As Latter-day Saints we often refer to “disciple-scholars,” or people who embody the idea that the glory of God is intelligence, and for whom their scholarship is a form of discipleship. While there are a handful of Latter-day Saint cases people invoke (most classically Hugh Nibley, Richard Bushman, or Henry Eyring), I thought I’d step outside the Latter-day Saint tradition to brainstorm a broader list.

I suspect the golden era of disciple-scholarship was the 17th and 18th century, when nearly every revolutionary scientist was deeply motivated by the idea that they were exploring the handiwork of God (Newton, Leibniz, Pascal). We’re past that golden age now, and while Elaine Ecklund at Rice University has written a bunch of books on how many scientists actually are religious, on the whole it is true that they typically aren’t a religious lot any more.

I could be snarky and point out that most of the geniuses who revolutionized our understanding of the universe on napkins in candlelight were religious, while the non-religious scientists of today are mostly involved in measuring out values to more decimal places, but I concede that most of this is due to the fact that by the time physics is developed enough that new discoveries can only be made with multi-billion dollar pieces of hardware, the secularization process has already thoroughly run its course. Nonetheless, I’m a strong believer that religious belief can animate the scientific venture, anchoring it in something beyond a quirky Rubik’s cube-like interest, and giving it an added measure of holiness and gravity, so I started curating a list of example scholars. (Here, “disciple-scholar” is broad, and includes non-religious or non-believers in a personal God whose science was still animated by a sense of awe at a higher power).

However, after I started curating this list, I realized that it was much too large for one post, so I’m breaking it down piece by piece. Below is my list of non-LDS disciple-scholar physicists in the 20th and 21st centuries. All italicized quotes are from Wikipedia unless otherwise stated.

Einstein

Einstein was famously obscure about his spiritual beliefs, and certainly not traditionally religious. I don’t want to open up the can of worms here, my read is that he had a pantheistic belief system that was not quite him simply loan shifting “God” for “science,” but he did approach that God manifested in the orderliness of the universe with what could be described as a deep reverence that motivated his work.

Georges Lemaître

Belgian priest who first hypothesized the Big Bang. Initially there was resistance to the idea because secularists were skeptical that a Catholic priest happened to come up with a theory that seemed to conveniently support Catholic cosmology. However, later in life he stepped away from connecting his cosmological discoveries to religious principles.

Max Planck

Spoke often about God. “Both religion and science require a belief in God. For believers, God is in the beginning, and for physicists He is at the end of all considerations … To the former He is the foundation, to the latter, the crown of the edifice of every generalized world view”

Also, another quote that should appeal to Latter-day Saints given D&C 131 spirit and matter theology.

As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clear headed science, to the study of matter, I can tell you as a result of my research about atoms this much: There is no matter as such. All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent spirit [orig. Geist]. This spirit is the matrix of all matter.

Werner Heisenberg

Yes, he was the head of the Nazi nuclear program. I don’t know the details, but he was friends with Einstein later in life, and Einstein was not quick to forgive Germans or former Nazis, so I suspect it was complicated.

Heisenberg referred to nature as “God’s second book” (the first being the Bible) and believed that “Physics is reflection on the divine ideas of Creation; therefore physics is divine service”. This was because “God created the world in accordance with his ideas of creation” and humans can understand the world because “Man was created as the spiritual image of God”

William Daniel Phillips

Won the Nobel Prize for using lasers to cool an atom to closer to absolute zero than anybody had previously. The one person on this list that I’ve seen in person. I believe (but might be mistaken) that he gave a lecture at BYU that I attended when I was in elementary school or thereabouts. He made one off-hand reference to God designing things, but otherwise focused on laser cooling. After he married became a practicing Christian. Founded the International Society for Science and Religion.

Arthur Compton

Nobel prize winner that discovered the dual wave/particle nature of subatomic particles.

