Category: New Testament

-

Was Jesus Married? Where Was He Born? The Restored Gospel and the Quest for the Historical Jesus

Now that I’m trying to avoid creating AI depictions of deity I feel like a Muslim. The “Quest for the Historical Jesus” is a scholarly endeavor to try to suss out details about Jesus’ life from a naturalistic worldview without any religious priors. Given the extreme scarcity of hard data you have to think deep…

-

The Restored Gospel, the Great Apostasy, and the Didache

About a year ago I read and wrote a post on 1st Clement, arguably the earliest Christian document outside of the New Testament. I finally got around to reading the Didache, a Christian treatise that is also in the running for oldest authentic Christian document after the apostles (the confidence intervals for the documents coming…

-

Gold-Star Converts and the Parable of the Wedding Feast

On our missions a lot of us gave lessons to some professor or such and were excited at the prospect of a well-thought out, high powered intellectual convert. And we’re not the only ones, I suspect Catholics love to talk about John Henry Newman for this reason. The idea, especially for them, is that you…

-

Early Christians, Female Ordination, “The Same Organization That Existed in the Primitive Church,” and Current Offices

The 6th Article of Faith can be interpreted along a continuum. On one extreme you might have a super strict interpretation that holds that Jesus had deacons, teachers, priests, and elders quorums, the whole bit, and on the other side, which I’m more partial to, is that Article of Faith 6 is true in a…

-

Jesus Christ as a Literary Subject

The Ascension Lately I’ve dipped into literary depictions of the Savior’s life. Unsurprisingly given the subject matter, historically responses to literary depictions of the Savior have been quite polarizing, and sometimes controversial. For example, evidently The Man Born to Be King, an early, relatively milquetoast (by today’s standards) radio depiction of the Savior’s life, was…

-

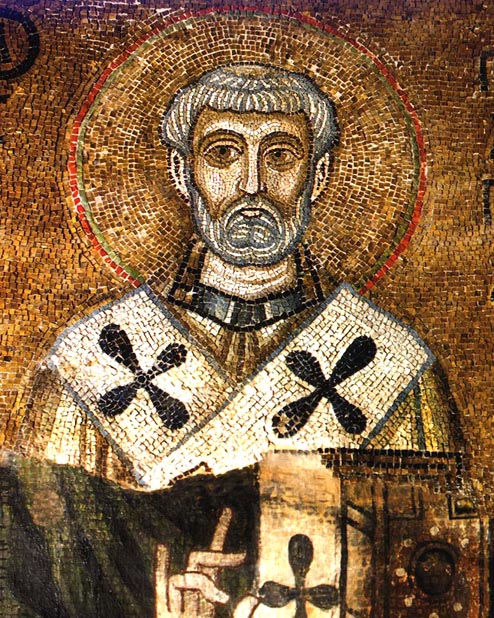

The Restored Gospel, the Great Apostasy, and St. Clement

I finally got around to reading the Epistle of 1st Clement. Written by Clement of Rome (or, as bishop of Rome, Pope Clement I if you’re Catholic), 1st Clement represents one of the earliest if not the earliest authentic Christian document after the apostles. There has been a lot of back-and-forth about the nature of…

-

On Overreliance on Specific Bible Translations

One aspect of Islam that I appreciate is their approach to translation of scriptures. You see, the Quran is considered a sacred text that was originally revealed in Arabic, and translations into other languages are often called “interpretations”. This is because Muslims believe that the Quran’s sacred character is unique to the Arabic language, and…

-

Historical Narratives and the Pharisees

Growing up in the Church, I repeatedly heard stories where missionaries encountered people who had been reading anti-Mormon literature and told them that “you wouldn’t decide on which car to buy by reading only the stuff put out by a company’s competitors – you would also read what the company that produced the car has…

