A guest post from Josh Coates and Stephen Cranney

This is one of a series of posts discussing results from a recent survey of current and former Latter-day Saints conducted by the BH Roberts Foundation. The technical details are in the full methodology report here.

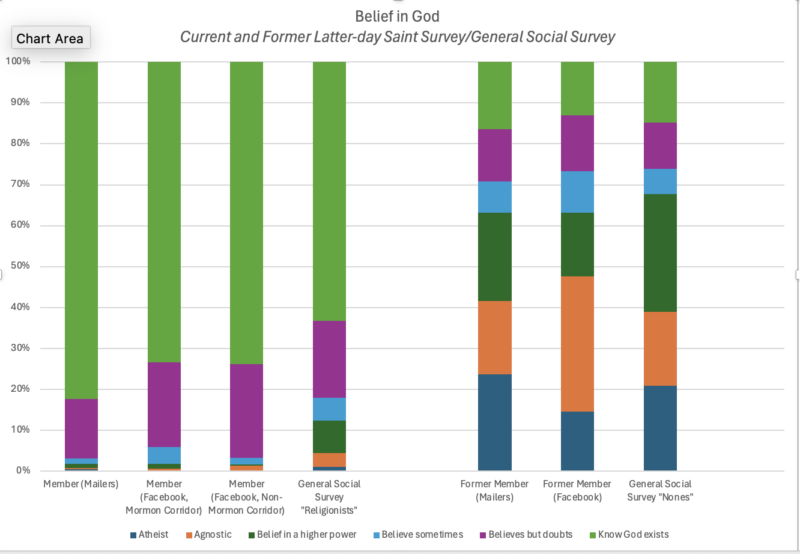

In the 2023 CFLDSS we asked the standard question about belief in God that is also asked in the General Social Survey, an omnibus survey of Americans asked just about every year that has asked a question about belief in God since the late 1980s.

“Which statement comes closest to expressing what you believe about God.”

- I don’t believe in God

- I don’t know whether there is a God and I don’t believe there is any way to find out

- I don’t believe in a personal God, but I do believe in a Higher Power of some kind

- I find myself believing in God some of the time, but not at others

- While I have doubts, I feel that I do believe in God

- I know God really exists and I have no doubts about it

The graph below has the result for our three current member samples, the two former member samples, the 2022 General Social Survey sample of respondents who are “Nones,” and indicated no religious affiliation, and the 2022 General Social Surveys sample of respondents who indicated a religious faith. (And yes, we know that there are agnostics that don’t fit into option 2, but for the sake of simplicity here they are labeled “agnostics.”)

One occasionally hears the idea that maybe Mormonism can become enough of an ethno-religious heritage that you could, in theory, be a convinced non-believer who still identifies with the label (call it the “Sterling McMurrin model”). This is a thing with Jews, so there is some precedent (when Golda Meir was asked if she believed in God she quipped, in a very Golda Meir way, “I believe in the Jewish people, and the Jewish people believe in God.”)

One occasionally hears the idea that maybe Mormonism can become enough of an ethno-religious heritage that you could, in theory, be a convinced non-believer who still identifies with the label (call it the “Sterling McMurrin model”). This is a thing with Jews, so there is some precedent (when Golda Meir was asked if she believed in God she quipped, in a very Golda Meir way, “I believe in the Jewish people, and the Jewish people believe in God.”)

However, we’ve always been skeptical about the feasibility of this option for Latter-day Saints. For one, we just don’t have the thousands of years of shared ethno-religious experience that Jews do. For two, membership and activity is much more reified. We are a high-demand faith, the borders between being in and out are much clearer than they would be if we were a less centralized faith with thousands of different religious authorities. The results here bear out this sentiment. If people lose faith in God, they typically leave the Church. Of course, as with all rare events there are exceptions, but they are, in fact, rare.

