Category: Book Reviews

-

Temples in the Tops of the Mountains

Temples in the Tops of the Mountains: Sacred Houses of the Lord in Utah by Richard O. Cowan and Clinton D. Christensen (BYU RSC and Deseret Book Company, 2023) helped me solve a long-time mystery about my life. You see, when I was six years old, I went to the Vernal, Utah Temple open house.…

-

The Heart of the Matter: A Review

The Heart of the Matter, by President Russell M. Nelson, is a book to live by. It serves as a collection and presentation of his core messages as president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and provides guidance for both belief and living as a member of that church.

-

Sins of Christendom: A Review

Anti-Mormon literature is always a touchy subject, but Sins of Christendom: Anti-Mormonism and the Making of Evangelicalism by Nathaniel Wiewora handles it deftly, putting it in a broader context of change and debate within Evangelical Christianity.

-

American Zion: A Review

If I were to ever write a single-volume history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I hope that it would turn out like Benjamin E. Park’s American Zion: A New History of Mormonism (Liveright, 2024). It is a very nuanced, insightful, and well-written take on Latter-day Saint history in the United States.…

-

The Testimony of Two Nations: A Review

The Testimony of Two Nations: How the Book of Mormon Reads, and Rereads, the Bible by Michael Austin (University of Illinois Press, 2024) is a delightful and insightful venture into the ways in which the Book of Mormon interacts with the Bible.

-

No Division Among You: A Review

No Division Among You: Creating Unity in a Diverse Church, ed. Richard Eyre (Deseret Book, 2023) is a beautiful book in its intentions and efforts. The book is a collection of 14 essays that discuss ways to view the need for unity while embracing diversity. Each essay is by a different author, bringing in diverse…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Review: A Life of Jesus, by Shusaku Endo

A Life of Jesus is an introduction to the life of Christ by renowned Catholic Japanese novelist Shusaku Endo, the author of Silence, a book set during the early persecutions of Christians in Japan. Much of Endo’s work revolves around the tensions of being a Catholic in a very non-Christian country, and this book was written…

-

A Word in Season: Isaiah’s Reception in the Book of Mormon (A Review)

A Word in Season: Isaiah’s Reception in the Book of Mormon by Joseph M. Spencer (University of Illinois Press, 11/21/2023) is a scholarly exploration into the interplay between the biblical prophet Isaiah and the narrative fabric of the Book of Mormon

-

Latter-day Saint Perspectives on Atonement – A Review

Latter-day Saint Perspectives on Atonement is a fascinating journey through the scriptures and teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints about the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

-

Chad’s Top 10 Book List from 2023

In case it’s of use to anyone, I’ve prepared a list of my top 10 books that I’ve read this last year. (That can include books that were not published within the last year, though the majority of them were published in 2023 or 2022):

-

Stay Thou Nearby: A Review

The 1852–1978 priesthood and temple ban on Blacks in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a bitter pill to swallow, especially for those affected most directly by it. I have been grateful, however, for efforts in the Church to address the issue more openly in recent years, including several publications from Deseret…

-

Lowell L. Bennion: A Mormon Educator, a Review

I have to say that I’m a fan of the trend towards short, accessible biographies of notable figures in Latter-day Saint history. Between University of Illinois Press’s “Introductions to Mormon Thought” series and Signature Books’s “Brief Biography,” there is a lot of excellent work being published. One of the most recent, Lowell L. Bennion: A…

-

Diné dóó Gáamalii: Navajo Latter-day Saint Experiences in the Twentieth Century: A Review

Alicia Harris—an Assistant Professor of Native American Art History at the University of Oklahoma—wrote that “If the LDS Church really can work for all peoples, we need to more attentively listen, hear, and be represented by a much greater variety of voices. We must more actively prepare a place for dual identities to be touched…

-

Like a Fiery Meteor: The Life of Joseph F. Smith: A Review

Joseph F. Smith (1838–1917) is a towering figure in Latter-day Saint history, so I have waited and hoped for an academically rigorous biography about him for years. Stephen C Taysom delivered on that hope this year in Like a Fiery Meteor: The Life of Joseph F. Smith.

