch in the conduct of foreign affairs,” as the Supreme Court put it.

So, after that lengthy digression into legal technicality which maybe 5 people will read – your one-sentence framing of the situation elides the actual complexities, the push and pull of Article II and III of the United States Constitution and associated precedents, and the endurance of the Constitutional order. The White House has not declared itself free of the Constitution. It has not defied a Supreme Court order. It has, admittedly, played cute with the interpretation of a vague lower court order – which the Supreme Court also wanted clarified, and which was not substantially clarified at all.

I thought I would drop this clarification since I happen to be familiar with the topic at hand and, frankly, the situation is both less dire and more complicated than your sources appear to have represented.

Abinadi?

Hoosier, I appreciate the legal nuances, but let’s look at the result. A man who has been convicted of no crime is now in a brutal prison (I presume you’ve seen the pictures), apparently for life, because of the actions of the Trump administration. And they are celebrating this outcome. A court shouldn’t have to tell them this this is wrong, and shouldn’t have to order them to fix it. If a court can’t order them to fix this situation and there truly is no remedy, that’s an indictment of our laws and legal system, not an exoneration of the Trump administration.

Nor is Garcia alone. Several hundred people were sent to this prison by the Trump administration with no due process and no conviction. Garcia is only unique in that a court specifically ordered he not be sent to El Salvador. The Trump administration claims these people are all gang members, but has provided no evidence of that. Their lawyers suspect the Trump administration is simply declaring that anyone who has a tattoo–any tattoo–is a gang member.

This is wrong. If it’s not also illegal, that is wrong.

Yeah, Hoosier, a confirmed rapist, embezzler, and extortionist who was convicted by due process is not only serving zero jail time, but is denying due process to innocent people

being sent to Central American prison camps. Obviously our legal system is a farce and a fraud right now. Stop arguing what’s legal and start arguing what’s right.

In a discussion comparing the U.S. today to pre-Hitler Germany then, and possible resistance to the upcoming dictatorship, would Hoosier be cast as a brown shirt?

For all of Hoosier’s talking, what about the injustice, indeed, the crime, that the U.S. government at the highest level has purposefully and intentionally committed? And what about the victim who is languishing in the concentration camp at the expense and direction of our criminal U.S. government?

The Constitution is hanging by its proverbial thread, and where are the Elders of Israel? They’re rushing forward with scissors.

Last Lemming: Thank you.

I should point out that part of my message is that we do need all three roles. We need those, like Abinidi, who speak truth to power. We need protesters, like Alma, who gather those who can’t live under evil, and even flee when necessary. And we need those who are witnesses, perhaps those who see the evil by those who they have supported in the past, like Limhi, and who record what has happened.

What we don’t need is complacency — which I assume is what Hoosier is advocating?

Hoosier, as others have suggested, you are focusing on the leaves and ignoring the trees.

RLB, JB, ji, thank you. I agree.

And Tom, in an earlier pre-publication version of this post, I referenced a joke I once heard — to the effect that yes, the Elders would save the constitution from hanging by a thread — and given today’s politics, those Elders would clearly be Democrats…

Be careful with politicized stories. They have a way of betraying us in the end. I hope that we do right by Garcia–but let’s not fool ourselves into believing that this is first time that something like this has happened. The only reason it’s big news is because the mainstream media hates Trump.

Oof, tough crowd.

Kilmar Abrego Garcia should not have been returned to El Salvador, owing to his Withholding of Removal order. Trump should pull some strings with Bukele to get him released and sent elsewhere. However, Abrego Garcia does not have a right nor a reasonable expectation to return to the United States under the Immigration and Nationality Act, and the Article III courts do not have the power to order President Trump to pull such strings under the Constitution of the United States. I find it grimly amusing that you, Tom, think I’m going at the Constitution with a pair of scissors, when you and your confederates can’t be bothered to actually learn or apply it. You treat the Constitution like a set of vibes, not a body of law, and expect me to take you seriously while you beat your chests online about what a brownshirt I am?

Trump has not defied an order of the Supreme Court. That was what I demonstrated, and nobody actually said anything to credibly contradict it. In fact, something grimly funny happened. You didn’t contradict my assertions regarding the law at all. Instead, you all seemingly accepted them – and started saying stuff like this:

“If the court can’t order them to fix this situation and there truly is no remedy, that’s an indictment of our laws and legal system…”

“Obviously our legal system is a farce and a fraud right now. Stop arguing what’s legal and start arguing what’s right.”

Funny, all it took was a demonstration of how the law is not, in fact, being brazenly denied, to turn you all against that law! Against the Constitution’s own division of powers! That’s what “Article II” and “Article III” mean, after all – Article II and Article III of the United States Constitution, fixing the powers of the presidency and the Supreme Court respectively. And here you are, fulminating against them as morally illegitimate? The Supreme Court created and today upholds the deference in foreign affairs due the Executive. If the Supreme Court’s rulings and base of authority are so illegitimate, with what shall you replace them?

