The New Testament is basically contradictory about the divine nature of Christ. On one hand Christ clearly talks to God as a separate being and identifies his will as being separate from God’s (Luke 22:42), but elsewhere he refers to himself as the Father in a very literal, I-am-physically-the-same sense (John 14:8-14). And then we have the issue with the fact that two divine beings (if we assume that Christ is both divine and a distinct person from God)=polytheism. So in the end your take on the Trinity or godhead comes down to which bullet you are going to bite. We bite the one that technically, in a sense, makes us polytheists which, for traditional Judeo-Christian faith that is heavily influenced by the post-Persian exilic period, is the ultimate heresy, but hey, maybe if you wear it long enough you’ll get used to it.

However, I don’t begrudge other traditions or people coming to different conclusions and biting different bullets in an effort to essentially square the circle of all the different New Testament accounts of Christ. While I don’t subscribe to Nicaean Christology I don’t have a particular problem with it; you have to figure out some way to make it all fit.

No, my problem with Trinity-talk deals with the meta-discourse surrounding it and the supposed implications of subscribing or not subscribing to it.

First, one often hears that nearly everybody in Christendom believes in the Trinity because it is so clearly in the scriptures. As to the first part, it is true that there is a fairly strong Nicaean consensus across different traditions now. (Of course, there are variations within Nicaean Christology, such as with the filioque phrase that the Catholics believe but the Orthodox do not, but the basics are indeed remarkably consistent across Christendom.

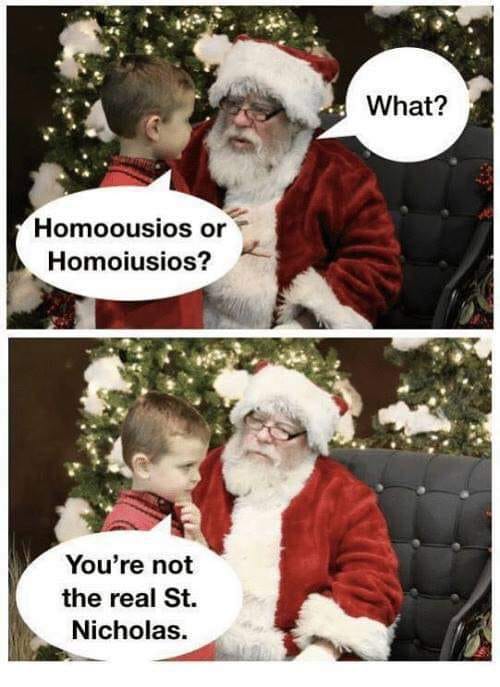

However, the contentious theological battles pre-dating Nicaea on this question among very smart scripture scholars militates against the idea that the trinitarian reading is the patently obvious one, or that its widespread adoption is somehow evidence of its patent truth; that the text doesn’t allow other plausible interpretations.

What made the Nicaean model the consensus wasn’t the force of argument as much as the force of the Roman sword. That doesn’t make it wrong of course, but it problematizes the idea that that’s the obvious take for anybody who reads the Bible closely. Even in our own day (more or less) one of the smartest biblical exegetes of all time (as in, smartest person who happened to be a biblical exegete, not that his takes were the smartest necessarily), Isaac Newton, arrived at an essentially non-trinitarian, Arian view of God through his own bible study.

Second. I understand and am fine with a highly esoteric, technical/philosophical distinction being made by a faith. I see where they are coming from. Even if you use the right name, how do you know that that’s the right God? What are God’s defining characteristics? There clearly have to be some parameters or else somebody could claim that their dog they worship is Yahweh and claim to be Jewish. For an example of this kind of deep dive see the Vatican’s official ruling on Latter-day Saint theology and, by extension, the validity of our baptisms, essentially ruling that, while we use the same names (Jesus, Baptism, etc.), that in terms of the essence of the thing we’re talking about very different things from the Catholics. I get that.

However, my problem with the Trinity hinges on the premise that where if a true belief is considered necessary for salvation then you shouldn’t be required to exercise esoteric, highly technical and specialized reasoning and learning to access it, since not everybody can or has access to such an education. It should be understandable for the vast majority of unlearned human beings (and the ones for which it is not should be exempt, see our informal theology on disabled people under the mental age of 8 and salvation), and the sort of fine-grained Latin distinctions made in formal Trinity discourse that separate the heretics from the true disciples of Christ are way past that mark.

In the case of Protestants it’s even worse since they are sola scriptura, the Catholics at least recognize another layer of authoritative interpretation that you can rely on even if the primary sources and analysis are beyond you, but in the Protestant case you are in principle being judged based on scripture alone, but on something that is not patently obvious from a surface reading of said scripture and was only resolved after centuries of highly technical theological debate and, again, imperial enforcement. If you are going to be judged for eternal damnation or eternal rest based on your understanding of what the scripture says, then to be fair the scripture better be pretty dang clear on that point, when with the Trinity it is not.

