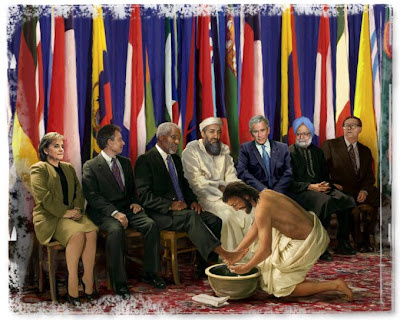

A controversial image, but I think it makes the radical love point quite well.

The infamous Nickel Mines massacre of Amish schoolchildren–and the community’s supernal forgiveness towards the killer and his family–is familiar to Latter-day Saints through President Faust’s 2007 address “The Healing Power of Forgiveness.” For those of you who do not remember the talk, President Faust’s discussion is worth citing at length, but feel free to skip ahead if you have already read it.

In the beautiful hills of Pennsylvania, a devout group of Christian people live a simple life without automobiles, electricity, or modern machinery. They work hard and live quiet, peaceful lives separate from the world. Most of their food comes from their own farms. The women sew and knit and weave their clothing, which is modest and plain. They are known as the Amish people.

A 32-year-old milk truck driver lived with his family in their Nickel Mines community. He was not Amish, but his pickup route took him to many Amish dairy farms, where he became known as the quiet milkman. Last October he suddenly lost all reason and control. In his tormented mind he blamed God for the death of his first child and some unsubstantiated memories. He stormed into the Amish school without any provocation, released the boys and adults, and tied up the 10 girls. He shot the girls, killing five and wounding five. Then he took his own life.

This shocking violence caused great anguish among the Amish but no anger. There was hurt but no hate. Their forgiveness was immediate. Collectively they began to reach out to the milkman’s suffering family. As the milkman’s family gathered in his home the day after the shootings, an Amish neighbor came over, wrapped his arms around the father of the dead gunman, and said, “We will forgive you.”Amish leaders visited the milkman’s wife and children to extend their sympathy, their forgiveness, their help, and their love. About half of the mourners at the milkman’s funeral were Amish. In turn, the Amish invited the milkman’s family to attend the funeral services of the girls who had been killed. A remarkable peace settled on the Amish as their faith sustained them during this crisis.

One local resident very eloquently summed up the aftermath of this tragedy when he said, “We were all speaking the same language, and not just English, but a language of caring, a language of community, [and] a language of service. And, yes, a language of forgiveness.” It was an amazing outpouring of their complete faith in the Lord’s teachings in the Sermon on the Mount: “Do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you.”

The family of the milkman who killed the five girls released the following statement to the public:

“To our Amish friends, neighbors, and local community:

“Our family wants each of you to know that we are overwhelmed by the forgiveness, grace, and mercy that you’ve extended to us. Your love for our family has helped to provide the healing we so desperately need. The prayers, flowers, cards, and gifts you’ve given have touched our hearts in a way no words can describe. Your compassion has reached beyond our family, beyond our community, and is changing our world, and for this we sincerely thank you.

“Please know that our hearts have been broken by all that has happened. We are filled with sorrow for all of our Amish neighbors whom we have loved and continue to love. We know that there are many hard days ahead for all the families who lost loved ones, and so we will continue to put our hope and trust in the God of all comfort, as we all seek to rebuild our lives.”

How could the whole Amish group manifest such an expression of forgiveness? It was because of their faith in God and trust in His word, which is part of their inner beings. They see themselves as disciples of Christ and want to follow His example.

Hearing of this tragedy, many people sent money to the Amish to pay for the health care of the five surviving girls and for the burial expenses of the five who were killed. As a further demonstration of their discipleship, the Amish decided to share some of the money with the widow of the milkman and her three children because they too were victims of this terrible tragedy.

I recently read a book on the event (Amish Grace, there was also a movie that evidently did quite well, but for the life of me I can’t figure out where it’s streaming). The President Faust summary is tear-jerking enough, but it actually omits a lot of other tear-wringing details: one of the girls offered to be shot first to give the others a chance to escape, another one heard a voice from heaven telling her to run, and the family of the milkman were contacted by Amish neighbors hours after the shooting.

The book was analytical as well as moving. In it, they discuss the Amish theology and culture of forgiveness, give other examples to show that it was not a one-off, and address common rejoinders to the Amish’s response. In terms of their history and theology, the Amish are raised from the time they are children with stories of martyrs who died rather than raise a hand in anger against their assailants during the Anabaptist persecutions. For example, Dirk Willems was a very famous early believer who escaped jail across a frozen pond with a guard in hot pursuit. When the pursuer fell through the ice, Willems had a seeming God-given opportunity to escape, but turned back and rescued his guard, which then re-arrested him and burned him at the stake while he was praising God.

Of course, we Latter-day Saints did not take that route, and I’m not saying that we should. But I do think it is possible to exhibit the kind of radical forgiveness of the Amish without subscribing to extreme pacifism like they do. (As a sidebar, it’s amusing to me when people accuse us of attempting to assassinate Governor Boggs. Not the idea that we may have been involved in the assassination attempt, who knows, but rather the idea that trying to assassinate a man who ordered us exterminated is a problem).

