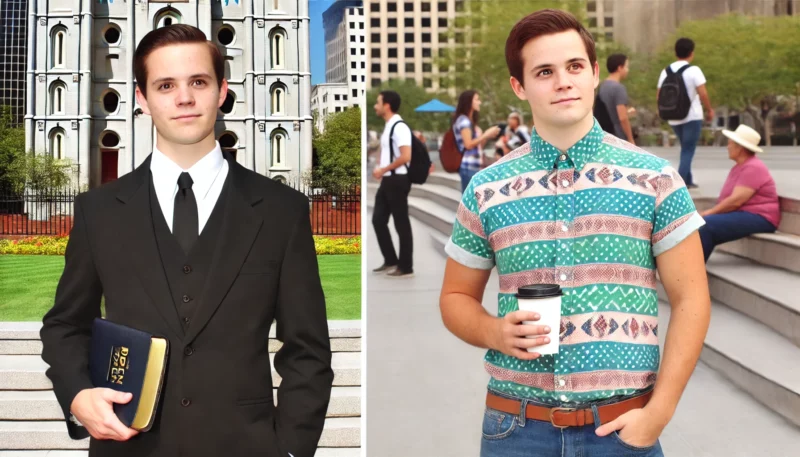

Chat-GPT’s rendition of a very strict, orthodox Mormon, right next to a liberal, heterodox Mormon, because even heterodox Mormons still wear buttoned-up, tucked-in shirts evidently.

O’Sullivan’s law, one of those cute Internet “laws,” states that “any organization or enterprise that is not expressly right wing will become left wing over time.” Like most Internet laws, it kind of holds up, even though exceptions can be found.

There’s something to it in regards to Church-related institutions if you replace left-wing and right-wing with edgy and/or heterodox. For example, one of the early, founding members of Dialogue was Dallin H. Oaks, whereas a simple perusal of the Table of Contents of issues through the years shows a clear veer towards critical studies issues in the Dialogue journal and, presumably, community. I’m not, in this post, making an argument for whether that is a good or bad thing, but the directionality of the drift is clear.

And then of course the classic case is the Maxwell Institute. Not that it was ever “edgy,” just that it clearly shifted from being what could be described as being on the Molly Mormon side of the continuum with its apologetics focus to speaking to a smaller, more academic niche. Again, I have no desire to rehash the old fights over the “coup,” although for the most part I will admit that I think, after the dust has settled, I like the division of labor, and think there’s a healthy amount of variety and distinctiveness among allied groups like Scripture Central, the Religious Studies Center, the Interpreter Foundation, the BH Roberts Foundation, and the Maxwell Institute, each with their own niche and specialties. Still, it is indisputable that that the “coup” was a clear co-opting of the MI to turn it into something else that it had not been before (again, whether that was a good or bad thing is another question). I don’t claim any insider knowledge, but I suspect there were a lot of donors that were confused about what was going on.

My vibes, for what this is worth, is that Sunstone and, possibly, FMH, kind of fit into this category. I might be wrong, but I suspect that in its early days there was a space for a sort of nuanced temple recommend-holding, active believer (e.g. Peggy Fletcher-Stack in her early Sunstone days) or maybe even the occasional social conservative in those organizations, but you’d be hard pressed to find anybody in that category in there now in any meaningful numbers (fun story, I was invited to give a presentation at Sunstone, so my sweet, sweet, born-and-raised Latter-day Saint grandmother wanted to come and see her grandson talk, and there was a bit of a culture shock at Sunstone Salt Lake as she sat in the middle of a very, very, anti/ex-Mormon crowd).

As I’ve noted before, the orthodox are either the fuel or the foil for many of the more heterodox organizations (on the left and the right, now that we have right-heterodox orgs such as the polygamy deniers and Snufferites). The heterodox organizations get a certain energy from responding to or critiquing the orthodox, and in the case of the left-heterodox their membership largely stems from the formerly orthodox, but like faiths’ relationship with the outside world there has to be an optimal tension with the parent organization. At some point you’ve left so much that you’ve picked up other things to spend your time with, but the sweet spot seems to be the somewhat believing person wrestling with hard questions and making it work, but oftentimes the institutions that are geared towards such a demographic drift, iceberg like, into the more explicitly post-Mormon or cultural-Mormon territory, at which point new organizations arise to fill in that gap.