-

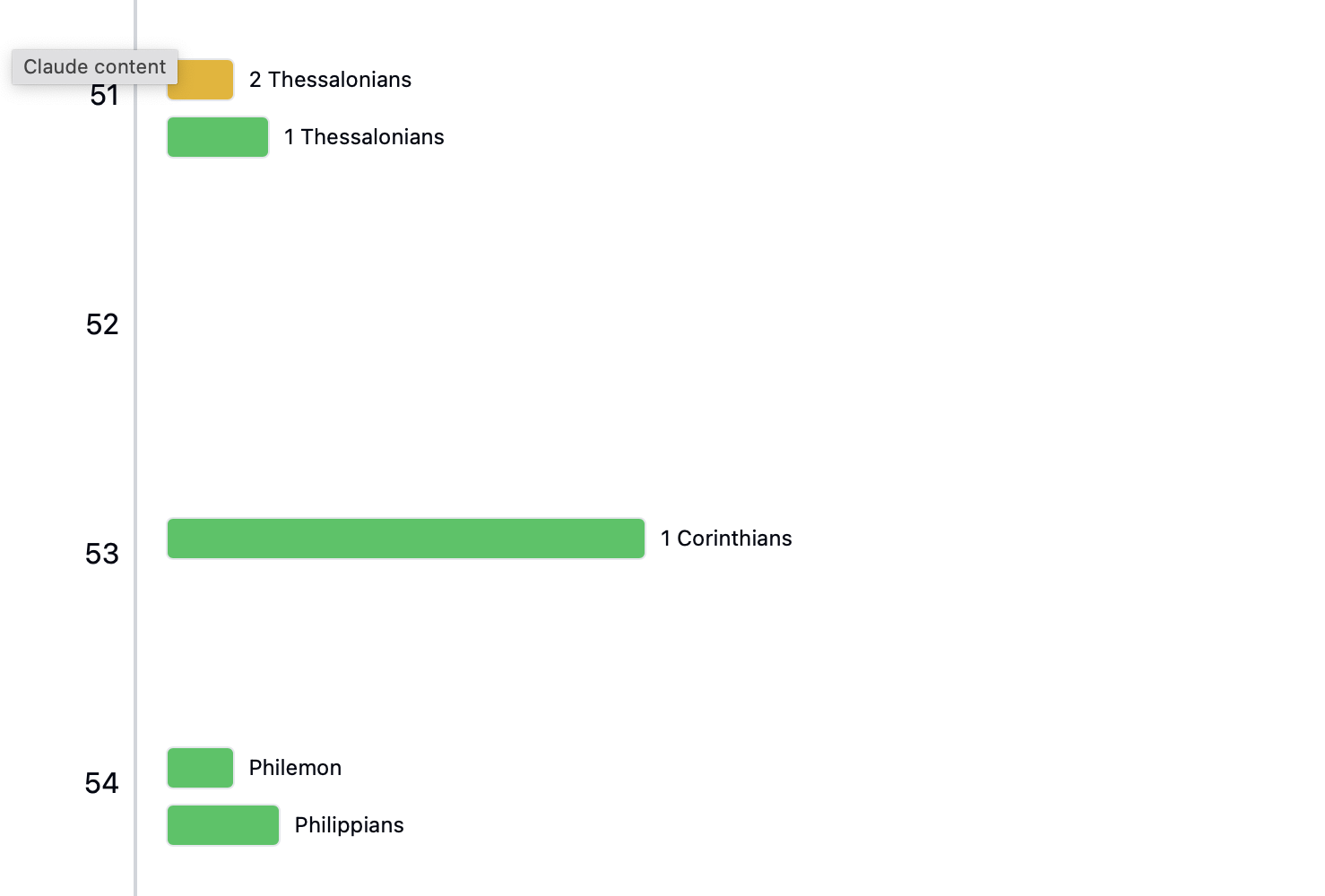

Data Visualization of New Testament Books by Size, Time Since Christ, and Authenticity

A part of the graph, the link below has the whole thing. Of the big AI players, Anthropic’s Claude is quite good at making diagrams, so I used it to generate an infographic I’ve always wanted to see, something that conveys in one visual how far away from Christ a book in the NT was…

-

Misuse of the “Lost Sheep” Parable

People often misuse the Parable of the Lost Sheep, where the Lord leaves the 99 to go after the 1, and draw analogies and connections that don’t make a lot of sense given the premises of the Parable, so I thought I’d make a set of guidelines for logically using the Parable. Note: I have…

-

You Might Be a Pharisee if…

The Pharisees get a bad reputation from their portrayal in the gospels, but it probably isn’t deserved. Jewish scholar Amy-Jill Levine recently discussed why that is likely to be the case that we are guilty of misunderstanding the Pharisees in a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog From the Desk. What follows here…

-

Septuagint

When Jesus and the early Christians talked about the scriptures, they were using a version that is different from the manuscript basis of most English translations, including the King James Version that is so often used in Latter-day Saint circles. In a Hellenistic world, they relied on the Septuagint—a Greek translation of the Tanakh (Old…

-

Notes on Revelation

[As I was going through my files, I found this draft that written four years ago. As it has about 24 hours of relevance left, I’m publishing it now. Happy New Year.] When I teach Revelation 1-11 to my youth Sunday School class, I’ll probably start off by saying something about gasoline.

