A chart I ran across on Twitter that I use in my stats classes.

I don’t know if they’re still around doing their thing, but a while ago the “Black Menaces” group got some attention by interviewing hapless BYU students about different social topics in a way to try to make them look stupid and close-minded. The not-so-subtle subtext was that only those silly privileged white kids would hold conservative opinions on social issues, whereas minorities with their wisdom gained from a lifetime of discrimination would naturally gravitate to another perspective.

Like The Book of Mormon musical implying that Africans don’t worship God because of theodicy issues, these folk hypotheses don’t really hold up to even cursory examination as, for example, Ugandans actually tend to be quite religious, and plenty of African Americans hold the conservative social views the Black Menaces are mocking white BYU students for.

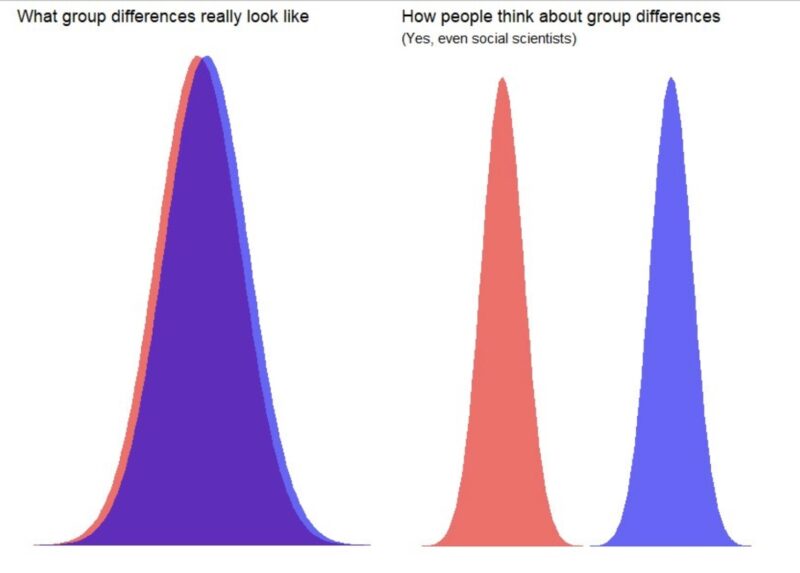

These are specific examples of the kinds of demographic morality plays you see that often take trends with a kernel of empirical truth and blow them into narratives based on demographics. For example, the gender gap in abortion is real but very small–61% of men versus 64% of women support abortion in all or most cases. Yet, these single-digit differences are then often spun into some grand demographic morality play: in one corner you have old, white men who think that women having sex is icky, and in the other you have liberated, independent young women. This group-based otherization results in the reframing of political contests into demographic clique-based civil wars.

These narratives are essential parts of grander, meaning-giving stories, so much so that people sometimes respond negatively when they are challenged. I remember as a budding wannabe political scientist attending a paper presentation at the Midwest Political Science Association in Chicago by Gary Segura, the Stanford political scientist who was one of the Hillary Clinton campaign’s primary consultants on the Latino vote and, I suspect, one of the chief ideologues for the overly simplistic “demography is destiny” narrative (the idea that immigration and increasing numbers of minorities will lead to semi-permanent democratic majorities) that allowed the Clinton campaign to become complacent. He presented results that showed that Black people aren’t any more likely to vote against gay marriage than white people once you control for religion. Dr. Segura was openly gleeful at these findings, which was curious to me. If the main metric of interest is the overall rate of approval of gay marriage across the population, then the race differentials per se shouldn’t matter, but I realized that he was only excited about them precisely because they support the Black Menaces’ narrative of white=naive and discriminatory, while non-white equals sagacious, wise, and empathetically liberal, which again is part of a larger, essential ur-narrative in modern-day progressivism that blows up the importance of empirically real but often not substantively large group differentials. Of course that’s not to say that there aren’t unique experiences that shape the white, Black, Native American, Japanese American or what have-you experience and outlook, just that interpretations of how exactly such perspectives are operationalized into political action often fit a little too neatly into partisan grand narratives.