“Stop arguing what’s legal and start arguing what’s right.” Oh dear. Forget the laws, do what’s right in your own eyes! I, uh, don’t think you’ve thought this through.

Jack, this is indeed the first time something like this has happened. The reason it’s big news is because it is a betrayal of our republic, the principles behind our republic, and the rule of law — not because the mainstream media hates Trump.

Be careful of your support for a criminal and dictator.

Hoosier, you leap to some conclusions I think unsupported by the evidence.

“The White House has not declared itself free of the Constitution” – actions speak louder than word, the volume of court cases against Trump’s actions are indicative of an administration over-flexing, … oh, and as for words, statements such as, “Judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power,” seems like additional evidence of spitting in the face of the constitution, imo. But you do you..

“It has not defied a Supreme Court order. It has, admittedly, played cute with the interpretation of a vague lower court order” – All the Supreme Court asked from the lower court was to clarify the scope of “effectuate”… because how far was the lower court saying the president had to go if the foreign leader refused? Say “pretty please?” Levy tariffs? Start a war? This is where the complexity you referenced comes in. However, the Supreme Court stated the lower court “properly” required the administration to do something to return the man. By continuing to “play cute” with this order, the admin. provides further evidence of what it thinks of the rule of law.

“the situation is both less dire and more complicated than your sources appear to have represented.” – I agree with the “more complicated”statement, a fact that the administration is using to its advantage. However, you don’t provide any evidence to support your opinion regarding the direness. There is an abundance of evidence that the administration is “playing cute” with the constitution, including numerous court cases, their opinions posted on social media, and their actions. Personally, I think any branch of the government “playing cute” with the constitution is concerning.

And so does much of the world. I live overseas in a multi-national community. I have many expat friends stationed all over the world. The death spiral of the United States (and its global ramifications) is basically all everybody is talking about.

Hoosier, this would be a very different case if Garcia had simply been deported rather than imprisoned. He may have no right to be in the United States, but he does have the right not to be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. If the Trump administration has really found a loophole that allows it to deprive people of their constitutional rights without violating any law and which cannot be reversed by the courts (and note that he’s already talking about applying it to citizens), then we need to fix our laws. We fixed a lot of laws after Watergate to try to prevent someone like Nixon from abusing the power of the presidency; if democracy survives Trump we’ll need to do even more.

As for whether Trump has violated an order by the Supreme Court, we’ll see if the Supreme Court agrees with your reasoning. They haven’t responded yet. There are multiple judges in the process of deciding whether the administration has defied the courts, including one who has found probable cause that they did. Trump is taking advantage of the fact that the courts move slowly, but they’re beginning to catch up.

Jack, please don’t fall into the trap of dismissing what the mainstream media reports because of their supposed bias. That’s a ploy the right-wing propaganda machine uses to isolate people from other sources of information. When the Church added the section on “Seeking Information from Reliable Sources” to the handbook in the wake of January 6, I’m quite confident they meant to steer members towards the mainstream media, not away from it.

Hoosier, I appreciate your calm, non-catastrophic reading. There will undoubtedly be a great need for it in many ways. But Harvie Wilkinson is an experienced and respected conservative judge appointed by Reagan. I’m sure you’ve already read his full decision, but this part has gotten a lot of attention:

If Wilkinson is saying that we should be shocked, this may be one of those occasions where remaining calm is not the appropriate response.

I have to add that Hoosier’s legalisms are really distracting from the point of the post. I’m not arguing about the Trump administration’s ignoring the Supreme Court (although it seems clear that they are — that the intention of the Court’s language is to get the administration to bring Garcia back to the US, which they have said publicly that they are not doing).

No, the point of the post is that we are at the point that we need to decide how we are responding to an unprecedented level of evil in the leadership of our country. In response, are we going to protest? Are we speaking truth to power? Are we witnesses?

Or are we going to be complicit?

Kent, I think that Hoosier has ably demonstrated that the Trump administration is not defying the Supreme Court. And if they aren’t–then what is it about their leadership that is so evil?

I don’t love Trump–I really wish he’d do some things differently. But to imply that the Trump administration has risen (or fallen) to an unprecedented level of evil is an overreaction–IMO.

We are so politically divided in this country that we are having difficulty seeing past the manufactured narratives–on both sides. Did any of us even raise an eyebrow when the Obama administration rained fire from drones on terrorists–and a whole lot of innocent people?

There are other more compelling candidates for evil leadership (IMO) like losing 50 thousand of our boys in the Vietnam war and then letting Saigon fall as if their sacrifice meant nothing–let alone the horrid price that was paid by the south Vietnamese.

So let’s take a step back–and let things play out a bit lest we find ourselves pulling up the wrong stakes and causing unnecessary mayhem.

I’m trying to picture Jack standing next to me in Pershing Squre Park on Inauguration Day 1973 protesting the Vietnam War. I can’t do it.

Jack and Hoosier, it is easy to tell whose side you are on. Your loyalty to the person of your party leader is strongly evident.