Compton lectured on a “Man’s Place in God’s World” at Yale University, Western Theological Seminary and the University of Michigan in 1934–35. The lectures formed the basis of his book The Freedom of Man. His chapter “Death, or Life Eternal?” argued for Christian immortality and quoted verses from the Bible.From 1948 to 1962, Compton was an elder of the Second Presbyterian Church in St. Louis. In his later years, he co-authored the book Man’s Destiny in Eternity. Compton set Jesus as the center of his faith in God’s eternal plan. He once commented that he could see Jesus’ spirit at work in the world as an aspect of God alive in men and women.

Abdus Salam

First Muslim winner of a science Nobel Prize for his work synthesizing the electromagnetic and weak nuclear force.

Salam was an Ahmadi Muslim, who saw his religion as a fundamental part of his scientific work. He once wrote that “the Holy Quran enjoins us to reflect on the verities of Allah’s created laws of nature; however, that our generation has been privileged to glimpse a part of His design is a bounty and a grace for which I render thanks with a humble heart.” During his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Physics, Salam quoted verses from the Quran and stated:

“Thou seest not, in the creation of the All-merciful any imperfection, Return thy gaze, seest thou any fissure? Then Return thy gaze, again and again. Thy gaze, Comes back to thee dazzled, aweary.” (67:3–4) This, in effect, is the faith of all physicists; the deeper we seek, the more is our wonder excited, the more is the dazzlement for our gaze.

Of course, it is ironic that his co-winner, Steven Weinberg gave us the classic line “With or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil – that takes religion.”

Robert Millikan

Known to Latter-day Saints because he was given the Nobel Prize for work determining the charge of an electron that probably should have been shared with his Latter-day Saint student Harvey Fletcher. (Ironically, it appears that the removal of his name on buildings due to his eugenics beliefs was later vehemently opposed by prominent Latter-day Saint mathematician Thomas Hales).

A religious man and the son of a minister, in his later life, Millikan argued strongly for a complementary relationship between science and Christianity. He dealt with this in his Terry Lectures at Yale in 1926–27, published as Evolution in Science and Religion. He was a Christian theist and proponent of theistic evolution.

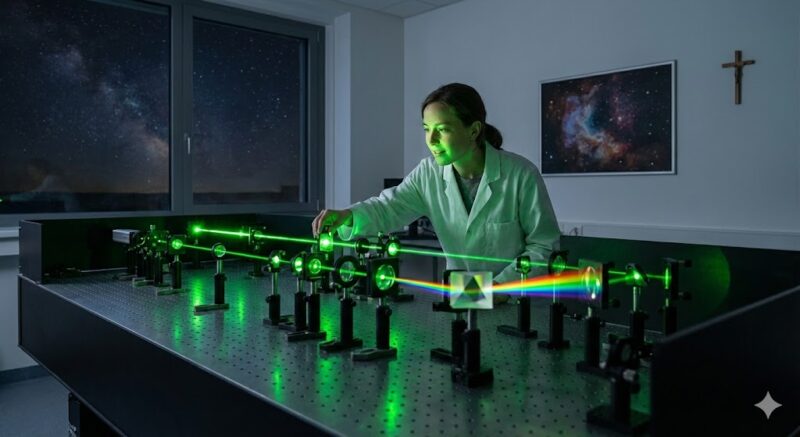

Charles Townes

Laser pioneer.

A religious man and a member of the United Church of Christ, Townes believed that “science and religion [are] quite parallel, much more similar than most people think and that in the long run, they must converge”. He wrote in a statement after winning the Templeton Prize during 2005: “Science tries to understand what our universe is like and how it works, including us humans. Religion is aimed at understanding the purpose and meaning of our universe, including our own lives. If the universe has a purpose or meaning, this must be reflected in its structure and functioning, and hence in science.”

Townes’s opinions concerning science and religion were expounded in his essays “The Convergence of Science and Religion”, “Logic and Uncertainties in Science and Religion”, and his book Making Waves. Townes felt that the beauty of nature is “obviously God-made” and that God created the universe for humans to emerge and flourish. He prayed every day and ultimately felt that religion is more important than science because it addresses the most important long-range question: the meaning and purpose of our lives. Townes’s belief in the convergence of science and religion is based on claimed similarities:

- Faith. Townes argued that the scientist has faith much like a religious person does, allowing him/her to work for years for an uncertain result.