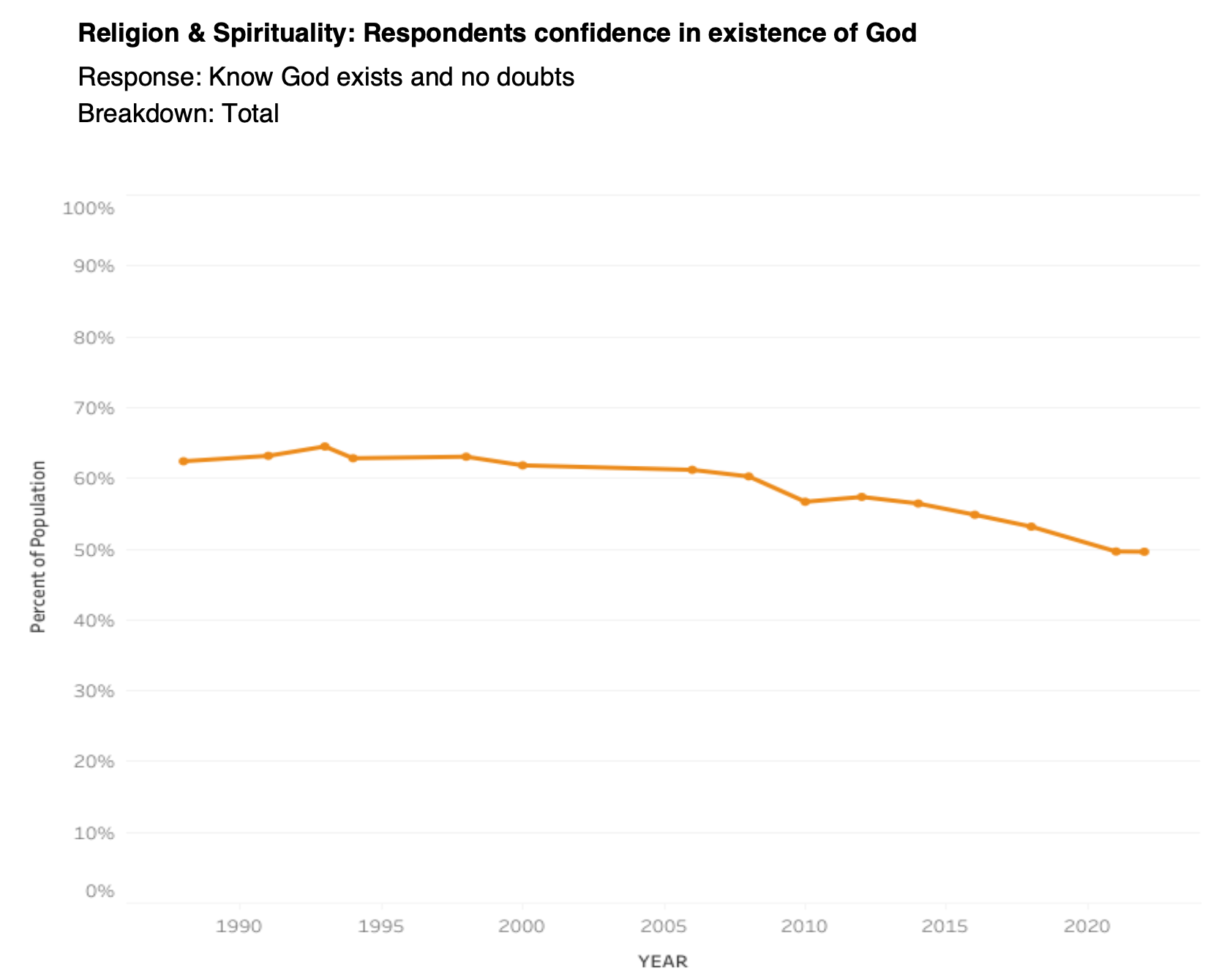

We are still very much a nation of believers in God. Although this number has been changing, believers are still a strong majority, with about half still saying they have no doubts about God’s existence.

Even among religious “Nones” and ex-members the atheist/”agnostic” option isn’t a majority: most still have some kind of belief in something higher. Of course, they are also less likely to state that they know God exists. Rather their belief in God is characterized more by ambiguity than a firm belief one way or another.

Latter-day Saints are more likely than other religionists to state that they know God exists. (Speculatively, we wonder how much of the comfort with this option might stem from the fact that “know” is a common, almost stock verb in our testimonies culturally). The other big difference compared to generic religionists is that Latter-day Saints score negligibly on the higher power option. Again, this isn’t a big surprise theologically, our God has flesh and bones, we’re not a “higher power” kind of faith.

Comments

6 responses to “What do Members and Former Members Believe About God? Insights from the B.H. Roberts Foundation’s Current and Former Latter-day Saint Survey”

It’s worth pointing out that the mail survey was only sent to the “Mormon corridor,” while the Facebook survey “focused on users showing interest in BYU, other Utah-centric educational institutions, their sports teams, and Utah in general.” That’s because they say the Mormon corridor is “the sociocultural heart of the Church.”

I get how difficult it is to survey members and ex-members. We could argue about the merits of their sampling methods vs. Jana Riess’s. But their justification for focusing on Utah has me rolling my eyes.

At any rate, bear in mind that this survey does not and was not intended to describe the Church as a whole.

This does strengthen one of the OP’s points though: if there are essentially no “cultural Mormons” in Utah, we certainly wouldn’t expect to find significant numbers of them anywhere else.

This is interesting, but it doesn’t count those who are still active, or involved with Mormonism who have stopped believing in the current church, but still might believe fully in God. Sort of like me. I reject Joseph Smith as a prophet of God, but oddly, I still believe in much of his “restored” Christianity. For example, I don’t believe in the trinity, but an embodied God. My husband still believes, and I am culturally Mormon. I even attended with this belief system for some 30 years. I am “involved with Mormonism” have home teachers, visiting teachers, (yeah, what we call them has changed, but the change is unnecessary relabeling) follow Mormonism closer than my believing husband. So, I would have shown up in your Facebook survey divisions as a “believing Mormon” but I am not. So, maybe your “cultural Mormons” are confused in your survey with believing Mormons.

You’re right, Anna: the OP deals with a single dimension of belief and is pretty clear about that. I should not have slapped the over-broad label of “cultural Mormon” on it.

Hi Anna. People were counted as members simply if they self-identified as members of the Church. Obviously there are complicated cases like yours, but you have to draw the line somewhere, so for this particular survey that is where the line was. Your case is interesting because it shows some metaphysical beliefs formed in Mormonism can remain even when others are discarded.

The linked PDF really focuses on methodology and I couldn’t find any results on the foundation’s web site, but it looks like the survey asked questions that are likely relevant to Anna’s situation (“Whether Joseph Smith saw God”, “Whether plural marriage was a

mistake”, etc.). Perhaps topics for future posts.