Comments

14 responses to “O’Sullivan’s Law and Latter-day Saint-Adjacent Organizations”

I had never heard that called “O’Sullivan’s Law” before. I’ve always seen it as Conquest’s Second Law (Robert Conquest – the historian/poet [and former capital-C communist] who became a research fellow at Standford University’s Hoover Institution)

For completeness sake, “Conquest’s Three Laws” are:

1. Everyone is conservative about what he/she knows best.

2. Any organization not explicitly right-wing will eventually become left-wing.

3. The behavior of any bureaucratic organization is best understood by

assuming that a secret cabal of its enemies controls it.)

However, some googling shows that it was O’Sullivan’s First Law and internet-memory caused them to get mixed up. (Wikipedia says “The second law [attributed to Conquest] is O’Sullivan’s first law, which was stated by John O’Sullivan in his article “O’Sullivan’s First Law”)

So, I just learned something new.

I haven’t heard of # 1, but I have relied very heavily on # 3 in my career to give me grace.

Many faithful members (including myself) are bothered by criticism of the Church and will withdraw from a community where there’s a lot of it. Meanwhile, I don’t get the sense that critics of the Church are bothered in the same way by statements of faith. So if you start with a mixed community of faithful members and critics, it’s the faithful members who will most likely withdraw and leave the room to the critics, not the other way around. I’m not nearly as “online” as you are, Stephen, but I suspect that fits some of the communities you mention. I don’t think it has much relevance to the Maxwell Institute though.

(No, “faithful members” and “critics” doesn’t map to “orthodox” and “heterodox.” I don’t find those categories useful at all.)

I find the “faithful” distinction to be too polemical to really useful in general discussion. At this point it’s considered in poor taste to label virtually any group or person as not being “faithful” unless they’re at, like John Dehlin-level, so yes, while orthodox/heterodox doesn’t neatly map onto faithful or not, it’s a term that is more neutral and both the “orthodox” and “heterodox” can agree with the categorization.

That’s fair on “faithful” being polemical–I could (and probably should) have stuck with “people who are bothered by criticism” and “people who criticize.”

I’m curious if you really find people agree with being called “heterodox.” Some people might call me heterodox, but I’d object. It feels like a power move to say “What I think is orthodox and those who disagree with me are heterodox.” (And it is always those who consider themselves orthodox who make the distinction and draw the boundaries, isn’t it?)

I’m pretty dubious about any attempt to divide Church members into categories, whether it’s Orthodox vs. Heterodox, Iron Rodders vs. Liahonas or whatever. It seems like if you scratch under the surface there’s usually a clear hierarchy, with the people doing the dividing putting themselves in what they see as the superior group.

I agree that we shouldn’t take categorizations too seriously, but those empirical clusters of attitudes do in fact exist, don’t they? And if so, I think it should be okay to talk about it. Just because there are exceptions doesn’t mean we don’t talk about average empirical trends or patterns.

Supposing we had a big data set of member attitudes on various topics, could we identify clusters? Almost certainly. Would there be exactly two of them? I’d be surprised. Could we usefully label one cluster as “orthodox”? Not without defining orthodoxy first, and unless we simply go with a rule like “the biggest cluster is the orthodox one” that will involve value judgements.

Is Dan Peterson’s “Nephi and His Asherah” article (pre-“coup” Maxwell Institute) more orthodox than the “Brief Theological Introductions to the Book of Mormon” series (post-“coup”)? How about “All Things New” by the Givens? (These are rhetorical questions meant to illustrate the difficulties involved–no need to answer.)

One thing I love about our theology is that we know we don’t know everything. So if orthodoxy is “conforming to established doctrine especially in religion” two people can conform to all our established doctrine and still disagree about a great many things. Of course, in practice we also disagree on what’s established. So given these hypothetical clusters, one could look at each one and identify which are orthodox and which are not, but I’m pretty confident 1) people would disagree about the classification, and 2) almost everyone who is an active member of the Church will label the cluster they’re in “orthodox.”

Yippee, more boundary maintenance and navel gazing about it, from the “radical orthodoxy” crowd. Yawn.