Comments

12 responses to “My Problem with the Trinity”

“We bite the one that…”

Who is “We”? I think maybe there is some diversity in thought on this matter even among Latter-day Saints.

That said, I agree that a perfectly “correct” understanding is not required. What is asked for is faith in Jesus Christ and some measure of charity.

I think this is an important point: “if a true belief is considered necessary for salvation then you shouldn’t be required to exercise esoteric, highly technical and specialized reasoning and learning to access it.” (It’s also one of the reasons that I don’t put much stock in triple-bank-shot readings of the Book of Mormon that find its real message is something only someone with a graduate degree can figure out.)

We should not, however, cop to being polytheists. There are a lot of highly pernicious downstream effects of that that are still relevant today. The precise formulation of what we really mean (“one in purpose,” etc.) is worth the effort, even if the end result isn’t wholly satisfying and can end up looking a lot like a creed.

Take a look at Social Trinitarianism. God is defined as a loving, unifying relationship of three persons (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) and the effects that relationship has on the natures of those persons. It makes a bit more sense to me than traditional Trinitarianism, especially if one looks through framework of Process Theology.

I think that part of the contention is the view point that there’s monotheism and there’s polytheism and that’s all that there can be. There isn’t room in that view point for a team of beings functioning together as one. So it takes a bit of thinking to break out of the monotheism vs polytheism constraints.

I think it’s important to start with Section 130. We need a clear understanding that the Godhead is comprised of three separate beings. IMO–if we don’t start there then we’ll go off the rails at some point as we’re trying to understand how they are one.

That said, I think–as Old Man has pointed out–that a Social Trinitarianism of sorts comes closest to what we learn from the restored gospel about the nature of the Godhead–how they work together and so forth. Where it fails is in simply not going far enough. But, then again, that might take us into things that are beyond our ability to comprehend–so it’s good as far as it goes.

Ji: Sure, there is some diversity like there is with anything, but I suspect that inasmuch as there is any diversity it is stemming from cultural Latter-day Saints who hold to a more secular version of Christ, and not from Latter-day Saints who are secretly Protestant Nicaeans, although I might be wrong.

Jonathan: Sure, it hinges on how you define “polytheism.” If we get past the knee-jerk reaction against polytheism and really think about why classical polytheism is inferior to monotheism, it’s because classic polytheism has a pantheon of Gods often at variance with each other, so there was no One True Way, but just competing powers-that-be. Making it clear that Christ, Heavenly Father, Heavenly Mother, what have you are all one in purpose and will takes care of that problem.

Old Man: Interesting, I’ll have to look into that. (Admittedly I’m not super versed in the different variations on Trinitarian theology, but to my point in the OP, I shouldn’t have to be).

Jader3d: I agree, and to some extent that’s what I’m trying to flesh out in my response to Jonathan above.

Jack: I agree, D&C 130 is really quite ground shaking yet simple and understandable.

I wonder how much early Christianity was influenced, even warped, by the need to distinguish itself from the polytheism of the day: endlessly explaining that Jesus was a God, but not at all in the same way as Augustus Caesar, and the Son of God, but not at all in the same way as Hercules. And the God of everyone, not just the Jews. And not at all similar to the fallible, fickle gods of Homer or Ovid–the God of the Greek philosophers was closer to the truth in many ways (paging Stephen Fleming).

I’m thinking back to my youth, when many members were so eager to distinguish us from evangelicals that they came close to denying the grace of Christ.

It’s true that the Bible doesn’t support Trinitarianism in any very explicit way. Fortunately, the Book of Mormon remedies that deficiency. :)

The trinitarian verses in the Book of Mormon deserve review and consideration. The LDS theology of God has changed over time.

Stephen,

You mention (1) cultural Latter-day Saints who hold to a more secular version of Christ and (2) Latter-day Saints who are secretly Protestant Nicaeans, but can there also be diversity among (3) true and faithful believing Latter-day Saints? Or does everyone in (3), in order to be included in (3), have to be part of the “We” you described?

I think there is diversity of thought on this matter even among true and faithful believing Latter-day Saints. Thus, for me, your use of “We” to describe a normative belief among Latter-day Saints (and not just the (1) or (2) you describe and dismiss) is problematic.

Sure, there may be trinitarian Latter-day Saints, but our theology is very officially non-trinitarian. Therefore, despite possible variation in this belief I feel comfortable using the “we,” as I would if I were to say “Muslims believe that Mohammad is a prophet,” “Catholics believe that the Eucharist is the literal body and blood of Christ” etc., even though yes, with any religious belief you are going to have variation within that group.

RLD, yes, philosophy was basically a religious reform movement among the Greeks. Philosophers wanted to think about God and morality differently from the traditional Greek religion/myths. Socrates was executed for not teaching the traditional Gods of Athens.