- Revelation. Townes claimed that many important scientific discoveries, like his invention of the maser/laser, occurred as a “flash” much more akin to religious revelation than interpreting data.

- Proof. During this century the mathematician Kurt Gödel discovered that there can be no absolute proof in a scientific sense. Every proof requires a set of assumptions, and there is no way to check whether those assumptions are self-consistent because other assumptions would be required.

- Uncertainty. Townes believed that we should be open-minded to a better understanding of science and religion in the future. This will require us to modify our theories, but not abandon them. For example, at the start of the 20th century physics was largely deterministic. But when scientists began studying the quantum mechanics, they realized that indeterminism and chance play a role in our universe. Both classical physics and quantum mechanics are correct and work well within their own bailiwick, and continue to be taught to students. Similarly, Townes believes that growth of religious understanding will modify, but not make us abandon, our classic religious beliefs.

Arthur Schawlow

Collaborator with Charles Townes in his pioneering laser work.

He participated in science and religion discussions. Regarding God, he stated, “I find a need for God in the universe and in my own life.”

John Polkinghorne

Professor of Mathematical Physics at Cambridge, but resigned his chair to become an Anglican priest. “Author of five books on physics and twenty-six on the relationship between science and religion; his publications include The Quantum World (1989), Quantum Physics and Theology: An Unexpected Kinship (2005), Exploring Reality: The Intertwining of Science and Religion (2007), and Questions of Truth (2009).”

Freeman Dyson

Needs no introduction. One of my favorite, very Latter-day Saint quotes is by him: “No matter how far we go into the future, there will always be new things happening, new information coming in, new worlds to explore, a constantly expanding domain of life, consciousness, and memory.”

Also, a fan of the Book of Mormon. He has referred to Latter-day Saint friends he has; I kind of suspect that there might be a Henry B. Eyring connection through Henry Eyring, but I’m just speculating.

Wolfgang Pauli

Sort of an Einstein-type pantheist. “Pauli thought that elements of quantum physics pointed to a deeper reality that might explain the mind/matter gap and wrote, ‘we must postulate a cosmic order of nature beyond our control to which both the outward material objects and the inward images are subject.’”

Jennifer Wiseman

Chief Scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope

She has been featured in the John Templeton Foundation funded project, The Purposeful Universe

Wiseman is a Christian and a Fellow of the American Scientific Affiliation and a member of the BioLogos Board of Directors. On June 16, 2010, Wiseman was introduced as the new director for the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) program, Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion. She remained in that position until August 2022 when she was succeeded by Katharine Hinman. Her work for AAAS included speaking to organizations about her beliefs on Christianity and Science.

Alister McGrath

Former atheist. Aside from being a faculty member at Oxford, McGrath has also taught at Cambridge University and is a teaching fellow at Regent College. McGrath holds three doctorates from the University of Oxford: a doctoral degree in molecular biophysics, a Doctor of Divinity degree in theology, and a Doctor of Letters degree in intellectual history. McGrath is noted for his work in historical theology, systematic theology, and the relationship between science and religion, as well as his writings on apologetics.He is also known for his opposition to New Atheism and antireligion and his advocacy of theological critical realism.Among his best-known books are The Twilight of Atheism, The Dawkins Delusion? Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life, and A Scientific Theology.

Ard Louis

Born in the Netherlands, and raised in Gabon. Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford, where he leads an interdisciplinary research group that investigates scientific problems on the border between disciplines such as chemistry, physics, and biology,and is also director of graduate studies in theoretical physics.

With David Malonehe made the 4-part documentary Why Are We Here for Tern TV.

Louis also appears in the episode Proof of God in the series The Story of God with Morgan Freeman…Louis identifies as a Christian.

Victor Francis Hess

Austrian–American experimental physicist who shared the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physics with Carl David Anderson for his discovery of cosmic rays.

