I’ve written about the implications of highly fertile, highly religious groups such as the Amish and Haredi Jewish community before. While Latter-day Saint fertility is higher than average, it’s not even close to those levels, and probably won’t ever be unless we revert back to Haredi-levels of communal insularity (or reinstate polygamy), which is a move I don’t think we should do for various reasons. Still, in some ways it’s inspiring seeing some groups buck the trend, and future, perhaps qualitative, work may shed some light on how to maintain large family sizes without having to go full Amish, who knows.

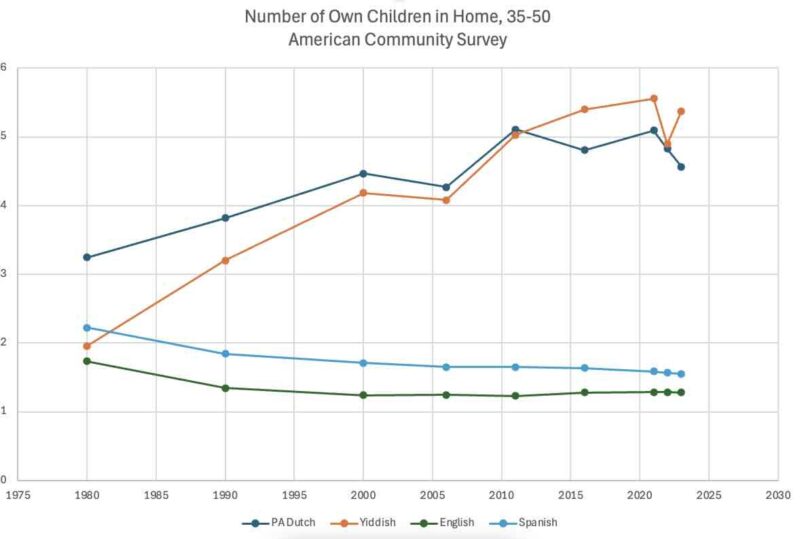

Using IPUMS Census data, I pulled the number of own children in a home, a measure that is often used as a good-enough proxy for children ever born at that age, for people between the ages of 36-50. I divided the trend lines out by language: Spanish and English, to get a more typical swath of the population, along with Yiddish speaking and Pennsylvania Dutch speaking.

The latter two languages are German-based. Yiddish is largely spoken by the Haredi community, and Pennsylvania Dutch is largely spoken by the Amish and their cousin faiths, so in the absence of a religion question in the US Census, taking language spoken at home can kind of get at some religious and ethnic communities, but it’s obviously not perfect, since the kind of Pennsylvania Dutch and Yiddish speakers who respond to US Census survey are probably more “liberal.” Also, Census data can get complex, so if I was submitting this for peer review I’d put a lot more time into those technicalities, but for our bottom-line purposes these simple estimates should work.

As seen, the Yiddish and PA Dutch languages jump around a little more, as they only have about several hundred per year in the target age demographic, but there is a clear upwards trend in family size across time, suggesting that family sizes are increasing while, as a point of comparison, the typical American’s is obviously decreasing.

One caveat, this may be an artifact of the decline in non-Haredi Yiddish speaking households or non-religious Pennsylvania Dutch households. As fewer non-Haredi or non-Amish speak these languages, the ones that still do are the more religious, more fertile groups, but I don’t have enough insider information on these linguistic communities to know how feasible this explanation is. I bounced these numbers off of a Jewish Studies colleague who does research with this community, and he said they passed the smell test, and were probably attributable to both the relative decline of non-Hasidic (both Haredi and non-Haredi) Yiddish speakers along with the increase in family sizes.

Whatever the case with the trendline, it is clear that these groups have sky-high fertility in official government data in the year 2025. There are some newer property developments that are almost exclusively Haredi, and it will be interesting to watch them as more census data comes in and we get a trend line to see how long they can maintain large family sizes in the face of modernity.

As for us, again I think the best we can hope for is maybe slightly more than what we’re pulling now. If we really dialed up the pronatalist rhetoric, which I doubt will happen given the sensitivities involved (plus I think people tend to exaggerate the extent to which General Conference talks influence people’s personal day-to-day lives and lifestyle decisions), maybe we could hit 3.5 or so.

Comments

10 responses to “Amish and Haredi Family Sizes”

I have a couple, contrary thoughts. First, it seems like in both cases, these communities have high fertility, and a linguistic border to larger society, and a religious withdrawal from society. But wouldn’t the religious community as a whole be larger (and stronger) if it also included less fertile, less secluded members surrounding the core? Or to look at it another way, wouldn’t the Yiddish and Pennsylvania Dutch language communities be stronger if they also included the less religious? Maybe an extreme degree of tension with larger society is one path to high fertility, but it seems less optimal in other ways – with less tension, you’d still have your Haredi or Amish core with large families, but also a population who were less religious and less fertile, but still present as members of the community.

The second thought runs counter to that. You don’t think pronatalist rhetoric can shift our numbers much, and I agree – but what if it was accompanied by a ratcheting up of tension with the outside world? We’ve been gradually decreasing tension with society for around 150 years, but what if there was a sharp course reversal, maybe not as far as the Haredi and Amish, but a distinct step in that direction?