-

Review: Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye, “Sacred Struggle: Seeking Christ on the Path of Most Resistance”

Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye’s new book, Sacred Struggle: Seeking Christ on the Path of Most Resistance, confirms her status as reigning queen of great subtitles. It also confirms her status as one of our tradition’s most insightful pastoral-ecclesiological thinkers, worthy heir to the great Chieko Okazaki. Melissa has the professional training, the personal background and experience,…

-

Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Review

Richard Lyman Bushman’s Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History (Oxford University Press, 2023) is an important contribution to Book of Mormon studies. As a cultural history of the gold plates, the book traces the story of the plates and the translation of the Book of Mormon, reactions to the story and the development of…

-

Harold B. Lee: Life and Thought: A Review

Harold B. Lee: Life and Thought by Newell G. Bringhurst (Signature Books, 2021) is a highly affordable and readable biography of one of the most influential figures in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although his tenure as president of the Church was short, Harold B. Lee had already reshaped…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Review: Saqiyuq, Stories from the Lives of Three Inuit Women

Saqiyuq is an oral history of three generations of Inuit women who lived on Baffin Island near Greenland. Of particular interest to me was the grandmother matriarch’s history, since, born in 1931, she provided a first-hand account of the transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle where people starved or not depending on the ebb and flow…

-

Let’s Talk about Science and Religion – A Review

Back when I was studying biological engineering in college, I remember one Sunday where a stake high councilor came and spoke in our ward. He based his remarks on Elder Quentin L. Cook’s talk “Lamentations of Jeremiah: Beware of Bondage”. When he discussed how “Turning from the worship of the true and living God and…