For the safety of our republic, I hope history will find that you are on the wrong side.

In contrast, some (or all?) others here seem to be on the side of truth, justice, and the American way — the rule of law, and separation of powers, constitutional government, due process and fairness, and so forth. But as you would correctly remind me, elections have consequences, and your party (and your party leader) won.

ji,

As I’ve said before: I didn’t vote for Trump–but I know a lot of good people who are better than I am who did. And my estimation of you is that you are one of those who is better than I am who didn’t vote for Trump. And so my hope is that when the dust settles you and I and all the good folks out there–regardless of our individual sociopolitical philosophy–will be able to stand together with respect to our loyalty to the Kingdom.

I don’t think it’s useful to put Jack and Hoosier on the other side. I have no idea how Hoosier voted or would vote today, and most adults have at least some reservations about who they end up voting for in any election.

But, Jack, setting aside the metaphysical question of what makes a person or administration evil, it’s not hard to find examples of evil things this administration has done or is doing. Wantonly cutting foreign aid on short notice and letting children starve to death – it’s already happened – is evil. Canceling the visas of legal immigrants for no reason and with no warning and telling people with jobs and families to leave the country within a week is evil. Siding with Russia against Ukraine and trying to extort mineral rights from a country facing an invasion is evil. Threatening our closest allies with loss of territory or sovereignty is evil.

You asked: But what about previous administrations? Those administrations aren’t in power today. Trump is. He’s the problem that we have to deal with. And the people with the most responsibility to do something about the evils of the Trump administration are those good people who voted for him. It would be really helpful to hear from them right now to push back against the foreign aid cuts and dehumanization of immigrants and betrayal of Ukraine. And there are a few of them speaking up, although almost never mentioning Trump by name. But so far, they’re a tiny minority.

Jonathan,

I agree with much of what you say. But just to clarify–the reason I mention past administrations is because of the claim that this administration has risen to an precedented level of evil. And I’m not convinced of that–not yet at any rate. Surely Trump has done some questionable things–some evil perhaps and some just plain dumb. I don’t know…

But this much I know: anyone can do a little digging and find all kinds of nasty things–or at least claims of nasty things–that have been done by previous administrations. Even Reagan, the hero of the right, according to some folks, did some things that would make Garcia’s incarceration look like a walk in the park.

Oh, and out of curiosity–why the alternate spelling A-B-I-N-*I*-D-I rather than *A*-D-I?

Did Royal Skousen discover a scribal error perhaps?

Jack asked “why the alternate spelling A-B-I-N-*I*-D-I rather than *A*-D-I?”

Because I’ve never noticed the exact spelling. My bad.

As for previous administrations, I’m quite sure that the sheer volume and magnitude of the evil actions of this administration dwarfs those of previous administrations. I have been paying attention since the Nixon administration. And I was registered as a Republican from when I could vote (just prior to Reagan) until 2016, when the Republicans chose someone who I then KNEW was evil from his actions here in New York City — from his taking out full page ads advocating for capital punishment for 5 young men who the police had hounded into confessions of a crime they hadn’t done — to his abuse of companies and individuals he hired to work as contractors (who often never got paid) — to his rampant public immorality.

I haven’t seen so many actions that were widely seen as unconstitutional. I haven’t seen so many people fired with so little notice. I haven’t seen so much of the appropriations passed by law ignored. I haven’t seen so many public personal vendettas happen, where individuals, law firms, universities, etc. are attacked by one public figure, merely to get back at them. It goes on and on and on. This is NOT like previous administrations.

[Not all of these are obvious — for example, the reason that Columbia University had $400 million in grants cut is all about Trump’s attempt to sell property to Columbia years ago for $400 million. It was rejected when Columbia’s RE advisors said that the property was worth maybe $100 million. So the Columbia grants cut is at least in part a vendetta!]

If you don’t believe me, please do the research and prove me wrong. Count up the number and magnitude of what Trump has done. It isn’t even close.

Thank you for this article. I find it very well written and informative. I agree with its implications.

There are two problems with the Trump administration. One is its policy goals, as Jonathan has described. The other is its attempt to vastly increase the power of the president and indeed of the government itself, crush its opposition, and move us towards a more totalitarian state.

It has run roughshod over the other branches of government. In deference to Hoosier I’ll wait for the courts to definitively decide whether it has violated the law or defied the courts, but an awful lot of lawsuits have been filed and many preliminary rulings have gone that way. It is trying to force institutions to do its will, including universities, the media, big law firms, and state governments. And it is seeking retribution against individuals, attempting to ruin the careers of some and put others in jail.

Conservatives should realize that, unless democracy itself is ended, a Democrat will win the presidency someday. Imagine a left-wing equivalent of Trump treating churches the way Trump is treating universities, treating the right-wing media the way Trump is treating mainstream media, etc. Would that be okay? Of course not. The central bargain of a liberal democracy is that the power of government is limited, so it’s okay if people we disagree with win elections sometimes. Trump is attempting to end that bargain, but democracy cannot survive without it.