-

Thomas Wayment on the KJV

Why do Latter-day Saints regard the King James Version as the official English translation of the Bible for the Church? It’s a question that has been asked many times by different people, especially since there are translations in modern English that have a better textual basis in Greek manuscripts. In a recent co-post at the…

-

Jesus’s Female Ancestors

Jesus the Messiah was the son of a righteous and godly woman named Mary, through whom he had many ancestors discussed in the Hebrew Bible. Among those were several remarkable women. In a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog, Camille Fronk Olson discussed some of the women in the genealogy of Jesus. What…

-

The Bible and the Latter-day Saint Tradition: A Review

The Bible and the Latter-day Saint Tradition, published by University of Utah Press, is an impressive collection of information about Bible studies and how Latter-day Saints interact with the Bible.

-

“Like a wise man who built his house on rock”: A Pioneer Day Homily on Matthew 7:21-27

A sacrament meeting talk given 23 July 2023 At the conclusion of the Sermon on the Mount, St. Matthew recorded that the Lord, Jesus Christ stated: “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven. On that…

-

The Jewish Revolt and the Abomination of Desolation

One of the more pivotal events in the development of both Christianity and modern Judaism was the First Jewish Revolt, which started in 66 CE and culminated in the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. In a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog From the Desk, Jared W. Ludlow discussed this…

-

Camille Fronk Olson on Women in the New Testament

The Bible is “the bedrock of all Christianity” and women play some very key roles in the stories that it shares. Camille Fronk Olson has worked to highlight these female Bible characters as a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog From…

-

Herod the Great as the Messiah

A repeating theme in Second Temple Judaism is the expectation for a political messiah that would rule Judea. While Christians are aware of this primarily through the expectations that Jesus of Nazareth encountered during his ministry, there are many other people who tried to fulfill that role. Herod the Great may have been one of…

-

Who was Mary Magdalene?

Mary Magdalene is a well-known figure in the New Testament whose life has been the subject of speculation and storytelling for much of Christian History. One of the more recent instances of this is The Chosen. In a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog, From the Desk, Bruce Chilton discussed Mary Magdalene, offering…

-

The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints, Revised Edition

Thomas Wayment’s The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints, Revised Edition is an exceptional resource for anyone, and particularly a Latter-day Saint, interested in studying the New Testament from a fresh and modern perspective through its clear and readable translation, insightful commentary, and expanded introductory material. One of the standout features of this book…

-

Thomas Wayment on New Testament Canonization

An interesting point made by the late Eastern Orthodox bishop Kallistos Ware is that the books that were selected to be contained in the Bible are a tradition that developed within and passed on by the Proto-Orthodox Church. The process by which that tradition solidified into official canon was a gradual (and messy) one. In…

-

What You Might Be Missing in Matthew’s Genealogy of Jesus

“Most readers of Matthew’s Gospel take one look at that first page full of ‘begats’ and impossible-to-pronounce names and quickly turn the page.” So begins Julie Smith’s thoughtful essay “Why These Women in Jesus’s Genealogy?”, which is available free of charge in the Segullah journal (2008) and is reprinted in her book Search, Ponder, and…

-

When Was Jesus Born?

When was Jesus born? While not consequential to our salvation or daily choices, it’s an interesting question to explore. In a recent interview at the Latter-day Saint history blog From the Desk, Jeffrey R. Chadwick discussed his research into the question: When was Jesus actually born? What follows here is a co-post to that discussion…

-

Ancient Christians: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints

The Maxwell Institute at BYU recently published Ancient Christians: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints, and it is a fantastic journey into early Christianity geared specifically to Latter-day Saints. Through a collection of 14 essays dealing with topics ranging from praxis and worship to scripture and theology, the key elements of Christianity during its first several…

-

If I Didn’t Believe, Part II: God, Jesus, and Other Religions

God: I feel like the belief in God is one of those almost congenital predispositions; you either believe or you don’t. Empirically, based on fine tuning and the complexity of the origin of life, I would lean towards there being an organizational force, even in the absence of a belief in the Church. Additionally,…

-

Book Report-Veritas: A Harvard Professor, A Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife

This is a well-written journalistic account of a scandal that happened in the biblical studies community in 2012 when a purportedly ancient parchment surfaced that contained the words “Jesus said to them ‘my wife.’” Despite some red flags such as bad Coptic grammar, Professor Karen King, one of the preeminent scholars in the field, became…

-

Was Jesus Married or Not?

An enigma that has been explored repeatedly over the years, both in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and in Christianity more broadly, is the marital status of Jesus of Nazareth. There is little to reliably indicate either way in the established canon of the New Testament, but that hadn’t stopped people from…