One of the more curious aspects of the temple ceremony was the charge to avoid “loud laughter.” [Note, I originally spoke in the present tense, but evidently it has been removed–with all the recent changes I somehow missed that]. It’s like only eating meat during the winter, one of those things that was indisputably, canonically there but virtually nobody, no matter how conservative, made a point of it.

However, I get the concept even if I’m a little fuzzy on the operationalization: avoid frivolity and light mindedness because reality with all its pain and suffering–and glory–is essentially and fundamentally serious. The other day I was reading through a Wikipedia article on the Russian Famine of 1921 (good hell those people have gone through a lot), and it had a picture of human meat displays, possibly from the human meat markets that sprung up during this time (obviously huge content warning). During this and other times in their history such as the Siege of Leningrad it was a real-life Eli Roth film; you had to be careful about letting your kids out of your apartment less roving bands kidnap and eat them. (And if you were Jewish, much of history was a real-life Purge film, where people could just kill you in.a pogrom [another big CW] if they wanted).

You can see why the Russians aren’t known for their comedy. Life gets so gritty that frivolity almost seems like an affront to reality. Of course sometimes a sort of super-dark, cynical humor helps one survive; Yad Veshem, Israel’s official Holocaust memorial organization, published the book Without Humor We Would Have Committed Suicide where they interviewed Holocaust survivors about humor in the camps as a coping mechanism.

Still, there’s a reason that outside of these very particular coping cases one treads lightly with Holocaust and related humor. Obviously a lot of ink has been spilled about the lines of appropriateness and who can say what when dealing with different topics, but whatever the exact lines it hearkens back to the same concept that misplaced humor has the potential to inappropriately make light of something deadly serious.

And by extension, life and existence is deadly serious, even if some frivolity and humor is okay and even necessary in our day-to-day. However, there is a kind of superficiality that those of us in clean-cut, relatively easy environments can get into. I alluded to this in my post on R-rated movies, where we are at risk for consuming saccharine, didactic content as if it is deeply profound, and I think there is an equivalent in our day-to-day paradigms. For example, while our youth are rightly encouraged to keep journals, for most of us they simply serve as painful reminders of how seriously we took the dumbest things in our teenage years. As you become older and experience more children in hospitals, chronic pain, and unpaid credit card bills, the superficial dross burns away. (On a related note, it is fascinating to watch people near the end of life and to take note of what they focus on.) You can tell a lot about how much life people have lived by what things they get stressed out about. In a Church context, how many people show up to your mission farewell or whether you ever get a leadership calling (Or, in this space, what Elder so-and-so or this or that influencer thinks about what you write).

So I don’t know where the exact balance is. On one hand life is deadly serious, on the other hand we sometimes need the illusion of a silly, comical, not-serious existence, and humor itself enriches life. (It is intriguing to me that the Greek playwrights separated everything into comedy and tragedy, as if the cosmic order of things naturally fell into those two categories.) Plus if we just sat in constant awareness of all the horror we would not be able to sleep at night, so some suspension of disbelief and redirection of thoughts is necessary to be a functional human being that isn’t a nervous wreck.

Joseph Smith was open about his own struggles with this point when talking about how he had been “guilty of levity, and sometimes associated with jovial company, etc., not consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as I had been.” But on the other hand also mentioning that if he kept his mind (bow) strung up all the time it would lose its spring, so in the end I think the day-to-day balance is one of those “I know it when I see it,” spiritually discerned things.Comedy aside, one of the central messages of the gospel is that even with all that the light outweighs the darkness, poignantly described by Mormon when he’s describing his own scenes of rape and cannibalism: “may not the things which I have written grieve thee, to weigh thee down unto death; but may Christ lift thee up,”