So on to the election. As a personal aside, my oldest children and I were able to attend the official Harris watch party at Howard U. The nature of election results coming in, and their attendant psychological effects, is gradual and creeping. There was no one moment when everybody realized that they lost, rather the heaviness gradually fell upon the crowd by incremental degrees throughout the night as it very gradually became clear which way the swing states were leaning.

Anyway, the aforementioned demographic warfare narrative took even more of a beating from the election, as it is increasingly looking like a majority of Hispanic men actually voted for Trump. Anecdotally, this isn’t terribly surprising to me. I’m one of the few white, white-collar professionals on my street, which is mostly populated by successful Hispanic and Black skilled blue collar workers and small business owners (I kind of get the vibe that I occupy the role as the neighborhood white dorky guy who can’t fix anything and always has to ask them what part to get from Home Depot). The COVID shutdowns that many even on the left are now saying went over the top made things quite difficult for them, and even though the shutdowns happened under Trump many of them did blame the establishment keyboard warriors for wrecking their livelihood for a year. Right before the shutdowns my son got in a fight with a boy at school and we met the mother to make the peace, during the course of which we found out that she worked at a Wendy’s and took an Uber to work every day because they couldn’t afford a car (being poor is quite expensive, those who understand understand). I don’t know how she survived the shut-downs. Anyway, I don’t mean to re-adjudicate the grand COVID debate here, but suffice it to say there is presumably some daylight between popular, conventional wisdom depictions of minorities and women and what is important to them, in degree if not in kind.

From a Latter-day Saint perspective we see this in our wards in a microcosm; for example, the Mexican immigrant that posts Trump memes (actual experience from my Texas ward), when the most liberal person in your ward is the old white man (another experience), or the first generation Liberian Americans for whom the priesthood ban is not nearly as salient as it is for a multi-generational African American (another anecdotal sense I’ve gotten, which may be inaccurate). Finally, in what is perhaps a paltry but potentially meaningful recompense for our liberal brothers and sisters, in an environment where partisanship is dialed up to an 11 famously conservative Utah was one of only two states where Trump underperformed relative to past elections. Because people, identities, and worldviews are complicated, and they bely the simplistic demographic narratives that we shoehorn them into.

Comments

12 responses to “The Black Menaces, The Election, and Demographic Morality Plays”

On one hand, I want to read your posts because you have interesting ideas which you examine using statistics. On the other hand, I do not like to read your posts because of the general meanness of your approach. Sincere request: Would it be possible for you to write the posts using the interesting ideas and statistics, but without the snide comments?

Please identify which comments in particular.

@PWS: Thanks for your kind words about my ideas and numbers. The commentary is half of the fun. I try not to be too dismissive of other views, and I try to treat any good faith pushback politely. (And I’m also wondering which comment in particular was considered overly snide).

I think one of the big problems is that each side feeds off each other lies and end up creating fake demographics. The left has tried to portray the right as old white mysonogistic Nazis who are trying to destroy America with anti-science and patriarchy while the right tries to portray the left basically as secular humanists who are against God and will censor and cancel anyone who doesn’t agree with them.

The truth is that these portrayals are wrong by both sides. But, because the powers to be keep these insistings each side fears the other and hate mongering continues.

And, quite sadly, as long as we saints continue to pick sides and continue to fear and prod the other we are not of Christ’s true fold and thus none of his. We are not united into one with each other and to God and thus remain in a state without salvation pending. Now my gripes with each side-

My one and only gripe I have with the left (I’m a long time conservative) is that I believe they are behind this whole cancel culture and censorship agenda and that has bled into every facet of society. Everything from censoring the creationism and Intelligent design movements to every form of limiting freedom of speech and worship. I have been censored from almost every blog, forum, discussion from someone or group who leans left over the years whereas I haven’t even once been censored by someone who leans right. That’s a fact.

The problem with the right is that in many instances I believe they prioritize big business over small business and thus supports corruption and monopolies which in turn lobby laws that snuff the small guy. The right are losing core conservative values all the time.

