Author: Stephen C

-

On Really Smart People and the Gospel

Growing up in 1990s Orem the figure of Hugh Nibley held a sort of symbolic significance that was greater than the sum of his scholarly parts. The not-so-subtle subtext of the myriad anecdotes about his prodigious memory and learning is “see, if this really smart person believes it, then there must be some really good…

-

When is Somebody’s Belief a Valid Question?

Jack Dempsey Having Some Fun with Harry Houdini The term “Jack Mormon” was popularized by world champion boxer Jack Dempsey who, while born in the Church and remaining friendly towards it, wasn’t a practicing Latter-day Saint (sidebar, while a certain segment of Mormondom gets super excited every time one of us makes it into the…

-

We Humans Had a Good Run

This is a talk written by artificial intelligence; specifically, OpenAI’s new, much more developed GPT-3 that just dropped based on the prompt “Write an LDS talk about overcoming adversity” (it’s shorter, but that’s just because I set the word limit relatively low). Good morning brothers and sisters. I am so glad to be here with…

-

If I Didn’t Believe, Part IV: Meaning, Purpose, and Life in the Void

Dying Universe Morality In the absence of a faith I don’t think I’d have very strong opinions about abstract or moral concepts. This isn’t one of those “if you don’t believe why don’t you kill your grandma?” arguments that make good-hearted atheists roll their eyes. I have no desire to kill grandmas regardless of my…

-

If I Didn’t Believe, Part III: Living a Non-Latter-day Saint Life

Word of Wisdom I accidentally drank beer once, and found it gross. I’ve been told that it’s kind of an acquired taste, so given the harms it does I probably just wouldn’t acquire it even if I didn’t have any religious scruples about doing so. However, I like new experiences, so I’d probably try…

-

On Pro-Choice Deadbeat Dads

Note: This post was inspired by some recent media attention that has been given to a Latter-day Saint author for a book in which she talks about how the abortion debate should recenter on “ejaculating responsibly.” I haven’t read the book and therefore don’t have a right to critique its particulars, but here I’m addressing a…

-

If I Didn’t Believe, Part II: God, Jesus, and Other Religions

God: I feel like the belief in God is one of those almost congenital predispositions; you either believe or you don’t. Empirically, based on fine tuning and the complexity of the origin of life, I would lean towards there being an organizational force, even in the absence of a belief in the Church. Additionally,…

-

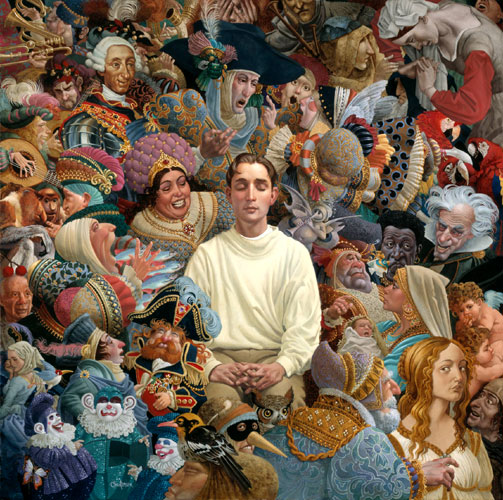

If I Didn’t Believe, Part I: The Joseph Smith Trilemma, the Book of Mormon Translation, and the Witnesses

Like a lot of people who have gone through faith crises, I’ve spent some time thinking through the alternative to belief in the Church’s truth claims. If we assume that the Church isn’t what it says it is, what is the best explanation for the Church and its related claims that make sense of the…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Report on “Sex Cult Nun: Breaking Away from the Children of God, a Wild, Radical Religious Cult.”

One of the accusations you occasionally get from the far corners of the internet is that the early Church was a “sex cult” because of Nauvoo-era polygamy. That accusation, of course, begs the question of what a sex cult is. While I categorically don’t like to use the word “cult,” (for, among other reasons, implying…

-

Nepotism in High Church Offices

Nepotism is the most natural of vices and needs to constantly be proactively guarded against, or else it will almost certainly creep into any large institution. In the early Church there just weren’t a lot of options to choose from because it was so small, but as the Church becomes larger and more diverse it…

-

General Conference as a “Peaceable Thing of the Kingdom”

The Listener, by James Christensen I’ve been as guilty as anyone of, subconsciously and in the back of my mind, looking forward to General Conference more for the big announcements or controversy than the spiritual nourishment. Reading about the controversy and ensuing outrage (and counter-outrage) in particular are kind of an emotional crack cocaine for…

-

General Conference and Our Shrinking Attention Spans

As the father of a lot of small, messy children, I easily listen to two hours of podcasts a day while cleaning (how my parents’ generation cleaned before podcasts I have no idea). The other day a movie producer on a podcast made a comment about how, in the days before streaming, television producers would…

-

BYU Professors Calling the Brethren Autocratic Fascists is Not Going to Help Anybody

At a recent post over at BCC, a tenured BYU-X professor communicates some anxiety about CES’ new direction, which is certainly their right, but in doing so the author calls the people who made this decision (i.e. the brethren, if that wasn’t clear from Elder Holland’s talk) autocrats, and prominently displays the fasces at the…

-

Rest in Peace Rodney Stark

I was recently informed that Rodney Stark passed away. For the uninitiated, Rodney Stark was a force of nature in the sociology of religion. His interests ranged from early Christianity to UFO movements, and agree with him or not, he was a giant in every field he engaged. His theories helped shape the strategies of…

-

Latter-day Saint Book Report on “The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara”

In 1857 officials raided a home in the Jewish ghetto in Bologna, Italy and forcefully removed a 6-year old child based on the testimony of a servant that he had been baptized as an infant and was, therefore, Christian. At the time Bologna was under the direct rule of the Pope (back in the day…

-

Book Report-Veritas: A Harvard Professor, A Con Man, and the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife

This is a well-written journalistic account of a scandal that happened in the biblical studies community in 2012 when a purportedly ancient parchment surfaced that contained the words “Jesus said to them ‘my wife.’” Despite some red flags such as bad Coptic grammar, Professor Karen King, one of the preeminent scholars in the field, became…

-

Update on Bisbee Case

Since I last posted on this, 1) Mormonr published the testimonies of the two bishops involved in the Bisbee case, and 2) the Church came out with their follow-up statement. For point # 1, contrary to the testimony of the law enforcement agent, both bishops indicate that they only knew about a one-off case of…

-

The Ubiquity of Temple Worship Among God’s Children

I was privileged to attend the recent dedication of the Washington, DC temple, during which I got thinking about the common themes in temple worship across time and cultures. I’ve always been vaguely aware of these similarities, but I went down the Wikipedia rabbit hole and spent so much time down there that I thought…

-

The Bisbee Case: Where Was the Failure Point?

Like a lot of you, I felt nauseated after reading the AP article that recently dropped, and have been following the story since. There’s always a temptation when something like this happens to give an off-the-cuff hot take, but it was clear that there was a lot to this story to unpack and I didn’t have…

-

Three More Points About That Picture

After the initial splash of the purported Joseph Smith photo being revealed there have been various strands of takes, two of which I thought worth briefly addressing. Also, there’s one more point I haven’t seen anybody address but thought I should raise. He’s too old! I’m surprised at how many people, some of them rather…