@ RLD: A recent analysis did just that (https://www.deseret.com/faith/2024/2/9/24067608/latter-day-saint-survey-shows-cross-generational-faith/); its authors are clearly apologetic sellouts though ;)

I think we can probably agree to disagree on the usefulness of the term “orthodox.” I think most people would intuit that it’s essentially whether your views adhere to those of the Church’s teachings. That obviously begs the question and yes, the circle of canonical scripture is pretty small, (and I would argue that even that is somethin of a myth), and instead we have overlapping concentric circles of authoritativeness, but there is some reality there, it isn’t all arbitrary even if the exact boundaries are hard to define.

And I’ll push back a little bit on “anyone active would consider themselves orthodox.” I’m thinking of many of the active-but-somewhat-iconoclastic-or-edgy types wouldn’t see much of a problem with seeing themselves as heterodox (e.g. I suspect Stephen Fleming in the post above would be fine labelling his BoM views as heterodox). As I am sure that they would be quick to point out, there have been a handful of times (almost exclusively with race issues) when heterodox turned out to be correct, (e.g. the interracial marriage in early Utah would have been very heterodox), so it’s not strictly a pejorative term, but I do find it useful because there are some that try to pass themselves off as orthodox because that gives them a certain influence and cachet over the rank-and-file normies when they’re really not, so I think clarity on these points is important, as there are often bad faith motivations for being obscurantist about what you actually believe. (One reason why, even though I obviously disagree, I appreciate Fleming’s candor and openness).

This says it all: “but I do find it useful because there are some that try to pass themselves off as orthodox because that gives them a certain influence and cachet over the rank-and-file normies when they’re really not, so I think clarity on these points is important, as there are often bad faith motivations for being obscurantist about what you actually believe.”

So apparently, “clarity” on this idea is “important” so that…. what? So that fellow congregants can be adequately boxed and categorized? Or one can know when to dismiss someone else’s “cachet” or “influence”? Or so that one can determine who is REALLY a true scotsman or not? Good grief. Have at it, i guess.

But wow, what a weird worldview.

Was Nibley “orthodox” or “heterodox”? Was Hugh Brown “orthodox” or “heterodox”? Should wage earners pay tithing on gross or net? Do you crinkle your water bottle like Pres. Nelson or not?

What utter silliness. We’re all just travelers.

I think this quote from Neal A Maxwell answers adds light to Stephen’s comment:

While living amid the foreseen “distress of nations, with perplexity,” members also have prophetic leadership which provides direction. (Luke 21:25; see also D&C 88:79.) Several times a year, we sustain fifteen Apostles as prophets, seers, and revelators. So we know to whom to look, even though there are a few members who “seek not the welfare of Zion” and “set themselves up for a light.” (2 Ne. 26:29.)

@T&S is 16 people…: Here, which is the context of the post, I’m referring to LDS influencers and thought leaders, not what Brother Bill Jones in Elder’s Quorum thinks of apostolic succession. But yes, if you are going to try to be an influencer than full disclosure about where you’re coming from is warranted.

Genuinely curious since I don’t do a lot of cluster analysis: how did you settle on two clusters in that data? Seems like three would improve the fit, mostly by sweeping in those points in the lower left that are long way from cluster one. Or, since the data really looks like one cluster and points at various distances from it, maybe an alternative classifier that didn’t insist cluster two must be a sphere?

More fundamentally, your questions are pretty much all about “established doctrine.” That’s not a criticism since your goal was to measure orthodoxy, but it does make most active members look the same. If you’d asked about things like evolution, historical accuracy of the Old Testament, racism in the Book of Mormon, Nephi and Captain Moroni as role models, origin of the priesthood ban, eternal polygamy, the meaning of “eternal increase”, mothers working outside the home, proper attire for church, or what it means to be saved by grace, you’d get a lot more variety. You’d also get into areas where members would object to being labeled as heterodox just because they don’t believe Elisha summoned bears to kill children (and watch yourself around President Oaks).

The number of optimal clusters is automatically determined by the K-means cluster algorithm (specifically the “elbow method”) Basically, it determines the number of clusters that maximize the information about the group before the information gained per cluster drops down.

Sure, it’s fuzzy what is “heterodox” or “orthodox,” as it is fuzzy what is “established doctrine.” I still think that heterodox/orthodox is a relatively being way to label that continuum, but I’d be open to other terminology if it could tap into the some concept.