I also enjoyed this thoughtful essay-lite. I think Stephen C used an effective mix of actual facts and his personal experiences to effectively illustrate his chosen point. I fail to see the ‘general meanness’ or ‘snide comments’ that is apparently visible to another T&S participant.

Thx for the post.

I asked ChatGPT to weigh in on some of the issues that Stephen C is discussing in this post. Here is the prompt:

Please evaluate the claim that white Americans hold conservative opinions on social issues, whereas racial and ethnic minorities who have experienced discrimination tend to take the opposite perspective. Please evaluate the narrative that says white Americans are naive because they not see themselves as racist and discriminatory, while people of color are wiser and more empathetic because of the discrimination they have faced during their lives. Evaluate how useful it is for politicians in the Republican and Democratic parties to make these claims, both in terms of rhetoric to motivate certain voter segments and in terms of policies that increase the votes for their own party and decrease the votes for the opposing party. Please include ways that Republicans have been accused of suppressing votes from people of color and evaluate this claim of voter suppression in terms of the need that Republicans will have for votes by people of color given that non-white Americans will become the majority of the electorate by 2045.

Here is the response:

The claim that white Americans tend to hold more conservative views on social issues while racial and ethnic minorities generally lean in the opposite direction is supported by research in political science and sociology. White Americans, particularly older and more religious demographics, have historically shown more conservative positions on issues such as immigration, policing, and LGBTQ+ rights, while Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans often hold more progressive views, likely influenced by their experiences with discrimination and historical marginalization. However, this generalization is nuanced; the views of both white Americans and people of color vary widely based on factors like education, age, religion, and socioeconomic status.

### Naivete vs. Wisdom: A Constructed Narrative?

The narrative that white Americans are “naive” about racism, while people of color possess “wisdom” from their lived experiences, is both partially grounded in social reality and highly politicized. White Americans who are less directly affected by discrimination may have less awareness of its pervasiveness, leading to perceptions that they may overlook systemic inequalities. On the other hand, people of color who experience discrimination may have heightened sensitivity to structural racism. However, this simplified contrast can overlook internal diversity and the complexity within these groups. This narrative, especially when polarized as it sometimes is, risks reducing complex social perspectives into stereotypes that can alienate individuals within these broad categories who don’t fit the mold.

### Political Use of These Claims

Politicians have capitalized on these contrasting perceptions to mobilize voters:

1. **Rhetoric for Voter Mobilization**:

– **Democrats** often emphasize systemic issues like racial inequality and discrimination, aiming to galvanize minority voters and progressive white voters. They may frame their policies as a remedy for historical injustices, portraying the party as one committed to fairness and inclusivity. This rhetoric is intended to inspire loyalty among voters who feel marginalized by societal structures.

– **Republicans** have tended to focus on traditional values and economic freedom, portraying these as universally beneficial and appealing to individual responsibility. However, when Republicans emphasize “law and order” or “border security,” some voters of color see these positions as indirect criticisms of communities of color, sometimes alienating these voters.

2. **Policy Influence**:

– **Democratic policies**: Democrats propose policies aimed at reducing racial inequities, such as criminal justice reform, voting rights protections, and healthcare access. These policies often resonate with voters of color but also appeal to socially conscious white voters.

– **Republican policies**: Republicans emphasize deregulation, tax cuts, and individual responsibility, which appeal to their conservative base, including socially conservative white voters. However, the GOP has started to emphasize policies that could attract voters of color, like promoting school choice and entrepreneurship.

### Republican Accusations of Voter Suppression

Republicans have faced allegations of voter suppression, particularly among communities of color, due to actions such as:

– **Voter ID laws**: Critics argue that these laws disproportionately affect minority and low-income voters who are less likely to possess government-issued identification.

– **Purging voter rolls**: In the name of preventing fraud, some states have purged voter rolls, a practice that can disenfranchise eligible voters who may not realize they need to re-register, often impacting communities of color more significantly.

– **Limited polling stations**: In minority neighborhoods, polling stations are sometimes reduced, which can result in long waits that disproportionately affect working-class voters who have less flexibility in their schedules.