-

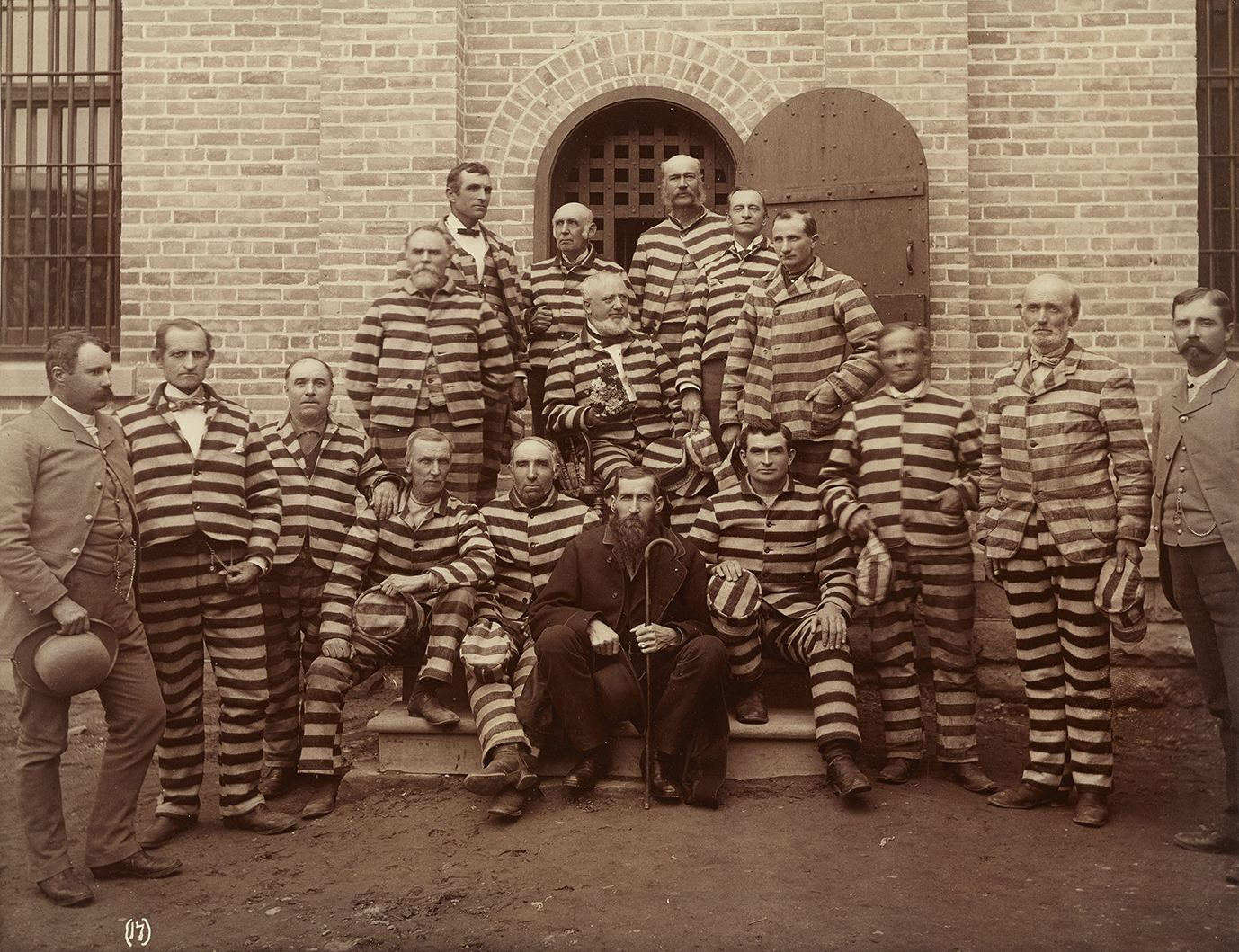

George Q. Cannon: Politician, Publisher, Apostle of Polygamy: A Review

George Q. Cannon: Politician, Publisher, Apostle of Polygamy by Kenneth L. Cannon II is an entry in the Signature Books brief biographies series focused on one of the most influential and best-known Latter-day Saints in the 19th century. As a missionary, publisher, representative for Utah Territory to the United States Congress, businessman, apostle, and long-term…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Review: Seizing Power, The Strategic Logic of Military Coups

Seizing Power by political scientist Naunihal Singh is the preeminent scholarly work on coups d’etat. In it, Singh pairs in-depth investigations of coup attempts in Africa and Russia with a quantitative analysis of correlates of successful coups worldwide. He finds that coups can largely be characterized as coordination games, where military commanders often join…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Review: The Top Five Regrets of the Dying

Regrets of the Dying The Top Five Regrets of the Dying was a bestselling book by a palliative care nurse who spent a lot of time with patients as they were passing away. I’m not going to recommend it as a book; the writing isn’t the best and it gets kind of repetitious, but the idea…

-

The Bible and the Latter-day Saint Tradition: A Review

The Bible and the Latter-day Saint Tradition, published by University of Utah Press, is an impressive collection of information about Bible studies and how Latter-day Saints interact with the Bible.

-

Joseph Smith and the Mormons: A review

Joseph Smith and the Mormons, by Noah Van Sciver, is a fantastic addition to Mormon literature. And while not written as devotional literature, this graphic novelization of Joseph Smith’s life is very well-researched and makes a lot of effort to portray things in a fair and open manner. And the book itself is beautiful in…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Review: Merchants in the Temple; Inside Pope Francis’s Secret Battle Against Corruption in the Vatican

The story of the Vatican Bank and Vatican finances in general is a bit of a wild ride, the kind of thing can get you lost down Wikipedia rabbit holes for hours. I suspect the fact that the Vatican is its own state, combined with the fact that it’s managed by a coterie of clergy…

-

Vengeance Is Mine

The story goes that J. Golden Kimball was once preaching to a crowd in the South and became concerned when he noticed that only men were present. As he opened his mouth to talk, however, All at once something came over me and I opened my mouth and said, . . . ‘Gentlemen, you have not come…

-

Voice of the Saints in Mongolia

Voice of the Saints in Mongolia by Po Nien (Felipe) Chou and Petra Chou is an informative account of the establishment and growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Mongolia. As the first comprehensive history of the Church in Mongolia, the book breaks historical ground and provides valuable insights into the…

-

Let’s Talk About Race and Priesthood

Let’s Talk About Race and Priesthood by W. Paul Reeve is a thought-provoking and insightful book that explores some key aspects of the intersection of race and religion in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To me, this volume is up there with Brittany Chapman Nash’s Let’s Talk About Polygamy…

-

The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints, Revised Edition

Thomas Wayment’s The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints, Revised Edition is an exceptional resource for anyone, and particularly a Latter-day Saint, interested in studying the New Testament from a fresh and modern perspective through its clear and readable translation, insightful commentary, and expanded introductory material. One of the standout features of this book…

-

My Lord, He Calls Me

To say that My Lord, He Calls Me: Stories of Faith by Black American Latter-day Saints, ed. Alice Faulkner Burch (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 2022) is an important collection would be an understatement. While small (clocking in at 225 pages), the volume contains around 35 chapters written by Black American Latter-day Saints, including…