Hess was a practicing Roman Catholic. In 1946, he wrote on the topic of the relationship between science and religion in his article “My Faith”, in which he explained why he believed in God.

Guglielmo Marconi

One of the inventors of the radio.

In 1931, Marconi personally introduced the first radio broadcast of a Pope, Pius XI, and announced at the microphone: “With the help of God, who places so many mysterious forces of nature at man’s disposal, I have been able to prepare this instrument which will give to the faithful of the entire world the joy of listening to the voice of the Holy Father.”

Igor Sikorsky

Aerospace engineer pioneer that invented a lot of different kinds of aircraft.

Sikorsky was a deeply religious Russian Orthodox Christian, and authored two religious and philosophical books (The Message of the Lord’s Prayer and The Invisible Encounter). Summarizing his beliefs, in the latter he wrote:

Our concerns sink into insignificance when compared with the eternal value of human personality — a potential child of God which is destined to triumph over life, pain, and death. No one can take this sublime meaning of life away from us, and this is the one thing that matters.

Arthur Eddington

English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician….The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the luminosity of stars, or the radiation generated by accretion onto a compact object, is named in his honour.

Around 1920, he foreshadowed the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars, in his paper “The Internal Constitution of the Stars”. At that time, the source of stellar energy was a complete mystery; Eddington was the first to correctly speculate that the source was fusion of hydrogen into helium….He also conducted an expedition to observe the solar eclipse of 29 May 1919 on the Island of Príncipe that provided one of the earliest confirmations of general relativity, and he became known for his popular expositions and interpretations of the theory.

Eddington believed that physics cannot explain consciousness – “light waves are propagated from the table to the eye; chemical changes occur in the retina; propagation of some kind occurs in the optic nerves; atomic changes follow in the brain. Just where the final leap into consciousness occurs is not clear. We do not know the last stage of the message in the physical world before it became a sensation in consciousness”.

Ian Barbour, in his book Issues in Science and Religion (1966), p. 133, cites Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World(1928) for a text that argues the Heisenberg uncertainty principle provides a scientific basis for “the defense of the idea of human freedom” and his Science and the Unseen World (1929) for support of philosophical idealism, “the thesis that reality is basically mental”.

James Jeans

English physicist, mathematician and an astronomer. He served as a secretary of the Royal Society from 1919 to 1929, and was the president of the Royal Astronomical Society from 1925 to 1927, and won its Gold Medal…

Jeans espoused a philosophy of science rooted in the metaphysical doctrine of idealism and opposed to materialism in his speaking engagements and books. His popular science publications first advanced these ideas in 1929’s The Universe Around Us when he likened “discussing the creation of the universe in terms of time and space,” to, “trying to discover the artist and the action of painting, by going to the edge of the canvas.” But he turned to this idea as the primary subject of his best-selling1930 book, The Mysterious Universe, where he asserted that a picture of the universe as a “non-mechanical reality” was emerging from the science of the day.

The Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter… we ought rather hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter.

—James Jeans, The Mysterious Universe,

In a 1931 interview published in The Observer, Jeans was asked if he believed that life was an accident or if it was, “part of some great scheme.” He said that he favored, “the idealistic theory that consciousness is fundamental, and that the material universe is derivative from consciousness,” going on to suggest that, “each individual consciousness ought to be compared to a brain-cell in a universal mind.”

In his 1934 address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Aberdeen as the Association’s president, Jeans spoke specifically to the work of Descartes and its relevance to the modern philosophy of science. He argued that, “There is no longer room for the kind of dualism which has haunted philosophy since the days of Descartes.”

When Daniel Helsing reviewed The Mysterious Universe for Physics Today in 2020, he summarized the philosophical conclusions of the book, “Jeans argues that we must give up science’s long-cherished materialistic and mechanical worldview, which posits that nature operates like a machine and consists solely of material particles interacting with each other.” His evaluation of Jeans contrasted these philosophical views with modern science communicators such as Neil deGrasse Tyson and Sean Carroll who he suggested, “would likely take issue with Jeans’s idealism.”

Leave a Reply