But back to the Amish. Given this strong sense of pacifism and extreme forgiveness, their response to the Nickel Mine shooting, while aberrant to our highly cynical world, was not unexpected for those who knew the community. Indeed, they had exercised acts of extreme, decisional forgiveness (a technical term I was unaware of before reading this book) many times in the past. Just a few examples from the book.

- A reckless driver killed a honeymooning bride when he tried to pass them and the horse turned into his car. The driver’s parents took him to their house to make the peace, they forgave him and invited him to dinner. He avoided jail time because of the flood of requests from the Amish community that the judge received to grant him leniency. He still meets with them about once a year. They came to his wedding, and supported him financially when his wife and he spent time at missionaries overseas.

- An Amish mother’s son was hit and (eventually) killed by a driver. “As the investigating officer placed the driver of the car in the police cruiser to take him for an alcohol test, the mother of the injured child approached the squad car to speak with the officer. With her young daughter tugging at her dress, the mother said, ‘Please take care of the boy.’ Assuming she meant her critically injured son, the officer replied, ‘The ambulance people and doctor will do the best they can. The rest is up to God. The mother pointed to the suspect in the back of the police car. “I mean the drive. We forgive him.”

- Sometimes it’s not so accidental. A pair of home burglars shot and killed an Amish man. The man’s father was devastated and wondered how he would go on, but brought himself to visiting the killer in prison and extending his forgiveness. The judge passed a death sentence, which was commuted with hours to spare by the Governor because once again the Amish flooded his office with letters asking for the death sentence to be revoked.

- Some teenagers throwing stones at an Amish family to harass them inadvertently killed their infant. The father said,”if I saw the boys who did this, I would talk good to them. I would never talk angry with them or want them to talk angry with me. Sometimes I do get to feeling angry, but I don’t want to have that feeling to anyone. It is a bad way to live.”

Finally, the authors reply to the expected rejoinders; for example that such forgiveness is naive. I’m surprised at how many people there are in 2025 for whom the first response to this kind of moving event is to immediately question or challenge its virtue, as if it denies justice. For example, I remember hearing negative responses to the live-action remake of Cinderella, which ends with her forgiving the evil stepsisters. Yes, such forgiveness is difficult and should not be demanded by outsiders who don’t know what they are going through, and yes, we should still protect ourselves from further harm even if we have forgiven people, and yes, as Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, we shouldn’t expect some demographics to exercise pacifist forgiveness like Martin Luther King Jr., while lionizing the violent resisters of other groups like William Wallace and George Washington, but all that aside you have to be really be beyond feeling to see the reaction of the Amish as more dark than light (and this is coming from somebody who is very pro-death penalty).

So this book is going on my “required reading” list for my children (and yes, I know I’m being foolishly optimistic that my children will read the entire “required reading” list before they graduate) as a how-to guide for radical forgiveness, both its New Testament-rooted theology as well as what it actually looks in real life like when vectored through a kind of primitive Christian simplicity, without the “sophisticated” cynicism of modernity.

Comments

5 responses to “The Amish and Radical, Decisional Forgiveness”

My question is how do the Amish reconcile this concept of “radical forgiveness” with the practice of shunning their own members who transgress Amish rules or leave the sect.

They actually talk about that in some depth, and I learned something new. Some people call the practice “shunning,” but it’s not “you’re dead to me” shunning a la Fiddler on the Roof where they can’t talk or meetup with family members who have left. It is true that there are some parameters; Amish can’t take money or rides from those who leave, and there are some kind of conditions about which meetings those who leave can attend, but the idea that they cut off all contact and disown leavers is false.

I wonder how much that varies according to the strictness of the specific group. I’ve been following the stories of several former Amish on social media, and the shunning they have described has been severe and extremely painful, even driving one man to suicide.

That’s a real possibility since there’s no Correlation Committee for the Amish and there is a lot of variation among groups. The Swartzentruber Amish in particular could be guilty of the kind of thing you’re describing.

It’s discouraging to see our society give up on Jesus’s harder teachings, even as ideals. (A fairly establishment columnist in our local paper had a column this morning explicitly defending schadenfreude.) You might think this was due to the declining fraction of Christians, but self-proclaimed defenders of Christianity have made “retribution” their watchword.

I can see where people like Coates are coming from though–too often people have been pressured to compromise on their safety or excuse ongoing oppression in the name of forgiveness. Forgiveness, like justice, looks backward: justice says “You must suffer for what you did (whether you have changed since or not)” while forgiveness says “I don’t want you to suffer for what you did to me (whether you have changed since or not).” It’s entirely consistent with forgiveness to also look forward and say “But I’m not going to let you do it again.” In cases of abuse, for example, that might have to take the form of “But you can no longer be part of our family.” That’s not a punishment, and it’s not being unforgiving. It’s prioritizing safety.