To the first point, I do think the less permeable borders helps retain their strength of conviction and, ultimately, norms. The Amish can keep it up because they have a fairly strict “sacred canopy” that they control over their children. If little Ezekiel can go play X-Box with the liberal Amish next door neighbors with two kids when he’s at their house it becomes harder to insist on your own boundaries and lifestyle, but if nobody has an X-box and everybody around you agrees that you shouldn’t have X-boxes it becomes easier to enforce the norm. Perhaps another workable model is the Catholic one that has specific intentional religious communities nested within a broader religion, so if you want that level of strictness you can join a cloistered, highly bounded monastery, but you also have a more relaxed variant in general parishes, all within the same tradition.

We kind of have our version of this with missions, where we live Amish and Haredi-level strictness (if not more), and I along with many others have fond memories and lessons learned from our own 1.5-2 year stint as religious itinerants, but I’d kind of hate to do it again and I’m glad that I can read a book and engage the outside world. Of course, here the only variable is retention of norms and strength of religious conviction when there are other variables at play, and disengaging from the outside world typically includes disengaging from much that is wonderful about it such as scientific discoveries and understanding and the diversity of experiences and people, plus it makes faith more brittle when it does interact with the outside world because it isn’t prepared for it, but if policing of norms is the only variable under consideration then yes, I think the stricter boundaries does lead to that.

As far as to the second question, in terms of preferences I personally think we could stand a little more tension, but I’m having a hard time seeing a mechanism for a sharp reversal short of something big like another call for intentional communities, another physical gathering, or something like polygamy. As faith becomes more of a chosen and not inherited/cultural institution I suspect there will be a drift to more tension as selection effects start to kick in and the people who keep going to the temple are the ones who really want to go to the temple and do all that entails (I think this is why younger Catholic priests are exponentially more conservative than their elders), but this will be a gradual process.

I wonder if high fertility is commanded by God, or if it is a leftover desire from the past? Or, in other words, I wonder if low fertility is a problem that God expects us to solve?

Isn’t fertility usually measured as number of children per woman? That tends to reduce the effect of polygamy, for example.

And in that vein, I have heard that the number of children per woman was actually lower under LDS polygamy, right?

ji: There’s enough pronatalism in the canon (e.g. 132) I think I’m safe seeing the “multiply and replenish” imperative as being core and not just a false tradition of our fathers. I expound on this at greater detail here: http://archive.timesandseasons.org/2022/07/siring-gods/index.html

Kent Larsen: Higher-order wives do have marginally fewer children than monogamous wives and first wives, but at the macro level polygyny leads to higher marital rates and lower marriage ages leading to higher fertility at the societal level. I was involved in the Mormonr post on this subject that has more citations: https://mormonr.org/qnas/fX8STb/polygamy_and_population_growth

I wonder if “multiply and replenish” is an imperative? And if yes, is it (1) general guidance for humankind generally; or (2) commandment to each and every person individually?

For me, it works better to think of changing fertility rates (and marriage rates, and marriage ages, and so forth) as simply a fact of life, one of broader societal trends, rather than a matter of individual sin. As such, I am cautious about seeing lowering fertility as a problem to solve. After all, even our church’s apostles, generally speaking, are having fewer children than in old days.

It’s pretty clear–in D&C, Genesis, and the temple (more details in that link above) that it’s an imperative for humankind; whether it’s an imperative for an individual depends on their particular circumstances, but yes, barring any impediments to health, relationship status, what have you, by extension it would also apply to the individual if it applies to the society.

“Sin” is harsh, but sure, I feel comfortable saying at the aggregate, societal level that cratering fertility stems from wrong priorities (without making a judgment call about a particular individual). Fertility is getting so low now that it’s an objective problem whether you are Latter-day Saint or not. (https://timesandseasons.org/index.php/2024/10/a-shrinking-church-in-a-shrinking-world/). And finally, as far as the general authorities; I kind of don’t care how big of a family they have. Many of them with smaller families like Holland have been open about their infertility issues, and whether they’re a GA or not if they did not have an extra child so that they could make partner faster (not saying there aren’t other reasons people have fewer children) I suspect that will be a decision they’ll regret on the other side. One shouldn’t live one’s life according to inductively derived, unspoken conclusions about the work/life balance of general authorities.

For those who like to kind of thing: “The 1,471 Children of Area Seventies Considered Collectively and Not Individually” at Junior Ganymede.

link

Does anyone know the Amish and/or Haredi stance on birth control? I suspect the only way to get that high a fertility rate across a substantial population is to make birth control unacceptable or unavailable. It seems like as soon as you make it relatively easy to choose how many children you have the number of children plummets. I’m the oldest of eight children who were individually prayed about (and budgeted for) before being conceived, but my parents are exceptional in many ways.

Catholicism has some theology behind their (mostly theoretical) birth control ban (sex is inherently sinful and only justified for procreation) but we explicitly do not (“[Physical intimacy] is ordained of God for the creation of children AND for the expression of love between husband and wife” –handbook section on birth control, my emphasis) so I don’t see that as an option. I do think more pro-natalist rhetoric could make a small difference on the margins. I’d frame it as “this is something you should pray about together and follow the promptings you receive.” The further we get from the Mommy wars of the 1990s the less extraneous baggage that message will carry with it.

I don’t know about their positions, but IIR correctly based on Hutterite studies natural TFR is something like 14 kids, so any community with a TFR less than this is employing some form of birth spacing, even pre-birth control. We have a tendency to dichotomize birth control as either artificial birth control with a 99.9% success rate or no spacing whatsoever and 20 kids, when the vast majority of societies across history have clearly done birth spacing without artificial birth control. FWIW I get the sense that the Amish/Haredi attitude are more positive (kids are good) than negative (birth control is bad), and that the former attitude is more effective, as you can see from the fact that Catholic fertility isn’t any different than Protestant fertility.