Comments

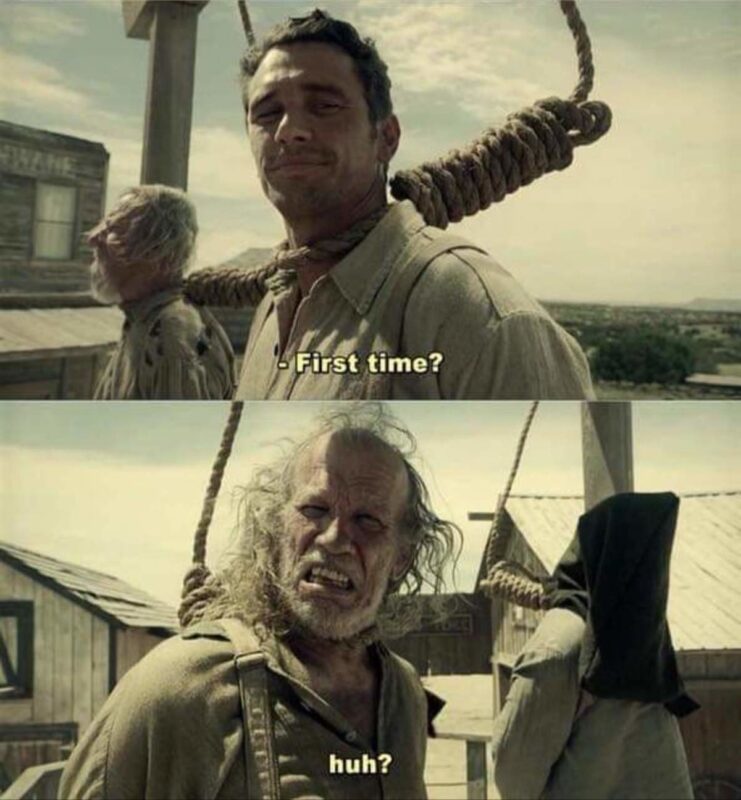

15 responses to “Loud Laughter, Reality, and Gallows Humor”

An interesting coincidence – today’s New York Times contains a brief essay from Pope Francis titles ‘There Is Value In Humor’:

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/17/opinion/pope-francis-humor.html

Fortunately, the charge to avoid loud laughter was removed from the ceremony.

Whoops. Corrected it in the OP.

I guess this makes no sense to me because I don’t find life and existence deadly and serious. I find it joyful, even with the sorrow, and am a fan of Victor Frankl.

Humor is a problem when it is used to hurt others, individually and/or collectively. Humor directed at self is coping. Seeing Humor in life is to see an aspect of God.

The temple ceremony was just wrong on this one. Glad it changed.

The prohibition against “loud laughter” in the endowment occurred explicitly alongside behaviors like “lightmindedness,” “taking the name of God in vain,” and “speaking evil of the Lord’s anointed.” These were collectively described as “unholy” and “impure”—loaded and unmistakable ritual terms that carry specific temple connotations. The context, to me, has always seemed clear: do not profane the sacredness of the temple or your temple covenants. I’ve never understood the handwringing over this—or the dumb ExMo mockery that circulates on TikTok. I guess the change was made because people just missed the point (as evident by the comments here), and it became distracting.

It didn’t say laughter, it said loud laughter. Just as it didn’t say light heartedness, it said light mindedness. People who bray like jackasses could indeed stand to moderate themselves. Nothing wrong there.

Dave C., Thanks for your comment!

Nobody here is saying to avoid laughter and mirth at all. (“Humor itself enriched life,” “some frivolity and humor is okay and even necessary in our day-to-day”) and the use of “light-heartedness” wasn’t a quote from the temple ceremony.

I agree with Stephen. If you hear the wording that replaces “loud laughter”, it’s immediately apparent that loud laughter was referring to making a mockery of sacred things.

It may have been removed from the endowment, but D&C 59:15 and 88:69 are still in the books. But see Eccl. 3:4 (cf. 2:2) and Luke 6:21.

Of course this raises the question of why the endowment, if inspired, would change (and it changes a lot). The whole premise of continuing revelation is that not everything that comes by revelation is eternal unchanging truth: a lot of it is guidance specifics for certain circumstances. Was the original meaning different than how we understand those same words today? If so, do we have any evidence of the term “laughter” being used differently in the 19th century than today? Is it because something about the times and human circumstances has changed such that laughter is less sinful than it used to be? Are there any other possible reasons I’m not thinking of?

I’ve recently been studying humor (laughter – loud or otherwise, light mindedness especially as this is how humor works). I just don’t see the distinctions the same as others.

It seems like the argument is that humor aimed at certain things is wrong because these things MUST be taken seriously only. I disagree with that. As I said before, humor is a problem when it’s used to intentionally injure people. Laughing at things that cause stress/anxiety/pain (such as the previous versions of the temple ceremony for me) is coping, a way to put things in perspective, and find joy.

These were collectively described as “unholy” and “impure”—loaded and unmistakable ritual terms that carry specific temple connotations.

This is a bit off-topic, but I don’t think it’s fair to insist that “unholy” and especially “impure” carry “specific temple connotations” when the brethren have been known to assign them distinctly non-temple connotations. I’m thinking specifically of the early-80s fiasco regarding oral sex, which was temporarily deemed “impure”.

(Even further off-topic, that incident was a classic example of how the membership can effectively push back. The pushback was sufficiently overwhelming that the interpretation was quickly rescinded. But it left no public record, so that people today, if they’re aware of it at all, can dismiss the whole incident as a rumor. But some of us, myself included, sat for recommend interviews during that period and know that it really happened. But that was before the internet, when it was possible to express an opinion without creating a public record.)

The context you’re leaving out is two words: marital rape. I don’t see anything remotely humorous about that.

Only the person who has gone through a severe trauma can really decide the best way to process it. Laughing at someone else’s trauma falls under the category of using humor to injure.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that humor is mandatory for all situations (good grief). I’m arguing it is not inherently wrong to view, process life through humor because life isn’t solely deadly and serious.

The loud laughter clause was always strange. Given that we had to talk around it, because we obviously weren’t following it, we’re strange. It’s good that it’s gone.