While Republicans argue that these measures are necessary to protect election integrity, studies suggest that such policies can indeed reduce voter turnout among minorities. As the U.S. electorate trends toward a majority non-white demographic, Republicans will likely face challenges if they rely solely on white voters. To remain viable, the party may need to increase its appeal among voters of color. This could mean reshaping its rhetoric and policy platform to address issues relevant to these communities in a way that resonates with their values and concerns.

### Long-Term Implications

By 2045, the electorate will be majority non-white, and both parties will need strategies to capture diverse votes. **Democrats** are likely to continue focusing on issues of racial equity, healthcare, and social justice, while Republicans may need to either moderate or reframe their positions on issues like immigration and criminal justice to avoid alienating non-white voters. For the GOP, continuing tactics perceived as suppressive may backfire as demographic shifts make non-white voter engagement crucial. Republicans who can balance conservative principles with inclusivity could potentially draw support from communities of color, especially on issues like economic empowerment and education.

In sum, both parties use these narratives to galvanize their bases, but shifting demographics may demand that both evolve their rhetoric and policies to create more genuine, broad-based appeal.

Fun read.

Yeah–I think we sometimes forget that there are a lot of Hispanic business owners. And as with any other demographic most of the businesses they own are small–restaurants, auto repair, or what-have-you. And so, naturally, their gonna have real concerns about the economy. And so what we’ve seen this time around — with respect to the Latino vote — is an effect of putting “first things first.” Let’s make sure that we can put food on the table first–and then we can talk about our “loftier” sociopolitical concerns.

They’re–not their.

Yes, this election has finally gotten it through to some people that racial groups do not have homogenous political interests (in particular, 2nd and 3rd generation Latinos are not automatically supportive of more immigration). And despite the heavily gendered campaigns, the gender gap was somewhat smaller than in the past. This is good–we don’t want an election to be a census. I think Jack’s got it right that economics and especially inflation was the chief issue driving voting decisions.

Which makes it ironic that most of the campaign rhetoric around economics was hogwash on both sides. (My training is in economics and campaigns usually have me rolling my eyes, but this was more egregious than usual.) Neither candidate can actually lower prices to what they were in 2020, nor would we want them to. Deflation is really bad for an economy–just ask Japan about their “lost decade” (the 90s) prior to which they were slated to be Asia’s economic great power. Success in dealing with inflation consists of getting prices stable again (check–and without causing a recession!) and making sure incomes rise to match (check, on average). But when prices go up, that’s inflation, and when my salary goes up, that’s my hard work, so it’s no wonder people hate inflation. Especially when they’ve never seen it before (we had a historically long run of low inflation prior to 2021).

Many countries had a post-pandemic inflation episode similar to the US, including all the big EU countries and Japan, suggesting it was driven by things they had in common (the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), not things that were unique to the US (Joe Biden). But that’s the joy of American politics: the thing presidents are primarily judged on, the short-term status of the economy, is something they don’t have a lot of control over. At least not in the positive sense–presidents can certainly disrupt the economy if they so choose.

This is a good post

Supporting RLD’s point, Catherine Rampall at the Washington Post suggests that Trump should just wave his hands the day after the inauguration, announce that he had fixed the economy, then go play golf for four years while Fox News praises his economic miracle. I’ve heard worse ideas.

I don’t mean to imply that all is well with the economy. Too many families are struggling to make ends meet–worse off than their parents were at their age. The median age of first-time home buyers is now *38* (speaking of reasons fewer people have large families). The American Dream seems out of reach for too many people. But the problem is is not inflation and it’s not new: it’s the result of trends that started in the 70s and 80s.

It’s quite a shift that both parties now see the struggles of the middle and working classes as a problem government should solve, but their proposals for solving it range from fanciful to tinkering around the edges. To be fair, there’s no consensus even among experts about what should be done. It will indeed be interesting to see if the right-wing media can convince people that all is well once Trump is in charge, or if he’ll be blamed for how things are like he was in 2020.