Author: Jesse Hurlbut

-

Hurlbut’s Story of the Bibles

Jesse Lyman Hurlbut, a Methodist minister, first published the Hurlbut’s Story of the Bible in 1904. In the book, he retells 168 Bible stories in simplified modern English prose. The author’s purpose was to provide a version of key scripture passages that young readers would find accessible. The numerous republished editions that have appeared throughout…

-

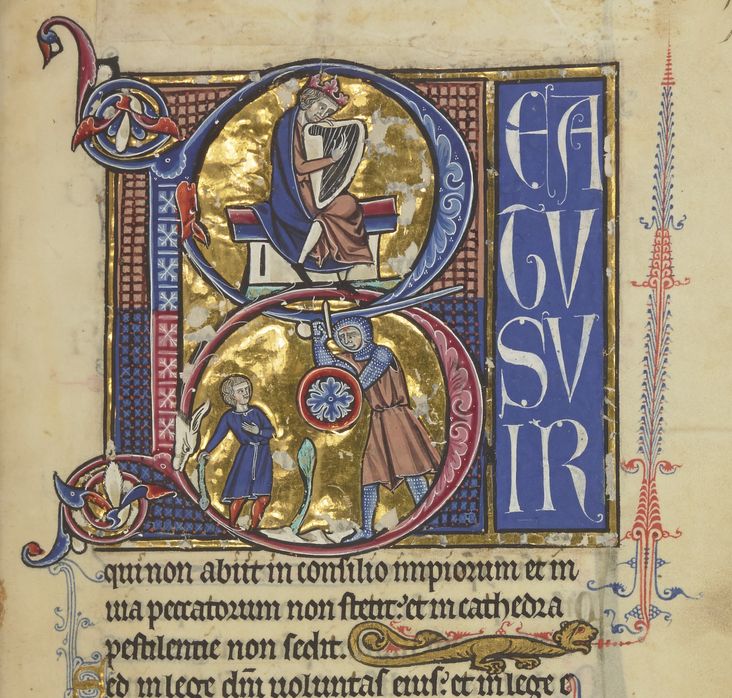

Beatus Vir

Throughout the middle ages, the popularity of the Book of Psalms caused it to be reproduced in Latin as a separate volume of devotional literature called the Psalter. In medieval manuscripts, the opening phrase of Psalm 1, “Beatus vir,” was often richly decorated, as in this example from the thirteenth-century. The Latin Beatus is related…